Introduction

India’s Northeast is a region rooted more in accident of geography than in shared bonds of history, culture and tradition. The region has over the centuries seen an extraordinary mixing of different races, cultures, languages and religions, leading to a diversity rarely seen elsewhere in India. With an area of about 2.6 lakh sq. kms., and population of little over 39 million, seven states of Northeast comprising of Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Tripura, and Sikkim is a conglomeration of around 475 ethnic groups and sub-groups speaking over 400 languages / dialects. The region accounts for around 8 per cent of India’s total geographical area and little less than 4 per cent of India’s total population. Of 635 communities listed in India as Tribal, more than 200 are in Northeast. Of 325 languages listed by ‘People of India’ project, 175 belonging to Tibeto – Burman group are spoken in Northeast (Bhaumik, 2009).

Political dynamics in post independent Northeast India is particularly characterised by numerous identity assertions articulated by educated elite and emerging middle class in a manner somewhat unconventional in nature but largely drawing vitality and strength from mass mobilisation in defence of political aspirations held to be sine qua non for preservation of ethnic and cultural distinctiveness (Deb, 2015). The means adopted for political articulation has been both constitutional and non-constitutional in nature which confronted the state, encompassing greater part of Northeast, which is homeland of numerous ethnic groups.

Northeast is home of many autochthonous tribes who have lived on clan loyalties and in glorious isolation from each other in time and clime, the region is not a melting pot of a pan-tribal society, but a veritable remake of Tower of Babel with tribes speaking different tongues, expressing different thoughts, following different faiths and practices. Often, they are at war with each other over supremacy or for preserving their identities from the assimilative advances of outsiders making the region a hotbed of political irreconcilabilities (Moorshahsry. 2015).

Alienation of ethnic groups and communities from mainstream India provided the springboard for a spurt of regional sentiments manifesting ultimately in insurgency, secessionist movements, outbursts, clashes, violence. The growth of militant, extremist groups sounds a discordant note in an environment surcharged with promotion of straight jacket mechanism in form of Sixth Schedule to the Constitution of India, by attempted political solution, without consent of people (Deb, 2015).

The problem of Northeast people in broader frame is (1) among themselves (2) with rest of India. All conflicts and clashes, contradictions and confrontations – be it the demand for sovereignty or separate statehood, special status for linguistic or cultural distinctiveness, sixth schedule status forth from these two main roots (Moorshahsry. 2015).

India’s Northeast emerged in British colonial discourse as a frontier region, initially connoting long swathe of mountains, jungles and riverine, marshy flatlands located between eastern limits of British-ruled Bengal and Kingdom of Ava (Burma). For purpose of expansion, commercial gain and border management, the British decided to explore the area immediately after historic Treaty of Yandabo in 1826. A senior official, R.B. Pemberton was asked to write the report on races and tribes of Bengal’s eastern border. In 1835, Pemberton wrote a survey of the area titled The Eastern Frontier of Bengal. In 1866, Alexander Mackenzie took charge of political correspondence in government of British Bengal. Mackenzie wrote comprehensive account of relations between British government and Hill tribes on eastern frontier of Bengal. Mackenzie completed his report in 1871 and titled it Memorandum on the Northeastern Frontier of Bengal. A revised and updated version was published in 1882 as History of the Relations of the Government with the Hill tribes of the Northeastern Frontier of Bengal. It took more than 30 years for ‘East’ to become ‘Northeast’ (Bhaumik, 2009).

The Northeast Frontier is term used sometimes to denote a boundary line and sometimes more generally to describe a tract. In latter sense, it embraces the whole of hill ranges Northeast and South of Assam Valley as well as western slopes of great mountain system lying between Bengal and independent Burma (Mackenzie, 1884).

J.C. Arbuthnott, British Commissioner of hill districts advocated extension of control over tribal areas (Arbuthnott, 1907). Mackenzie also stated that British should stand forth as governors and advisers for each tribe or people in the land (Bhaumik, 2009). This was perhaps done by British to justify their incursions in hill country east of undivided Bengal (Jafa, 1999).

Hill Tribes of Northeast India

Northeast India comprises the former British province of Assam and part or all of former princely states of Manipur, Tripura and Sikkim. There are areas of plains in modern State of Assam, but otherwise the region is mostly hilly or mountainous. The hills have long been populated with Tibeto – Burman (a branch of Sino – Tibetan) hill people, some of whom originate in other parts of Himalayas or of Southeast Asia. There are many distinct groups with unique languages, dress, cuisine and culture.

The British made little effort to integrate hill people into British India but governed through a system of village chiefs and headmen. They gave these leaders greater authority than they had traditionally enjoyed. The British enhanced power of village chiefs by giving them responsibility for administration, policing and justice. Where there was no chief, British created a "headman". The chiefs and headmen were subordinate to District Officer, arbitrator and supreme authority in any dispute (Chaube, 1975).

In 1873, ‘Inner Line Regulations’ were promulgated, marking extent of revenue administration beyond which tribal people were left to manage their own affairs subject to good behavior. No British subject or foreigner was permitted to cross ‘Inner Line’ without permission and rules were laid down for trade and acquisition of lands beyond (Bhaumik, 2009). The ‘inner line’ was expected to enact sharp split between contending world of capital and pre-capital, of modern and primitive (Kar, 2009). “The Inner Line became a frontier within a frontier adding to seclusion of hills and enhancing cultural and political distance between them and plains” (Verghese, 2004). The British were satisfied with token acceptance of suzerainty from tribes living beyond ‘Inner Line’ and did little to develop their economies (Bhaumik, 2009).

The British divided hill areas into two groups. In ‘Excluded Areas’, where tax collection was very difficult and tribal people were considered hostile, trade by plains people was not allowed. These were North-East Frontier Tracts, Naga Hills, Lushai Hills, and North Cachar Hills. Trade was allowed subject to some restrictions in less rugged ‘Partially Excluded Areas’ to south and west of Assam. These included Garo, Mikir, Khasi and Jantia Hills (Kumar, 2005).

The segregation enforced by British made hill tribes view plains people as exploiters, and to identify with their fellow hills people, while plains people saw hill tribes as backward people who were retarding development in the plains (Kumar, 2005).

The separation of Burma in 1937 and partition of British India in 1947 divided many tribal groups such as the Garo, Khasi, Kom, Mara, Kuki, Zomi, Mizo and Naga across international borders. State and district boundaries create multi-ethnic political entities, while further dividing tribal groups (Chaube, 1975).

Writing about broader area of mountainous parts of Southeast Asia that he calls “Zomia”, Professor James C. Scott argues in The Art of Not Being Governed (2009) that while valley people see hill people as backward, "our living ancestors", they may be better understood as "runaway, fugitive, maroon communities who have, over the course of two millennia, been fleeing the oppressions of state-making projects in the valleys" (Scott, 2009). Scott describes hill people as "self-governing" in contrast with “state-governed" people of the valleys. This anarchist culture is rapidly disappearing as hill people, their land and resources are integrated into nation states (Karlsson, 2013).

According to 2001 Census of India there were over 38 million people in Northeast India, with over 160 Scheduled Tribes as listed in the Sixth Schedule of the Indian Constitution, as well as a diverse population of non-tribal people. The Sixth Schedule gives a simplified view, since there are at least 475 ethnic groups speaking almost 400 languages or dialects (Kalita, 2011). The boundaries between hill tribes are not rigid, since there are clans that are common to several tribes, and conversion from one tribe to another is possible (Barkataki-Ruscheweyh and Lauser, 2013).

The British let Christian Church, mostly Protestant, undertake most welfare works (Chaube, 1975). Missionaries introduced Bibles translated into local languages and printed in Latin script. They had less success with Khasi and Jaintia people, who had closer trading and cultural connections with plains people. The missionaries were also unable to penetrate into what is now Arunachal Pradesh, where people retained their Buddhist or indigenous beliefs (Kumar, 2005). In some areas, Protestant missionaries converted people to Christianity and helped create educated elite with modern outlook who challenged the authority of chiefs and district administration. This elite pushed for greater autonomy for hill people within state of Assam and by 1930 this elite was starting to call for constitutional reform and obtained some autonomy at district level after Indian independence in 1947 (Chaube. 1975). In response to attempts by Assamese majority in plains to impose their language, hill people began to struggle for yet more autonomy as separate states within the Indian Union, which they largely achieved. Today, hill people have political control in most of new hill states surrounding Assam, although plains people control parts of the economy. There are continued tensions between hill people and plains people, and also tensions between different hill peoples in each hill state.

Manipur

Manipur is situated in extreme northeastern part of India, bordering Myanmar for about 352 kilometers in East and South of it; Nagaland to the north, Assam to the west and Mizoram to the south. About 90% of the area is mountainous, surrounding the central valley sloping to the south. Forests, mostly open, cover 77.4% of Manipur. It covers an area of 22327 sq. km (8,621 sq mi). Manipur has a population of 2,855,794 as per 2011 census. Of this total, 57.2% live in valley districts and remaining 42.8% in hill districts. The valley is mainly inhabited by Meitei speaking population. The hills are inhabited mainly by several ethno-linguistically diverse tribes belonging to Nagas, Kukis and smaller tribal groupings. Naga and Kuki settlements are also found in valley region, though less in numbers. There are also sizable population of Nepalis, Bengalis, Tamils and Marwaris living in Manipur. It also borders two regions of Myanmar, Sagaing Region to east and Chin State to south. Manipur is divided into 16 districts and has 34 recognized Scheduled Tribes and 3 non- tribal groups, belonging to different ethno - linguistic traits. The ethnic groups can be broadly classified into three catgegories: Metei, Naga and Kuki – Mizo. All of them belong to Mongoloid stock of race and Tibeto – Burman language family but varied from one another. Meiteis are concentrated in the valley and are the dominant population group in Manipur. Naga and Chin- Kuki – Mizo groups inhabit hill areas surrounding plains of Manipur (Thangboi Zou, 2015).

Main Reglions practiced by Ethnic Groups in Manipur

According to 2011 census, Manipur's ethnic groups practice variety of religions. Hinduism and Christianity are major religions of Manipur (Census of India, 2011).

Hinduism

Meitei ethnicity is majority group following Hinduism in Manipur, beside other minor immigrants following same faith in Manipur. Among indigenous communities of Manipur, Meiteis are the only Hindus as no other indigenous ethnic groups follow this faith. According to 2011 Census of India, about 41.39% of Manipuri people practice Hinduism. The Hindu population is heavily concentrated in Meitei dominant areas of Manipur Valley, among Meitei people. The districts of Bishnupur, Thoubal, Imphal East, and Imphal West all have Hindu majorities, averaging 67.62% (range 62.27–74.81%) according to 2011 census data.

Christianity

Christianity is religion of 41% of people in Manipur, but is majority in rural areas with 53%, and is predominant in hills. Christianity was brought by Protestant missionaries to Manipur in 19th century. In 20th century, few Christian schools were established, which introduced Western-type education. Christianity is predominant religion among Manipur tribals and tribal Christians make up vast majority (over 96%) of Christian population in Manipur.

History of Manipur

Sir James Johnstone, a colonial administrator during British era wrote in his 1896 book, My Experiences in Manipur and Naga Hills that “the early history of Manipur is lost in obscurity but there can be no doubt that it has existed as an independent kingdom from a very early period” (Singh, 2009). But much is recorded in the Chaithariol Kumbha, Manipur’s Royal Chronicles – In 13th Century, Chinese invaded this ancient kingdom. In 17th century, they again tried but failed. But Manipuri kings were also conquerors (Linter, 2015). The British were also desperate to check Burmese expansion. The first Anglo-Burmese war led to expulsion of Burmese army from Assam and Manipur. The Treaty of Yandabo in 1826 restored kingdom of Manipur to its Maharaja and Burmese were eased out of Manipur. The kingdom of Manipur was left alone, as long as it paid tribute. A British political resident was stationed in Manipur to ensure suzerainty and monitor any political activity considered detrimental to British interests (Bhaumik, 2009).

The Kingdom of Manipur was conquered by Great Britain following the brief Anglo – Manipur War of 1891, becoming a British protectorate. The British designated Manipur a ‘subordinate native state’ in 1891 and in 1907 stated that hill people were dependent on Maharaja of Manipur (Kumar, 2005). Prior to annexation on 15th October 1949 with India, Manipur was an independent Princely state ruled by Maharaja. Their boundary extended upto Kabaw valley in Myanmar. Manipur was scene of Kuki Rebellion 1917–1919 in which Kukis in the hills conducted guerrilla war against the British, and only yielded when British threatened to completely destroy their settlements (Kipgen, n.d.). Between 1917 and 1939, some people of Manipur pressed princely rulers for democracy. By late 1930s, princely state of Manipur negotiated with British administration its preference to continue to be part of Indian Empire, rather than part of Burma, which was being separated from India. These negotiations were cut short with the outbreak of World War II in 1939. At the time of Indian Independence from British Rule in 1947, Northeastern region consisted of Assam and princely states of Manipur and Tripura. Manipur and Tripura became Union Territories of India in 1956 and states in 1972. Hijam Irabot Singh (1896–1951) opposed merger of Manipur with India and proposed creation of Purbanchal republic that would comprise Manipur, Tripura, Cachar and Mizo hills. It would also include Kabaw Valley, which had been ceded to Burma (Kalita, 2011). After the war, British India moved towards independence and princely states which had existed alongside it became responsible for their own external affairs and defence, unless they joined new India or new Pakistan. The Manipur State Constitution Act of 1947 established a democratic form of government, with the Maharaja continuing as the head of state. Maharaja Budhchandra was summoned to Shillong, to merge the kingdom into the Union of India. Later, on 21st September 1949, he signed a Merger Agreement, merging the kingdom into India, which led to its becoming a Part C State (Singh, 2003; Dikshit and Dikshit, 2013). This merger was later disputed by groups in Manipur, as having been completed without consensus and under duress. (Kannabiran and Singh, 2008). Thereafter, the legislative assembly was dissolved, On 15th October 1949 Manipur became part of the Indian Union as a part "C" State (IMPHAL, 2017) It became a Union Territory in 1956 (Rajgopalan, 2008). In 1972 Manipur became a full state by the North – Eastern Areas (Reorganisation) Act, 1971. (IMPHAL, 2017). Manipur was not included in the Eighth Schedule until 1992 (Rajgopalan, 2008). In 1947, Manipur adopted a constitution that provided for universal adult suffrage and placed limitations on the king's power. Also in 1947, the king signed an Instrument of Accession with India, to take effect in 1949 possibly exceeding his authority under the constitution (Rajgopalan, 2008).

As a result of British fallacious policy, hill area was administered by British political agent and valley was allowed to rule by Meitei king. British also rehabilitated Kuki before the Naga with intention to fight against Burmese, Lushai and Naga tribes. Manipur had first experience of Hmar – Kuki conflict (1959 -60) for regrouping the hill tribes as ‘Kuki’ or ‘Naga’. Since then, last decade erupted with Naga – Kuki, Kuki – Paite and Kuki – Metei intra community conflict. The Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act of 1958 (AFSPA) was enacted to tackle insurgency in ‘disturbed areas’ of northeast. It gives the army the right to open fire “against any person who is acting in contravention of any law or order for the time being in force in the disturbed area prohibiting the assembly of five or more persons”. The law was supposed to be in force for only a year, but Naga struggle continued. Then came Mizo rebellion,unrest in Manipur and other areas in North East, The law was never revoked and now applies to any ‘disturbed area’ in Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland and Tripura. The whole of Manipur was declared a ‘disturbed area’ in 1980. The designation ‘disturbed area’ has been lifted only in certain parts of Imphal municipality (Linter, 2015).

Ethnic Groups and Civil Strife in Manipur

Decades of civil strife have torn entire Manipur apart. The majority or 57 per cent of the population of Manipur is predominantly Hindu Meitei and dominates central lowlands, while various Naga tribes in surrounding hills make up 13 – 14 per cent and Kukis, another 12 -13 per cent. There are also number of smaller ethnic groups in Manipur, such as Mizo / Chin and Paite – related tribes in Churachandpur; Muslim Meitei Pangal in Imphal Valley, Bishnupur, Thoubal and Chandel; Komren in Senapati; and even sizable population of Nepalese and ‘mainstream’ Indians in Imphal and town of Moreh on Myanmar border. Meiteis as well as Nagas, Kukis and other tribals all speak tongues that belong to Tibeto – Burman family of languages (Linter, 2015).

Most of the rebel groups, which claim to represent one ethnic group or other, collect ‘taxes’ from businesses and individuals. Armed forces and paramilitary forces patrol Imphal. The security forces act with impunity, while extortion by rebels and corruption within local administration hinders any serious development efforts. Money sent by central government tends to disappear into pockets of local officials. Manipur provides an extreme example of how a civilian population can be sqeezed between security forces and ruthless rebels. The outcome of all this is a sad state of affairs in Manipur, which is far worse off than any of other northeastern states. Here, there are more insurgent groups than in any other northeastern Indian state, fighting the government forces as well as each other. Many of the groups have also become criminisalised and carry out extortions in name of “Manipuri nationalism” (Linter, 2015). It is not known exactly how much Manipur’s ‘revolutionaries’ collect in ‘taxes’ but research done by Rakhee Bhattacharya in her 2011 study Development Disparities in Northeast India argues convincingly that economic development in resource- rich northeastern India has been arrested owning to many complex issues, including illegal economy of insurgency. In Manipur, pay- off has to be made not to one but to several insurgent groups. Considering extent of extortion, it is hardly surprising that Manipur has remained highly underdeveloped. While insurgents collect “taxes” all over the northeast, the multitude of rebel groups in Manipur has made the situation there much worse than elsewhere in the region (Bhattacharya, 2011). Romesh Bhattacharji, a former commissioner of custom in Assam wrote “You can smell fear and feel the wariness. The Kukis and Nagas are fighting each other. The Meiteis, the Nagas, and the Kukis are all against the authority…. Here yesterday’s headline will be repeated tomorrow. They tell the same story. Ambush, massacre, abduction, extortion, raid and retaliatory raid, rape. …The list is endless” (Bhattacharji, 2002). “Manipur’s saga is …. a reflection of what is perhaps the world’s most complex and longest – running web of ethnic insurgencies” (Misra and Pandita, 2010).

In 2005 about 34.41% of the population were members of scheduled tribes (Kumar, 2005). The hill tribes of Manipur included Naga tribes in areas next to Nagaland, and Kuki and Mizo tribes in areas next to Mizoram. The umbrella terms “Naga" and "Kuki" in the first list of schedule tribes were not accepted by the tribes, who insisted on a change to the list in 1965 under which they were designated by their names. Only the Thadou tribe retained the Kuki name (Kumar, 2005). Meiteis are majority ethnic group in Manipur, but occupied only a tenth of land and were not allowed to buy land in hill areas. Metei people represent around 53% of population of Manipur state, followed by various Naga ethnic groups at 24% and various Kuki / Zomi tribes (also known as Chin-Kuki-Mizo people) at 16% (Lisam, n.d.). By contrast, hill tribes could buy land, and as scheduled tribes had better opportunities for employment in public sector.

Meiteis responded by reviving their traditional culture and religion, protesting the presence and special powers of armed forces in the area, and forming militant separatist groups with links to other such groups in Myanmar and Northeast India (Kalita, 2011). These included United National Liberation Front, Peoples Liberation Army and Peoples Revolutionary Party of Kangleipak, and fought an urban or semi-urban guerrilla war in Imphal valley (Kalita, 2011).

Land and Development Crunch

One of Manipur’s chief problems has been the severe shortage of land in the valley and development neglect of hill areas. Manipur constitutes a fertile bowl-shaped valley surrounded by hills. While the lush Manipur valley holds only ten per cent (2000 sq. km) of the state land, it is home to 70 per cent of the population, primarily the Meitei. The hill areas comprise 90 per cent of the State’s territory, occupied by Naga and Kuki communities, along with some other small tribal groups, who make up 30 per cent of State’s population. They have been protected by special laws that ensure tribal customary rights and prevention of land transfer to the non-tribal (Chinai, 2018).

The kingdom of Manipur came under British protectorate after the treaty of Yandaboo, 1826, that concluded the Burmese occupation of Assam and Manipur. The hills of Manipur, held to be non-revenue generating areas, were generally left unadministered and were under the President, Manipur State Durbar, who was a British Indian Civil Services officer. The valley was under regular modern revenue administration (Phanjoubam, 2016). Following independence, this tradition continued and in 1960, when Manipur was still a Union Territory, the Manipur Land Revenue and Land Reforms Act was introduced in the valley. The non tax - paying hills were still left largely un-administered. In 1972 when Manipur became a full – fledged state, this divide between valley and hills was formalized through application of article 371 – C in hill areas. This provision of the Constitution of India pertains to protecting the culture, custom and land of tribal people (Chinai, 2018).

Sections of Manipur’s hill tribes have raised apprehensions that the State Government is seeking to curtail their protection against land transfers through amendments to MLR & LR 7th Amendment Bill, 2015 and protection of Manipur People’s Bill 2015. They held that lacking access to fertile, agricultural land such transfer would jeopardise their means of survival. Hill tribal societies say that they have been neglected and suffer under-development from successive Manipur governments. Autonomous District Councils (ADCs) were created in 1973 under Manipur (Hill Area) Autonomous District Councils Act 1971 of Government of Manipur. All hill area matters are required to be referred to Hill Area Committee, which is a Mini assembly of all 20 hill MLAs within the 60 member Manipur State Legislative Assembly. Since 2014 there has been a demand to upgrade to Sixth Schedule of the Indian Constitution, as applicable to Meghalaya, Mizoram, Tripura and Assam which would bring greater autonomy. The Sixth Schedule of the Constitution of India provides for tribal areas in Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura and Mizoram to be administered as autonomous districts or regions. The Fifth Schedule applies to scheduled areas in other parts of India. Neither schedule applies to the hill areas of Manipur, where all people are tribal, or to tribes of Assam plains. The valley has no safeguards against legal land transfers and over the years it has led to acute paucity of living and survival space for the Meitei, who are primarily agricultural people. The Meitei have been demanding protective laws against transfer of their land, placement of controls on presence of non- locals through implementation of Inner Line Permit (ILP), which is presently applicable in Nagaland, Mizoram and Arunachal, which is issued under the Bengal Eastern Frontier Regulation, 1873. The Meitei are also seeking the status of scheduled tribes so that they can also avail reservation facilities in education, jobs and gain access to land in the hill tribal areas (Chinai, 2018).

Faced with simultaneous uprisings in plains and by Kukis of hill regions, in 2008 Indian Army signed a Suspension of Operation agreement with eight Kuki groups in the hope that they could be used against rebel groups in the valley. Active groups in Manipur in 2009 included People's Revolutionary Party of Kangleipak, Military Council faction of Kangleipak Communist Party, People's United Liberation Front, People's Liberation Army and Kuki Revolutionary Army. The areas bordering Nagaland were affected by National Socialist Council of Nagaland-Isak-Muivah (NSCN-IM) (Kalita, 2011).

Manipur in post – India’s independence saw great deal of political consciousness in face of ethnic revival among different tribes of Naga and Chin – Kuki – Mizo group. Extremism in Manipur can generally be categorised into three streams: the valley (Meitei) stream who believed that the Manipur king was forced to access into the Indian union and who are fighting for sovereignty; the Naga stream, who has been fighting for integration of all Naga inhabited areas in Assam, Nagaland, Manipur and Arunachal Pradesh; and third stream is Chin – Kuki – Mizo or Zo Group who has risen up to claim for their ethnic autonomous ‘homeland’ within Manipur and across international border to Burma. This form of ethno – nationalist movement with certain degree of patronage, moral and material support from people of each ethnic group has given rise to militancy in Manipur (Thangboi Zou, 2015).

Manipur gave birth to People’s Liberation Army (PLA) in 1978 adopting the violent way for complete independence. After PLA, a dozen of insurgent outfits emerged with demand for regional autonomy to secession or total independence and have been operating in Manipur. The noted among them are Revolutionary People’s Front (RPF), United Liberation Front (UNLF) in 1986, People’s Revolution Party of Kangleipak (PREPAK) a valley based Meitei insurgent group who claimed an independent state embracing geographically all North East states except western part of Assam and a part of Tripura. Kangleipak Communist Party (KCP). Hmar People’s Convention (HPC), Kuki National Organisation (KNO), Kuki National Army (KNA) are the other outfits of Manipur. The KNA demanded autonomous state near the Myanmaar for Kukis while other claimed ‘Kuki-homeland’ covering Ukrul, Senapati, Imphal and Kuki dominated areas of Nagaland, Assam and Manipur with 22.32 sq.km geographical areas having nine districts and thirty three recognized scheduled tribes. The five hill districts Chandel, Churachandpur, Tamenlong, Senapati and Ukhrul dominated by Tribal and the state land laws prohibited the Meitei (the largest community) and non tribal to buy land and settle in the hills. The four valley districts (2.23 sq. km.) – Imphal East, Imphal West, Bishnupur and Thoubal are a mixture of more or less all tribe representatives.

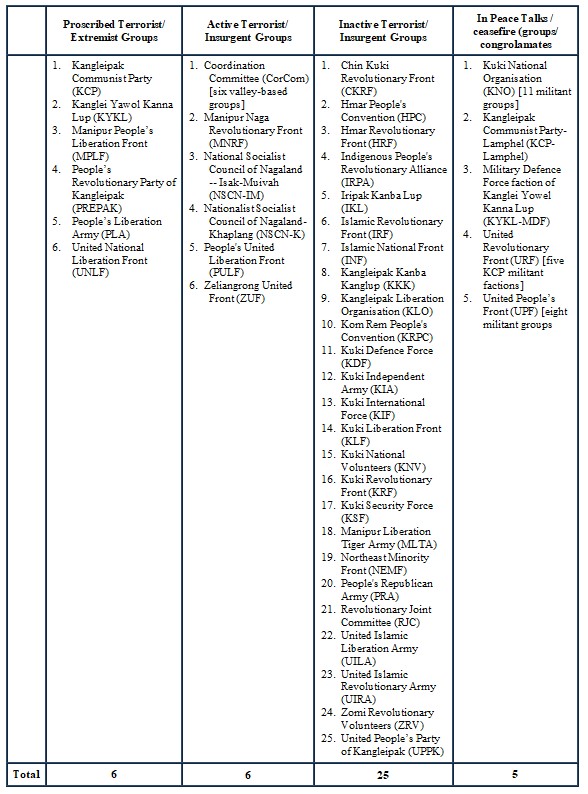

Splinter groups have arisen within some of the armed groups, and disagreement between them is rife. Other than UNLF, PLA, and PREPAK, Manipuri insurgent groups include Revolutionary Peoples Front (RPF), Manipur Liberation Front Army (MLFA), Kanglei Yawol Kanba Lup (KYKL), Revolutionary Joint Committee (RJC), Kangleipak Communist Party (KCP), Peoples United Liberation Front (PULF), Manipur Naga People Front (MNPF), National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN-K), National Socialist Council of Nagaland (NSCN-I/M), United Kuki Liberation Front (UKLF), Kuki National Front (KNF), Kuki National Army (KNA), Kuki Defence Force (KDF), Kuki Democratic Movement (KDM), Kuki National Organisation (KNO), Kuki Security Force (KSF), Chin Kuki Revolutionary Front (CKRF), Kom Rem Peoples Convention (KRPC), Zomi Revolutionary Volunteers (ZRV), Zomi Revolutionary Army (ZRA), Zomi Reunification Organisation (ZRO), and Hmar Peoples Convention (HPC).

The Meitei insurgent groups seek independence from India. The Kuki insurgent groups want separate state for Kukis to be carved out from present state of Manipur. Kuki insurgent groups are under two umbrella organisations: Kuki National Organisation (KNO) and United Peoples Forum. The Nagas wish to annex part of Manipur and merge with greater Nagaland or Nagalim, which is in conflict with Meitei insurgent demands for integrity of their vision of an independent state. There have been many tensions between the tribes and numerous clashes between Naga and Kukis, Meiteis and Muslims.

Manipur had a long record of insurgency and inter-ethnic violence. The first armed opposition group in Manipur, United National Liberation Front (UNLF), was founded in 1964 and declared that it wanted to gain independence from India and form Manipur as a new country. Over time, many more groups formed in Manipur, each with different goals, and deriving support from diverse ethnic groups in Manipur. In 1977, People’s Revolutionary Party of Kangleipak (PREPAK) was formed, and People's Liberation Army (PLA), formed in 1978 which Human Rights Watch said had received arms and training from China. In 1980, Kangleipak Communist Party (KCP) was formed. These groups began a spree of bank robberies and attacks on police officers and government buildings. The state government appealed to the central government in New Delhi for support in combating this violence.

Insurgency in Manipur (Illustrative list of events)

The following is an illustrative list of events relating to the insurgency in Manipur.

• 4th July 2000, 18 insurgents surrendered to authorities of Imphal in presence of Manipur Chief Minister Nipamacha Singh.

• 18th September 2001, Indian military killed 5 PLA members during shootout in Khoupum valley, Tamenglong district.

• 10th February 2003, KYKL ambush leads to death of 5 Border Security Force personnel, in Leingangtabi along Imphal-Moreh road.

• 16th January 2005, security forces uncovered a PLA camp in Theogtang Zoukanou, Churachandpur district. A total of 76 rifles, 20 small arms, and large amounts of ammunition were seized.

• 30th June 2005, 5 policemen and 4 PLA rebels were slain in a clash, in Thangjng Ching, Churachandpur district. A radio set, weapons, as well as documentation were confiscated from dead guerrillas.

• 17th August 2007, police arrested 12 rebels from official residences of three Members of the Legislative Assembly in Imphal.

• 30th November 2010, authorities detained UNLF chairman Rajkumar Meghen in Motihari, Bihar.

• 15th April 2011, a NSCN-IM ambush resulted in death of 8 people and injury of 6 others, the victims belonged to Manipur Legislative Assembly and the Manipur police. The incident took place in Riha, Yeingangpokpi 12 km from Imphal after the then MLA Wungnaoshang Keishing conference meeting, Ukhrul district.

• 1st August 2011, 5 people were killed and 8 others injured when National Socialist Council of Nagaland – Isak Muivah rebels detonated a bomb outside a barber shop in Sanghakpam Bazaar, Imphal.

• 30th April 2012, 103 rebels belonging to UNLF, PULF, KYKL, PREPAK, KNLF, KCP, PLA, UNPC, NSCN-IM, NSCN-K, UPPK and KRPA and KRF, surrendered before Chief Minister Ibobi Singh during a ceremony at Mantripukhri in the Imphal West District.

• 14th September 2013, an IED detonated in a tent housing migrant workers in city of Imphal, killing at least 9 and injuring 20 people.

• 20th February 2015, security forces conducted number of raids in areas of Wangjing and Khongtal, arresting 5 PREPAK cadres.

• 23th May 2015, security forces carried out joint operation in village of Hingojang, Senapati district. Three rebels were killed, and one was detained after rebels offered armed resistance.

• 4th June 2015, guerrillas ambushed a military convoy in Chandel district, killing 18 soldiers and wounding 15 others. UNLFW claimed responsibility for the attack.

• 9th June 2015, operators of 21st Para SF Battalion of Indian army carried out cross border operation into Myanmar, which resulted in death of approximately 20 rebels including those who attacked an army convoy on 4th June 2015. Commandos went few kilometers inside Myanmar territory to destroy two camps of insurgents hiding there after their attacks in Manipur and Arunachal Pradesh on 4th June 2015 by NSCN (K) and KYKL outfits.

• 22nd May 2016, rebels ambushed and killed six Indian paramilitary soldiers in Manipur, India near the northeastern region bordering Myanmar.

• 13th November 2021, rebels ambushed a convoy belonging to Assam Rifles, killing five Indian soldiers and two civilians in Churachandpur district, Manipur. The deceased also included an Indian army colonel and his family. Indian police suspect that rebels belonging to People’s Liberation Army of Manipur (PLA) were responsible for the ambush.

Understanding Violence and Conflict between Meitei and Kuki in Manipur in 2023

Manipur, like rest of northeastern region, consists of variety of communities that have a history of mistrust towards one another. Meiteis make up slightly over half of the population, while tribal communities, consisting of Kukis and Nagas, make up nearly 40%, with Kukis making up 25% and Nagas 15%. Although Meiteis are predominantly Hindu, they also follow their ancient animist beliefs and practices, and there are Meitei Pangals who make up 8% of Meitei population and practice Islam. Meiteis are more educated and hold greater representation in business and politics in state compared to Kukis and Nagas. The dominant largely Hindu community, which is based in state’s capital city of Imphal, forms more than 50 percent of state’s population of 3.5 million, as per India’s census in 2011. While Meiteis are mostly based in plains, they have a presence in hills as well.

The majority of Kukis and Nagas follow Christian faith. The two mostly Christian tribes form around 40 percent of state’s population, and enjoy “Scheduled Tribe” status, which gives them land-ownership rights in hills and forests. They are most significant tribes residing in the hills. Kukis are dispersed throughout northeast region of India and Myanmar. In Manipur, many Kukis migrated from Myanmar several centuries ago and were initially settled by Meitei rulers in the hills to serve as barrier between Meiteis in Imphal valley and Nagas who frequently attacked the valley. Later, during insurgency in Nagaland, Naga rebels argued that Kukis were residing in areas that should be part of separate Naga state they were demanding. In 1993, there was intense violence between Nagas and Kukis in Manipur, resulting in deaths of over a hundred Kukis at hands of Nagas. Although Nagas and Kukis have historically been at odds with each other, they are in agreement in their opposition to Meiteis.

The violence erupted on 3rd May 2023, in India's state of Manipur. The violence killed around 98 people and injured around 310. It began in Churachandpur district during the "Tribal Solidarity March" called by All Tribal Student Union Manipur (ATSUM) to protest granting of reservations to majority Meitei community. The ‘Tribal Solidarity March’ resulted in violence in Torbung area of Churachandpur district. The march was organised by various tribes, including Nagas and Kukis, in response to demand for Scheduled Tribe (ST) status by Meitei community, which the Manipur High Court had instructed the state government to recommend to the Centre within four weeks. During the march, an armed mob allegedly attacked Meitei community members, sparking retaliatory attacks in valley districts, which then spread the violence throughout Manipur. The current conflict between Meiteis and 'tribals' is extension of hills-versus-plains conflict seen elsewhere in northeast. Recent Manipur violence stems from disputes over land and special privileges, which have created divisions between religious and ethnic communities in Manipur. The immediate provocation for ethnic unrest appears to have been the demand for Meitei community, which accounts for 53 per cent of Manipur's population and primarily inhabits Manipur Valley, to be included in the Scheduled Tribe list.

The Meiteis claim they are marginalized as compared to other mainstream communities. The tribes believe granting “Scheduled Tribe” status to Meiteis would be an infringement of their rights as they claim to be marginalized part of the population and not the Meiteis. The tribes believe Meiteis are already a dominant community and call the shots in the state politics and hence should not be given affirmative action. They see the Scheduled Tribe status as Meiteis eating into their pie. Tribal areas in the northeastern part of India enjoy certain constitutional protection and there is anxiety amongst them that scheduled tribe status would mean that Meiteis can own land in the hills.

In February 2023, state government began an eviction drive in districts of Churachandpur, Kangpokpi and Tengnoupal, declaring forest dwellers as encroachers which was seen as anti-tribal. The government’s eviction of Kuki villages, which were encroaching on protected forest area, was another factor that contributed to already tense situation, and it provided further fuel to growing animosity against Meitei community. In March 2023, five people were injured in violent clash at Thomas Ground in Kangpokpi district where protesters gathered to hold a rally against "encroachment of tribal land in the name of reserved forests, protected forests and wildlife sanctuary". In the same month, Manipur Cabinet withdrew from Suspension of Operation ceasefire agreements with Kuki National Army and Zomi Revolutinary Army. On 11th April 2023, in Imphal’s Tribal Colony locality, three churches were razed for being "illegal constructions" on government land, which led to more discontent and further fed into animosities on both sides. On 20th April 2023, a single judge of the Manipur High Court directed the state government to "consider request of the Metei community to be included in the Scheduled Tribes (ST) list." The Kukis feared that the ST status would allow the Meiteis purchase land in the prohibited hilly areas. The Meiteis, who are largely Hindu and make 53% of the population, are prohibited from settling in hilly regions of the state as per Land Reform Act of Manipur, which limits them to reside in Imphal Valley, constituting 10% of state's land.

The Tribal population, consisting of Kukis and Nagas, which form about 40% of Manipur's 3.5 million people, reside in reserved and protected hilly regions consisting of rest of 90% of Manipur. The tribal population is not prohibited from settling in valley region. The Meitei people in Manipur suspect that there has been huge increase in tribal population in Manipur which "cannot be explained by natural birth". They have been requesting application of National Register of Citizens (NRC) in Manipur for identification of illegal immigration from Myanmar. The Kukis say that illegal immigration is a pretext under which Meitei population wants to drive tribal population from their lands. While Kukis dominate land ownership, Meiteis dominate political power in Manipur Legislative Assembly, where they control 40 out of 60 seats. The disputes over land and illegal immigration have been primary root of tensions which have existed for decades. Christianisation of tribal population of Manipur has contributed to socio-cultural gap amongst two groups in Manipur.

The Chief Minister of Manipur was scheduled to visit Churachandpur on 28th April 2023 and inaugurate an open gym. Before inauguration could take place, on 27th April 2023, the gym was set on fire by protestors. Section 144 of IPC was invoked for 5 days and police clashed with protestors on 28th April 2023. In Manipur, curfew was imposed across eight districts, including non-tribal dominated Imphal West, Kakching, Thoubal, Jiribam, and Bishnupur districts, as well as tribal-dominated Churachandpur, Kangpokpi, and Tengnoupal districts.

Amidst long-standing tensions between Meitei and Kuki people, Kuki organization called All Tribal Student Union Manipur (ATSUM), opposed to decision of the Manipur High Court, called for a march named "Tribal Solidarity March" on 3rd May 2023, which turned violent in district of Churachandpur. Reportedly, more than 60,000 protestors participated in this march. During the violence on 3rd May 2023, residence of mostly Kuki Tribal population was attacked in non-tribal areas. According to police, many houses of tribal population in Imphal were attacked and 500 occupants were displaced and had to take shelter in Lamphelpat. Around 1000 Meiteis affected by violence also had to flee from the region and take shelter in Bishnupur. Twenty houses were burnt in city of Kangpokpi. Violence was observed in Churachandpura, Kakching, Canchipur, Soibam Leikai, Tenugopal, Langol, Kangpokpi and Moreh while Meiteis mostly being concentrated in Imphal Valley during which several houses and other properties were burnt and destroyed.

On 4th May 2023, fresh cases of violence were reported. The police force had to fire several rounds of tear shells to control rioters. Kuki MLA who is representative of tribal headquarters of Churachandpur, was attacked during riots while he was returning from state secretariat. By the end of 3rd May 2023, 55 columns of the Assam Rifles and the Indian Army were deployed in the region and by 4th May 2023, more than 9,000 people were relocated to safer locations. By 5th May 2023, about 20,000 and by 6th May 2023, 23,000 people had been relocated to safe locations under military supervision. The central government airlifted 5 companies of Rapid Action Force to the region and 10,000 army, para-military forces and Central Armed Police Forces were deployed in Manipur.

On 4th May 2023, the Union government invoked Article 355, the security provision of the Indian constitution, and took over the security situation of Manipur. Several hill-based militants engaged with Indian Reserve Battalion in which five militants were killed. The army ‘significantly enhanced’ its surveillance in violence-affected areas, including Imphal Valley, through aerial means such as drones and deployment of military helicopters while curfew was relaxed for limited period from 7th May 2023.

The Road Ahead …

Although there were several recent factors that triggered protests, they ultimately arose from deep-seated divisions within the society, where different groups compete for benefits and rights. The Manipur violence is an ongoing ethnic clash between the Hindu Meitei and Christian tribal Kuki people. Around 23,000 people displaced from both sides, most of them sheltering in army camps, in ethnic violence in India’s northeastern state of Manipur. Meiteis are in minority in hills, so they have been displaced from there, while tribals are in minority in plains and cities, where they have been displaced from. Since outbreak of violent clashes, central government invoked an article of the constitution, Art. 355 that lets it take over and have special powers in a state. Both sides have a long history of violent clashes and deep running ethnic tensions. Violence has historically been ethnic and that while there may be some overlap with religion, it has mostly remained an ethnic conflict with some instances of inter-tribe violence as well. There have been deep-rooted long running tensions between the hill and the valley. There has been violence in Manipur since its incorporation into the Indian state. It is a complicated, complex region shaped by several factors.

If large scale displacement in conflict prone states like Manipur has to be avoided, the government must adopt certain measures at the policy level:

1. Land alienation in India’s Northeast has led to serious ethnic tensions. Land alienation has been at the root of the most horrible, headline gathering ethnic carnages that have shaken the region. Armed militiamen representing an ethnic group formed the core group that perpetrated the violence. Systematic incitement in an atmosphere already vitiated by agitations, insurgencies also occur. Tribesmen list perceived land loss to settlers as their main grievance, which leads to furious outburst of ethnic violence. In Manipur’s hill region, land alienation was growing until the Manipur Land Revenue and Reforms Act was passed in 1960. This act prohibited sale of tribal land to non-tribals. However, due to growing pressure in the Imphal Valley, Meiteis have also been losing land, not necessarily to outsiders but to their own wealthier kinsmen. This again has forced many landless peasants to migrate to towns. They again swelled ranks of rootless men and women, from whom insurgents draw their recruits as well as demand for ST status for Meiteis. Protection of indigenous land is imperative because land alienation is major source of ethnic conflict in Manipur.

2. Illegal migration from Myanmar, Bangladesh must be stopped. Any major inflow of population is likely to create ethnic or religious backlash.

3. Empowerment of indigenous populations should not prevent tough policy towards insurgents who resort to ethnic cleansing and violent militancy.

4. Ethnic conflicts in Northeast have led to considerable internal displacement of victim populations. Once displacement has taken place, it is important to provide security to affected population and organise their return to ancestral villages as soon as possible.

5. It needs to be figured out whether it is possible to change it into a vital bridgehead with Southeast Asia.

6. There is need to work out a multi-ethnic ethos in governance. No state can be totally homogenous in ethnic or religious terms and minorities are bound to persist.

7. One has to resolve the ethnic conflicts not by force but by key structural changes in its polity that would accommodate battling ethnicities.

8. Manipur needs an agenda of ethnic reconciliation as if ethnic conflicts intensify, drug-lords due to proximity to Myanmar will step in to take advantage of disturbed conditions.

9. Return of peace and imaginative planning can ensure turnaround for Manipur. The development of political culture of tolerance is needed in Manipur.

References

Arthbuttnott, J.C. (1907). Note from Camp Mauplong to Fort William. 26th September. Quoted in Suhas Chatterji (1985). Mizoram under British Rule. Delhi: Mittal Publications.

Barkataki-Ruscheweyh, M. and Lauser, A. (2013), Editors' Introduction: Performing Identity Politics and Culture in Northeast India and Beyond, Asian Ethnology, 72 (2), 189–197.

Bhattacharji, R. (2002 ). Lands of Early Dawn: Northeast of India. New Delhi: Rupa Publications.

Bhattacharya, R. (2011). Development Disparities in Northeast India. New Delhi: Foundation Books.

Bhaumik, S. (2009). Troubled Periphery – Crises of India’s North East. New Delhi: Sage Publications.

Census of India (2011). Census of India Website: Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India.

Chaube S.K. (1975). Interethnic Politics in Northeast India. International Review of Modern Sociology, 5 (2), 193–200.

Chinai, R. (2018). Understanding India’s Northeast – A Reporter’s Journal. Mumbai: Rupa Chinai.

Deb, B.J. (2015). Extremism in North East India. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd.

Jafa, V.S. (1999). Administrative Policies and Ethnic Disintegration: Engineering Conflicts in India’s North East. Faultlines, 2nd August 1999.

Kipgen, D.M. (n.d.). The Great Kuki Rebellion of 1917-19: Its Real Significances, (Courtesy: The Sangai Express).

Kumar, N. (2005). Identity Politics in the Hill Tribal Communities in the North-Eastern India, Sociological Bulletin Society, 54 (2),195–217.

Lisam, K.S. (n.d.) Encyclopaedia of Manipur, pp. 322–347.

Linter, B. (2015). Great Game East: India, China and the Struggle for Asia’s Most Volatile Frontier. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Misra, N. and Pandita, R. (2010). The Absent State: Insurgency as an Excuse for Misgovernance. Gurgaon: Hachette India.

Moorshahsry. R.S. (2015). North East India: Maladies and Remedies. In B.J. Deb (Ed.), Extremism in North East India, New Delhi: Concept Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd., pp. 1 – 5.

Thangboi Zou, S. (2015). Wave of Ethnic Revival and Extremism among Chin - Kuki – Mizo (Zo) People in Manipur. In B.J. Deb (Ed.), Extremism in North East India, New Delhi: Concept Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd., pp. 258 – 280.

Kalita, N. (2011). Resolving Ethnic Conflict in Northeast India. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Indian History Congress, 72, PART–II: 1354–136.

Kannabiran, K. and Singh, R. (2008). Challenging the Rules(s) of Law. New Delhi: SAGE Publications.

Kar, B. (2009). When was the Postcolonial? A History of Policing Impossible Lines. In Sanjib Baruah (Ed.) Beyond Counter-Insurgency: Breaking the Impasse in Northeast India. Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Karlsson B. G. (2013). Evading the State: Ethnicity in Northeast India through the Lens of James Scott. Asian Ethnology, 72 (2), 321–331.

Mackenzie, A. (1884). Memorandum on the Northeastern Frontier of Bengal. Calcutta: Government of India Press.

Mackenzie, A. (2001). (republished). The North East Frontier of India. Delhi: Mittal Publications.

Manipur (IMPHAL), knowindia.gov.in

Phanjoubam, P. (2016). The Northeast Question: Conflicts and Frontiers. London: Routledge.

Rajagopalan, S. (2008). Reading Maps, Seeking Directions, Report Title: Peace Accords in Northeast India:

Scott, J. C. (2009). The Art of Not being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. Yale University Press.

Singh, K.S. (1998). People of India, Vol. 31, Manipur. Calcutta : Anthropological Survey of India.

Singh, T. Hemo, (2009). Manipur Imbroglio. New Delhi: Akansha Publishing House.

Singh, N. J. (2005). Revolutionary Movements in Manipur. New Delhi: Akansha Publishing House.

Singh, U.B. (2003). India Fiscal Federalism in Indian Union,

Verghese, B.G. (2004). India’s Northeast Resurgent: Ethnicity, Insurgency, Governance, Development. Delhi: Konark Publishers.