Background:

India delivered the Brahmos missiles to the Philippines on 19 April 2024. This delivery comes two years after India signed a 375$ million contracts with the Philippines government for the delivery of 3 Brahmos missile systems (coastal variants) to defend its territorial sovereignty, especially against the Chinese aggression in the West Philippines sea. Since the Philippines will be the first operator in the ASEAN region to operate these state-of-the-art missile systems, it is now important to understand and estimate the implications of this export to protect Philippines territorial integrity against Chinese aggression. The Brahmos missiles which have been delivered to the Philippines are of the anti-ship variant.1 Therefore, this article will try to estimate the change in balance of power in ASEAN region due to this development and also to understand the associated deterrence capability.

Deterrence for Philippines:

Deterrence in military context can be defined as the ‘threat of force to discourage someone from doing something unwanted.’ As per NATO Review, this can be achieved through the threat of retaliation (deterrence by punishment) or by denying the opponent’s war aims (deterrence by denial). A factor in achieving deterrence has been an element of surprise. But sometimes military superiority has not ensured deterrence. One of the most important features is credibility. The other important aspect deals with protecting one’s national interests. For some countries the security of its treaty allies is a vital national interest.2 According to Henry Kissinger, deterrence is a mix of power, the will to use it and the assessment of it by the potential adversary. Deterrence is meaningful if only these factors are used as a product and not as a sum. If anyone, of them is absent, the deterrence fails which is a limitation. They have various forms like nuclear deterrence, conventional deterrence, escalated deterrence, extended deterrence, maximum and minimum deterrence, etc.3 The US has developed the concept of joint deterrence since 2006 to assure its allies and treaty partners. The deterrence of an adversary depends on its costs, benefits and consequences. In this regard, it plans to deny benefits, impose costs and encourage restraint on its adversaries. Deterrence challenges depend on a vast array of factors like potential adversaries, uncertainty, etc. So, to tackle different adversaries, the US concept of joint deterrence would incorporate different means like global situational awareness, command and control, security cooperation and military integration, force projection, active and passive defences etc which are expected to continue through the year 2025.4

From the Philippines perspective, due to the rising Chinese aggression in the West Philippines Sea (WPS) region, they decided to come out with a new National Security Policy (NSP) in 2023 with a changed attitude towards China. After their arbitration victory in PCA in 2016 which rejected most of China’s claims in the WPS, they are now more determined to protect their national security interests. The NSP states that the Philippines government shall ensure the inviolability of its national sovereignty and territorial integrity on land, sea, air, space and cyberspace by building a strong deterrence. For this purpose, they are committed to strengthen military relations with other states, including India to harness a collective deterrence against potential existential threat to their sovereign spaces. This ‘strong deterrence’ can be understood to be equivalent to the Japanese counter strike capability.5 In 2022, when the Brahmos deal was signed, the then Defense Secretary Delfin N. Lorenzana had stated that “Equipping our Navy with this vital asset is imperative as the Philippines continues to protect the integrity of its territory and defend its national interests. As the world’s fastest supersonic cruise missiles, the Brahmos Missiles will provide deterrence against any attempt to undermine our sovereignty and sovereign rights, especially in the West Philippines Sea”6.

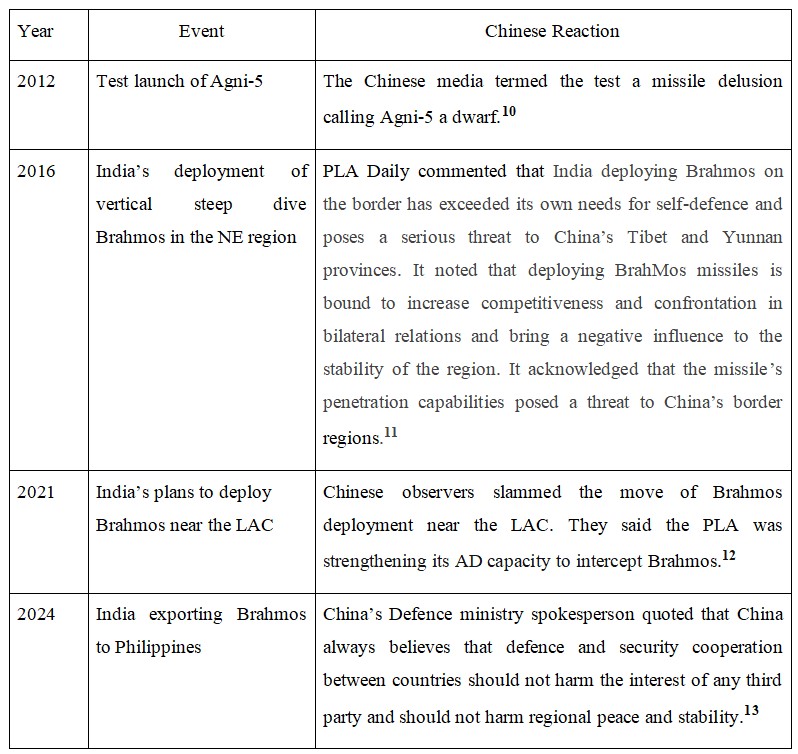

Previous Chinese reactions towards Brahmos:

Looking at the above Chinese reactions, China has clearly shown a concern towards Brahmos deployment. Even though they mocked the Agni-5 test in 2012, even the Chinese experts are now fully aware about the real potential and lethality of the Agni-5. With respect to Brahmos, the Chinese or any other nation is yet to develop a missile defence solution which can counter Brahmos while in manoeuvring or sea-skimming flight. If the Chinese had ever developed a counter AD system to Brahmos, they would have displayed that with some technical or visual data which is unavailable. Recalling our earlier learnings, any indication of fear is enough to generate deterrence. So clearly Brahmos is a threat for the Chinese.

Balance of power dynamics:

Since Philippines and China don’t share any direct land border, the missile capacities of both these nations needs to be analysed in the naval domain only. The Philippines has traditionally lacked the necessary infrastructure and technological base to develop its own missiles. Also, since it had signed the Mutual Defence Treaty with the US in 1951, the US was the primary defence partner of the Philippines and used to supply military equipment. The WPS dispute started gaining momentum from the year 2012 and the Philippines felt the need to acquire weapons to deter China. The NSP 2023 also mentions that the Philippines will try to acquire counter strike systems from other nations. In this regard the US has recently sent its Land/Coastal based Mid-Range Capability (MRC) Typhoon missile system in April 2024 at Northern Luzon with a reported range of 1600 kms.14 China has even rebuked the US for this delivery. Apart from this, in 2023, there was news of the Philippines acquiring the US made HIMARS MLRS which has been used in the Russia-Ukraine war.15 The addition of Brahmos truly is in conformity with what is being envisaged in the NSP-2023 to ensure joint deterrence.

As far as China is concerned, in the naval domain, it has the YJ-18 ASM which can be deployed on their surface ships. It has an estimated range of 540 kms and is said to be deployed in the Type-055 destroyer.16 And as usual with every Chinese weapon being reverse engineered from US or Soviet legacy, the YJ-18 is said to be a copy of the Russian Klub variant ASM as per its flight characteristics. However, the manoeuvrability capabilities of the missile are still unknown or absent, which is one of the important characteristics of any ASM like Brahmos which already possess that feature. As per US experts, the Chinese system lacks the sufficient C4ISR sensors capable of detecting and engaging the target details. Hence the YJ-18 could be blind in absence of any credible C4ISR capability and it would be enough to disable the C4ISR nodes to suppress the YJ-18 during a war time scenario.17

The Chinese AD weapon systems C4ISR reaction analysis has also been observed during the accidental Brahmos firing incident towards Pakistan in 2022. As far as the Brahmos capabilities are concerned, it still retains its tag as the ‘World’s best and fastest supersonic cruise missile’ with only known limitation of range capabilities for its export variant. No doubt for the above similar reason, there have been various efforts by both Pakistan and China to steal Brahmos missile secrets by various means which itself cements the fact that Brahmos capabilities is an envy for India’s adversaries, and they don’t have any credible solution for that. Brahmos test performance has been time and again tested in various environments and that performance data has been validated. The only limitation as of now for Brahmos is its range which is capped at 290 kms for export version.

Lessons for Philippines:

After the above analysis, we now see certain lessons for the Philippines which it can adopt to derive maximum potential out of the Brahmos. To begin with, as discussed earlier, deterrence can be made more effective by adding an element of surprise by not revealing the exact location of the Brahmos missile batteries to be deployed so that the adversary can keep guessing from which direction the impact can happen in times of war. For any future intergovernmental purchase of any other variant of Brahmos, the number of batteries or Mobile Autonomous Launchers to be purchased should not be disclosed to the media or any other misc. source apart from remaining confidential to the top government officials only. This again prevents any adversary from guessing the exact firepower of any deal. We already have noticed one such example in the past Indo-French Rafale deal where the exact value of the deal was not disclosed due to security reasons. As deterrence is also the will to use the weapon, therefore the Philippines political leadership should also formulate a clear written doctrine which should define under what circumstance the system can be used. That will make it more credible. As per manpower training is concerned, the Philippines and Indian governments should quickly expedite the training process of the defence personnel who will be handling the systems.

Philippines has also mulled the idea of collective deterrence via their NPS-2023 vision, they can also think of adding additional means of deterring Chinese vessel aggression by purchasing more anti-radiation radars like India’s ‘Rudram’ missiles which has a capacity to destroy any radar which emits radiation and detects threats. Thereby in a war time situation, by first disabling the radar system of PLAN vessels even partially can enable Philippines to weaken their adversary considerably. India has also integrated the Brahmos missile with their Sukhoi-30 MKI fighter jets in order to deter Chinese naval threats. As the Philippines has plans to purchase fighter jets in future, the integration of Brahmos in those jets could increase the lethality. In the future, the Philippines should also plan to acquire extended range (Brahmos-ER) variants which are either developed or under development phase under MTCR regulations. Finally, the Philippines should increase its defence budget and also purchase more anti-ship weapons to be used in a salvo mode, the devastation of which was partially witnessed during the recent Red-sea crisis.

Conclusion:

The Brahmos missile export to Philippines signifies the arrival of a new strategy in the ASEAN region where Philippines for a long time has tried to have stable and peaceful bilateral relations with China. The previous Philippines President believed in appeasement policy towards China, but the current President’s views are different. In the future, militaries having disputes with China should not look to compete in terms of the sheer number of platforms, rather they should look to increase their payloads, payload quality and effectiveness of their sensor systems. In any war time scenario, it's not the number of platforms(vessels) which matter, but the quality and the number of payloads and counter payloads which will matter. As for India, this export is a welcome signal which will enhance the confidence of other potential nations or buyers who are interested in acquiring the Brahmos system from India. In short, this Brahmos deal is a win-win situation for both India and Philippines.

Endnotes:

1. “BrahMos Signs Contract with Philippines for Export of Shore Based Anti-Ship Missile System.” PIB Delhi, January 28, 2022. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1793209.

2. Rühle, Michael. “Deterrence: What It Can (and Cannot) Do.” NATO Review, April 20, 2015. https://www.nato.int/docu/review/articles/2015/04/20/deterrence-what-it-can-and-cannot-do/index.html.

3. Col, Sr, and Xu Weidi. “Embracing the Moon in the Sky or Fishing the Moon in the Water? Some Thoughts on Military Deterrence: Its Effectiveness and Limitations.” Air & Space Power Journal | 4 International Feature, 2012. https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/Portals/10/ASPJ/journals/ Volume-26_Issue-4/IF-Weidi.pdf.

4. “Deterrence Operations Joint Operating Concept.” US Department of Defense, December 2006. https://www.jcs.mil/Portals/36/Documents/Doctrine/concepts/joc_deterrence.pdf.

5. Marcos, Ferdinand R. “National Security Policy 2023-2028.” National Security Council, Republic of Philippines, August 2023. https://nsc.gov.ph/images/NSS_NSP/National_Security_Policy_2023_2 028.pdf.

6. Department of National Defence, Republic of Philippines. “Shore-Based Anti-Ship Missile System Contract Signed,” January 28, 2022. https://www.dnd.gov.ph/Postings/Post/Shore-based%20anti-ship%20missile%20system%20con tract%20signed.

7. Nicholson, Brendan. “A Little Bit of Fear Is a Strong Deterrent.” The Strategist, May 8, 2018. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/a-little-bit-of-fear-is-a-strong-deterrent/.

8. “Japan’s Passage of Defense Documents Brings Country Away from Track of Post-War Peaceful Development: Chinese Embassy - Global Times.” Global Times, December 16, 2022. https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202212/1282035.shtml.

9. Siow, Maria. “‘Clearly a Concern’: Japan’s Hardening China Stance Sparks Regional Unease.” South China Morning Post, August 7, 2023. https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/politics/article/ 3230075/japans-hardening-china-stance-clearly-concern-behind-closed-doors-does-asean-accept-it.

10. BBC News. “Chinese Media Mock India’s ‘Dwarf’ Missile.” April 20, 2012, sec. Asia-Pacific. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-pacific-17784779.

11. Laskar, Reazul H. “China Warns India against Deploying BrahMos Missile in Arunachal Pradesh.” Hindustan Times, August 22, 2016. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/china-warns-india-against-deploying-brahmos-missile-in-arunachal-pradesh/story-ui0psBJZ3WOvn3aJzLCqiJ.html.

12. Changyue, Zhang. “India’s Plan to Deploy BrahMos Missile Escalates Border Tension, but of No Actual Threat: Observers.” Global Times, November 14, 2021. https://www.globaltimes.cn/p age/202111/1238935.shtml.

13. PTI. “India-Philippines Defence Cooperation Should Not Harm Any Third Party: Chinese Military on BrahMos Missiles Delivery.” The Economic Times, April 26, 2024. https://economictimes.indiatim es.com/news/defence/india-philippines-defence-cooperation-should-not-harm-any-third-party-chinese-military-on-brahmos-missiles-delivery/articleshow/109600035.cms?from=mdr.

14. Lendon, Brad. “US Sends Land-Attack Missile System to Philippines for Exercises in Apparent Message to China.” CNN, April 22, 2024. https://edition.cnn.com/2024/04/22/asia/us-land-attack-missile-philippines-china-i ntl-hnk-ml/index.html.

15. Lariosa, Aaron-Matthew. “Philippines to Acquire HIMARS, More BrahMos Missiles in Coming Years.” Naval News, July 1, 2023. https://www.navalnews.com/naval-news/2023/ 07/philippines-to-acquire-himars-more-b rahmos-missiles/.

16. Missile Defense Project, "YJ-18," Missile Threat, Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 25, 2020, last modified April 23, 2024, https://missilethreat.csis.org/missile/yj-18/.

17. Subramanian P, Arjun. “YJ-18 ASCM Another Leaf from Russian Technology: Reverse Engineered and Improved.” CAPS India, December 31, 2015. https://capsindia.org/wp-content /uploads/2021/10/CAPS_Infocus_AS_20.pdf.