Initiation of Quadrilateral Security (Quad) cooperation

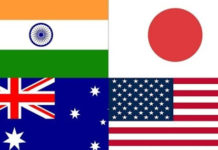

The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue also referred to as Quad, is a strategic consultation framework between the US, Australia, Japan and India. The Quad began nearly seventeen years ago with joint response to a tangible and urgent crisis, the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami. For nine days in December 2004 and January 2005, the navies of the United States, Japan, Australia and India provided rapid and effective relief to injured and displaced people all around the Indian Ocean littoral (Grossman, 2005; Envall, 2015).

On the sidelines of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Regional Forum summit held in the Philippines in August 2007, the four nations met to discuss options for further engagement (Thakur, 2018). The idea was resurrected when Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, addressing the Indian Parliament on 22nd August 2007, brought about the coupling of Pacific and Indian Oceans, called for an “arc of freedom and prosperity” and talked about ‘confluence of the two seas. Quad enjoyed a brief revival when the four countries, along with Singapore, held naval exercises in the Bay of Bengal in September 2007, which drew criticisms from China. By 2008, Australia had expressed concerns about Quad and its impact on Sino-Australian relations and had withdrawn from further dialogue (Smith, 2008). Enthusiasm for Quad subsequently dissipated and the idea largely disappeared from national diplomacy (Envall, 2018).

Renewed Interest in Quadrilateral Dialogue

In years since this informal group has become more formalised. It holds meetings, and it has discussed an array of joint initiatives. But Quad has groped for purpose: instead of a quadrilateral that responds jointly to specific functional challenges, the four are today united largely by their shared suspicion of rising of Chinese power. Quad was not dead but merely on hiatus (Envall, 2019). By 2017, renewed interest in dialogue had emerged (Thakur, 2018). The four countries restarted their dialogue, meeting once again in the Philippines, on the sidelines of the East Asia Summit. They promised to pursue “continuing discussions and deepening cooperation based on shared values and principles” (DFAT, 2017). The reason for the resurrection of this ad-hoc grouping in Manila in September 2017 is the changed geopolitics in Indo–Pacific (Wadhwa, 2018). Graham (2018) argues that the future of the new Quad will be shaped primarily by the degree to which there is alignment between four partners’ threat perceptions and national interests. The United States undertook its ‘pivot’ to Asia and the re-election of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe restored Quad’s champion in Japan. Australia’s 2017 foreign policy White Paper emphasised the need for coordinated maritime engagement in the region, and legislation was introduced in December 2017 to curb Chinese influence in domestic politics and education (Sandhu, 2017). The primary reason is China, which has moved aggressively to enter geopolitical and economic space vacated by the United States in Indo–Pacific. China’s position has also shifted considerably as it has pursued island-building in the South China Sea, asserted claims in disputed waters and significantly expanded the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN). The Maritime Silk Road component of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has raised concerns about the intent of this project (Sandhu, 2017). Although all partners of Quad are also cooperating with rising and powerful China, it is using economic inducements and penalties, influencing operations and implying military threats to persuade others to agree to its political and economic agenda. Its infrastructure and trade policies reinforce its desire for political dominance. The assertive policy of China in the South China Sea has resulted in occupation, transformation, militarisation and effective control over a large number of islands in the South China Sea. In the Indian Ocean, China has been aggressively acquiring port assets and potential bases, including in Myanmar, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Maldives, Pakistan, and Djibouti. A ‘Joint Observation Station’ proposed by the Chinese in the Maldives is likely to have military capabilities along with provisions for a submarine base, identical to one in Jiwani, near Gwadar, in Pakistan. The Mukunudhoo Island in the Maldives where China is building observatory is part of the northernmost tip of Maldives, close to northern sea lanes of communication—running between India’s Minicoy Island and northernmost atolls of Maldives—as well as to India’s south and southwest coast. Chinese aggressiveness is driven by the need to acquire resources of oil, minerals and other raw materials around the world. Despite Chinese dominance and use of force vis-a-vis several disputed islands in the South China Sea, its competing claims with Vietnam, Malaysia, Philippines, Brunei and Taiwan on islands and their associated economic zones within the South China Sea will continue and economics and politics will continue to make this area a potential ‘hotspot’ for conflict. Chinese traditional rivalry with Taiwan, tense relationship with Japan and economic rise of Southeast Asia has resulted in the enhancement of strategic significance of this region. A free, open, inclusive, transparent and balanced Indo–Pacific region, where sovereignty and international law are respected and differences are resolved through dialogue, can become a guarantee of enduring security and peace in the region. A revived Quad had its first meeting in the new avatar at the level of middle-level officers in Manila on November 12, 2017, who identified the need to address common challenges of terrorism impacting the region. Quad members were supportive of upholding rules-based order and respect for international law in the Indo–Pacific, ensuring freedom of navigation and overflight, maritime security, peaceful resolution of disputes and increasing connectivity (Wadhwa, 2018). The United States grand strategy still exhibits a strong focus on maintaining its regional hegemony and resisting China’s rise (Nelson, 2017). Japan and India are also seeking to maintain their own regional leadership, check Chinese power (Envall & Hall, 2016). For Australia, as Quad’s lone middle power, building closer relations with great powers of Indo-Pacific has long been viewed as an important national interest (Tow & Envall, 2015; Tow & Envall, 2011). Quad reflects a wider proliferation of strategic partnerships across Asia (Envall & Hall, 2016).

Although some Indo-Pacific commentators have viewed the second Manila meeting as a revival of Quad, it is clear that sustaining the dialogue will be challenging, if some participants have doubts about Quad’s strategic value. The four partners’ common interest in “rules-based” order is clear. In recent years, Japan has been especially active in making this case, such as by promoting Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP11). In 2012, Japan’s Prime Minister Shinzō Abe envisaged a ‘democratic security diamond’ that would help “safeguard maritime commons stretching from the Indian Ocean region to the western Pacific” (Abe, 2012). In 2016, while meeting with India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Abe argued that “free and open Indo-Pacific” was “vital to achieving prosperity in the entire region” (JMFA, 2016).

What divided the four powers in 2007–2008—China’s rise—is now bringing them closer together. When Xi Jinping assumed power in 2012 in China, he began dismantling the “hide your strength, bide your time” strategy, moving instead toward a “community of common destiny” (Tobin, 2019). China’s growing assertiveness has challenged the regional order across a range of issues, including territorial disputes and economic relationships (Economist, 2018). New Quad thus holds out the promise of achieving enmeshment as well as balancing objectives (Envall, 2019).

Former US President Donald Trump seized on this more abstract purpose, viewing Quad as a useful means of countering China’s rise in Asia. Trump’s team made Quad focus on its efforts to foster “free and open Indo-Pacific.” Now Joe Biden administration, which shares its predecessor’s ambivalence toward Beijing, has apparently settled on Quad as a cornerstone of its own regional strategy (Feigenbaum & Schwemlein, 2021).

Quad and ASEAN

A Quad must stick to ASEAN centrality as a pivot on which the Indo–Pacific is viewed and needs to keep ASEAN on its side. India continues to deal with a large and contested land border with China which has now been complicated by the Chinese building China–Pakistan Economic Corridor through a disputed area of Kashmir for an outlet into Gwadar port in Pakistan. China today has an interest in Australian assets and infrastructure. Security concerns about China’s intentions have risen in Japan since a territorial dispute over Senkaku Islands flared up. The U.S. pivot to Asia and its alliance system is under pressure due to Chinese success in dividing ASEAN by political influence and financial doles for weaker and poorer countries, in return for controlling stake in their economies, politics and foreign policies. Despite favourable International Court of Justice ruling in The Hague in its favour on China’s aggressive actions in the South China Sea, China managed to convince President Duterte of the Philippines to pursue bilateral negotiations to settle outstanding issues. Physical proximity in Asia and its geographical location has been used by China to convince ASEAN countries that it is the force to deal with in this part of the world. Many countries in ASEAN are increasingly coming under influence of China due to economic dependence and countries like Laos and Thailand are building high-speed railways from Kunming in China to Malaysia and Singapore. China is offering alternatives over the U.S. for military hardware and joint training exercises. Mutually beneficial ties between Quad and ASEAN would benefit Indo–Pacific and provide benefits to each nation (Wadhwa, 2018).

Quad to build confidence and cooperation between partners

Wadhwa (2018) suggests that Quad needs to build confidence and cooperation within partners, through:

• Maritime security and collaboration, addressing issues related to maritime challenges in the Indo–Pacific region, anti-piracy operations, joint escorts of international shipping, countering emerging maritime threats, maritime domain awareness, intelligence sharing.

• Improving infrastructure and connectivity in wider Indo–Pacific region. China’s Belt and Road Initiative is a means to have greater say in international economic engagements by funding and building global transport and trade links with Asia and Europe.

• Japan has already let it be known that it will promote “Free and Open Indo–Pacific Strategy,” including “high quality infrastructure” with Asian Development Bank (ADB).

• India, under its “Look East Policy,” is funding Trilateral highway connecting its northeast with Thailand via Myanmar by road. India has announced plans to align the project with ASEAN Master Plan on Connectivity and to extend trilateral to Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam later. It is building Kaladan Multi Modal transport system which will link India’s northeast with Myanmar and provide connectivity avenues to Bangladesh.

• At Africa Development Bank meeting in May 2017, strategy called “Asia Africa Growth Corridor,” linking economies, industries and institutions of Africa and Asia was spelt out.

• Japan has emerged as major partner in India’s efforts for development of northeast and connectivity to ASEAN. “Japan India Act East Forum” has been set up, seeking synergies between India’s “Act East Policy” and Japan’s “Partnership for Quality Infrastructure” in ADB.”

• Strengthening cooperation with ASEAN.

• Security cooperation and dialogues, including joint exercises, defense equipment and technology cooperation in areas as surveillance and unmanned system technologies.

• Collaboration in cybersecurity, information and communications technology.

• Coast Guard collaboration and mine-sweeping technologies, anti-piracy operations, joint communications, deep-sea mining and pollution control.

• Developing blue economy, collaborating and working together in maritime security capacity-building for ASEAN and Pacific countries between themselves through groupings like the India Ocean Rim Association, Indian Ocean Naval Symposium, and Western Pacific Naval Symposium to avoid overlaps and duplication of efforts.

• Jointly countering non-traditional threats to security like pandemics, help and rescue at sea, humanitarian and disaster relief.

Amidst deteriorating relationship with China through 2016-17 and persistent calls from the US and Japan to resurrect Quad, India appears to have made a fresh calculation on pluses and minuses of joining the forum. After India gave the green light, senior officials from four countries met on the margins of the November 2017 East Asia Summit in the Philippines. India’s readiness to explore prospects for the Quad mark an important moment in India’s great power relations and the Indo-Pacific construct has now become part of India’s strategic discourse.

Under Prime Minister Narendra Modi, India has also endorsed the conception of ‘free and open Indo-Pacific’ articulated by Abe. By end of 2017, the US too was adopting the theme of free and open Indo-Pacific. In his speech during October 2017 the US Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson called for a hundred-year partnership in Indo-Pacific between the United States and India that was ‘rising responsibly. ‘The world’s centre of gravity is shifting to the heart of Indo-Pacific. The US and India – with our shared goals of peace, security, freedom of navigation, and a free and open architecture – must serve as the eastern and western beacons of the Indo-Pacific. As the port and starboard lights between which the region can reach its greatest and best potential’ (Tillerson, 2017). With the US, military cooperation has gone furthest: India signed the LEMOA agreement which allows both countries to access each other’s bases for refuelling and replenishment on a case by case request. Defence talks with Japan and Australia have deepened. Japan has become a permanent member of Malabar naval exercises. Australia and India for the first time have a defence agreement (Bajpai, 2018).

India and Quad

More than Japan and Australia, it is India, China’s immediate neighbour, that holds key to Quad’s prospects. During his September 2017 visit to India, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe expressed that “powerful Japan and powerful India can protect each other’s interests.” The US, in its National Security Strategy released in December 2017, vowed that it will support India’s role as a “leading global power” in Indo-Pacific by expanding India-US strategic and defence partnerships. Australia has acknowledged India’s importance in Indo-Pacific strategic calculus. India’s role in Quad is driven by New Delhi’s rising ambitions. The US, Japan and Australia want India to play a central and constructive role in shaping Quad’s role in Indo-Pacific (Panda. 2018). The dominant view in India cautions Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi on the dangers of being sucked into an alliance with the United States. If America has become more empathetic since then to India’s concerns on terrorism, Kashmir and global nuclear order, rising China has turned hostile. Tensions on the disputed Sino-Indian border have become more frequent and intense. Russia, which once helped India balance China, is now in a tight embrace with China (Raja Mohan, 2017). India’s decision to revive the Quadrilateral security dialogue with Japan, the United States and Australia is a decisive step towards the consolidation of strategic partnerships with the United States and its Asian allies and in enhancing India’s bargaining power vis-à-vis China. As he seeks a say in defining the agenda of Quad, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi is heralding India’s self-confident pursuit of enlightened self-interest with all major powers.

As an estimated 90% of India’s trade volumes – including 90% of its oil imports– are carried by sea, it has an interest in ensuring the security and openness of key maritime trade routes in the region (Jain, 2017). These interests are reflected in new policy iterations, such as the 2014 Act East Policy, by which New Delhi planned to deepen its economic and security ties with states in the region. India allocated $1billion to promote connectivity between India and ASEAN states and the Indian Navy has conducted multiple bilateral exercises with member-state navies (Sajjanhar, 2016). India has also bolstered its naval ties with Japan, Australia and the United States, in the Indo-Pacific region over the last decade. Malabar exercises with US Navy have expanded to include Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Forces and India has fostered maritime relations with Royal Australian Navy through bilateral exercises since 2015 (Madan, 2016). Commitment to Quad could help India balance against China’s expanding influence in the Indian Ocean. Beijing’s BRI has led to its acquisition of a site for a military facility in Djibouti, as well as major port deals with Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Pakistan (Singh, 2017). Establishing these strategic installations has given China a strong military and economic presence in the Indian Ocean, threatening India’s influence in its maritime neighbourhood. China Pakistan Economic Corridor, which will connect Xinjiang in China to Gwadar port in Pakistan has alarmed India. India has argued that as the corridor runs through Pakistan-occupied Kashmir, it violates Indian sovereignty and gives legitimacy to Islamabad’s claim over the contested area. China dismissed the 2016 decision by the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) that ruled in favour of the Philippines in a matter of disputed territory in the South China Sea (Sandhu, 2018).

Key concerns that pushed India away from Quad a decade ago have continued to dissuade it from pursuing tighter relationships today. Ramifications of a strained relationship with China remain significant calculation when India engages with other states internationally. India has no desire to be a ‘junior partner’ to America that many in India fear. Prime Minister Modi appears quite confident that he can negotiate terms of engagement on the construction of the Quad. Underlying that proposition are three important factors. The first is the extraordinary self-assurance of Modi, who is ready to explore the limits of India’s bargaining power. Second, Modi is aware that China’s rise and political assertiveness, growing regional concerns about China’s unilateralism and America’s efforts to retain its longstanding primacy have generated a rare moment of strategic opportunity to elevate India’s regional standing. Prime Minister Modi wants to develop Quad slowly and deliberately and retain a big say for India in its agenda, heralding an India that is comfortable with playing hard-ball geopolitics in Indo-Pacific (Raja Mohan, 2017).

China will threaten, raise objections and use leverages at hand to scuttle joint action. A payoff or deference to commercial terms or political diktat must be rebuffed and maritime ties strengthened amongst partners for mutual benefit. The object must remain the creation of multi-polar and increasingly connected Indo–Pacific, with processes to assure mutual security of all stakeholders. This process can be consolidated if Quadrilateral Security Dialogue can be converted into a formal process, with regular meetings to coordinate cooperation in security, economic, and political fields with an agreed road map (Wadhwa, 2018).

India shares a common perspective with other Quad members that Indo-Pacific must encourage a ‘rules-based order’. India’s role in Quad is driven by New Delhi’s rising ambitions. Quad’s ‘open-minded agenda’ is relevant to India’s strategic interests and the strategic compatibility that India enjoys with other members. New Delhi’s approach is more to advance India’s position in Indo-Pacific than simply to counter China. First, India sees the Quad as a way of addressing rising power asymmetry in Asia. India has long sought power equilibrium concerning China. China has surpassed India on many accounts to improve its ‘comprehensive national power’ in Asia and the world at large. Beijing under President Xi Jinping’s leadership is pursuing a ‘new era’ in foreign policy strategy that is much more US-centric. China’s emergence as a “revisionist” power comes as a strategic challenge to India’s interests in Asia. To address this power disequilibrium, India finds strategic consonance with Quad members. Second, China’s unilateralism in its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has constrained India’s choice of interests in Asia and elsewhere. China’s Maritime Silk Route (MSR) poses a challenge to India’s maritime superiority in the region, as it focuses on infrastructure along “alternative” routes in the Indian Ocean. China’s increasing assertiveness in the South China Sea, East China Sea, India-China border disputes and its maritime ambitions in the Indian Ocean have further complicated Asia’s geopolitics. These developments have encouraged India to demand that the status quo in the Indian Ocean be upheld in a ‘free and open maritime environment. Quad countries are seen as strategic partners. India looks upon Japan as a financial partner in bolstering its maritime infrastructure, and the United States as a military partner in the region. Likewise, Australia provides strategic comfort to India’s growing Indo-Pacific ambitions. Third, India’s vision of maritime Indo-Pacific is based on an “inclusive” and “consultative” approach that establishes strategic consonance with other democratic countries such as Australia, Japan, and the US. India’s advocacy of Security and Growth for All in the Region (SAGAR), which calls for inclusivity and universalism is proof of this. SAGAR invites all countries to promote transparency and transnationalism in maritime governance (Panda, 2018). India does not want Quad to only focus on military cooperation, but also on economic and financial ones. India wants Western countries to provide it with funding and technology to help build value and industry chains that can replace China. After the COVID-19 outbreak, India has been actively negotiating this with the other three Quad members. One focus of the Quad summit was to announce financing to boost India’s vaccine output. India has been very proactive both bilaterally and multilaterally to promote the development of Quad. In 2019, India upgraded its engagement with Quad to ministerial level. In 2020, India signed Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement for geo-spatial cooperation with the US, included Australia in Malabar military exercise and signed mutual logistics support arrangement with Japan.

India-China Strategic Issues Are Not Going to Go Away

As emerging economies, India and China relate to each other in a range of regional and global fora which include IMF, WTO, World Bank, Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, BRICS, AIIB, BASIC climate group and trilateral Russia-India-China (RIC) group. This makes a Quad comparatively feeble proposition. But India-China border disputes and countries’ growing discord in areas such as water, maritime security and regional politics often make them appear as Asian rivals. India’s strategic consonance with other Quad countries does not guarantee its security and safeguarding of its territorial interests in event of the India-China conflict. Other Quad members broadly support BRI and consensus has not emerged among them to challenge either MSR or BRI. All other members have offered tactical support for the continents-spanning project. India’s participation in the Quad is not an explicit move against China. It is a calculated measure to protect its interests in the rapidly changing Indo-Pacific. Strategic contradictions among Quad countries discourage India from forming a formal alliance against its immediate and largest neighbour (Panda, 2018).

Perspectives and Prospects of Quad

Quad believers tend to see Indo-Pacific Quad as a coherent strategic construct while Quad sceptics dispute this. Quad believers contend that Quad offers a way to manage uncertainties of regional rivalries by embedding them in the Indo-Pacific region, while Quad sceptics view Quad as an ‘empty gesture masquerading as policy’ (Envall, 2019). Quad is not an alternative to China’s BRI, though the four democracies are strengthening collaboration on regional connectivity initiatives that promote good governance, transparency, accountability and sustainable debt financing. Nor does Quad represent a containment strategy targeted at China, a futile proposition so long as China remains the top trading partner for each member of Quad. Quad is a symbolically and substantively important addition to the existing network of strategic and defence cooperation among the four capable democracies of the Indo-Pacific. What makes Quad unique is that its members are powerful enough militarily and economically to resist various forms of Chinese coercion while offering ‘muscle’ necessary to defend the foundations of Free and Open Indo-Pacific from potential challengers (Smith, 2018). Quad needs to be better at developing a more focused agenda (Hall, 2017). Criticism of Quad is that it lacks a common purpose or substantive agenda (O’Neil & West, 2019). Quad partners need to better articulate their own unique rationale for cooperation (Zala, 2018).The idea of cooperation in Indo–Pacific cannot just be centred on China. Quad should have practical agenda of cooperation (Envall, 2019). If the Indo-Pacific concept has any strategic value, it is found in the idea that an integrated maritime geopolitical complex is emerging that links the United States, China and India across Indian and Pacific Oceans (Graham, 2018). Quad is moving to cooperate on supporting regional infrastructure projects (Straits Times, 2017).

A call among Quad countries’ foreign ministers in March 2021 highlighted the need for joint responses to coronavirus pandemic, climate change and other challenges, such as countering disinformation, advancing counterterrorism, assuring maritime security. These four countries cannot solve these issues acting alone and need other partners. The Quad’s future would be best reconceptualised as the core of a set of ad-hoc coalitions that bring in changing cast of partners, where needed, based on capacity and will. Quad is hampered by its nearly exclusive focus on security issues. Its main success to date has been in the increasing tempo of joint military exercises in the region, including through India-led Malabar and U.S.-led Sea Dragon exercises. These military exercises have been useful: they involve planning and conducting drills against specific hypothetical scenarios. But disproportionate focus on security issues has also limited Quad’s growth potential. Expanding maritime surveillance efforts could be one area of continued action. Non-security issues offer the greatest potential for problem-solving and successful action (Feigenbaum & Schwemlein, 2021),

Feigenbaum and Schwemlein (2021) suggest Quad leading ad-hoc regional coalitions in four areas: coordinating best practices for COVID-19 vaccines, addressing climate change, promoting transparent infrastructure financing and bolstering supply chains:

1. Coordinate vaccine best practices: First, Quad should seek to become core of regional coalition that aims to coordinate and share data among various national regulatory bodies for pharmaceuticals and biotechnology across the Indo-Pacific as these bodies review various COVID-19 vaccine candidates.Many countries do not have rapid approval procedures for new medicines and therapies. Quad could coordinate to advance joint recommendations for regulatory best practices and then could seek partners among other countries’ regulatory bodies that would agree to adopt these practices as their baseline national standards. Quad could seek partners to help expand and accelerate vaccine production by broadening pool of licensed private producers. India has special role to play here because it has indigenous vaccine, Covaxin and substantial domestic manufacturing capacity through Bharat Biotech and Serum Institute.

2. Lead on green technology and finance solutions: Second, Quad could lead regional coalitions on green energy innovation and finance. Biden has identified addressing the climate crisis as his administration’s top priority, as have Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Japanese Prime Minister SugaYoshihide. Biden and Suga for their part have committed their countries to achieving net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, while India has made remarkable progress in rolling out new renewable power projects. Coordination among Quad countries could improve cohesion and offer example for others in Asia, by committing to jointly announce new commitments ahead of November 2021 Glasgow UN Climate Change Conference of Parties.

3. Export high standards for infrastructure financing: Third, Quad could jointly drive functional progress on accelerating efforts to raise infrastructure development and finance standards. Under Japan’s leadership, G20 nations convening in Osaka endorsed a set of ‘Principles for Quality Infrastructure Investment’, which were intended to serve as common standards for financing and executing competitive, transparent, and sustainable infrastructure projects. The U.S. International Development Finance Corporation and its Australian and Japanese peers joined the Blue Dot Network, which was announced as a means of certifying compliance with the aforementioned principles. Quad countries should work together to bring others on board—perhaps around the upcoming G7 summit, to which Australia, India, and South Korea have been invited. The goal would be to encourage partners to enact quality infrastructure investment standards their respective development finance institutions.

4. Make supply chains more resilient: Fourth area for joint Quad leadership of ad-hoc coalitions would be improving supply chain resilience. Pandemic-related disruptions have underscored need to protect supply chains. Australia, India and Japan have announced plans to work together to create Supply Chain Resilience Initiative aimed at reviewing current systems for vulnerabilities to potential disruption and exploring potential for shifting production to improve predictability in future (Feigenbaum & Schwemlein, 2021).

Aspirations of Quad

Quad countries strive for a region that is free, open, inclusive, healthy, anchored by democratic values and unconstrained by coercion. Today’s global devastation wrought by COVID-19, the threat of climate change and security challenges facing the region summon Quad countries with renewed purpose. Quad countries commit to promoting a free, open rules-based order, rooted in international law to advance security and prosperity and counter threats to both Indo-Pacific and beyond. They support the rule of law, freedom of navigation and overflight, peaceful resolution of disputes, democratic values and territorial integrity. Quad countries have committed to work together and with a range of partners and reaffirmed their strong support for ASEAN’s unity and centrality. Quad seeks to uphold peace, prosperity and strengthen democratic resilience, based on universal values. Quad countries have pledged to respond to economic and health impacts of COVID-19, combat climate change and address shared challenges including in cyberspace, critical technologies, counterterrorism, quality infrastructure investment and humanitarian assistance and disaster relief as well as maritime domains. Quad will collaborate to strengthen equitable vaccine access for Indo-Pacific, with close coordination with multilateral organisations including World Health Organisation. Quad is united in recognising that climate change is a global priority and will work to strengthen climate actions of all nations, including to keep a Paris-aligned temperature limit within reach. Quad will begin cooperation on critical technologies of the future to ensure that innovation is consistent with free, open, inclusive and resilient Indo-Pacific. Quad will continue to prioritise the role of international law in the maritime domain, particularly as reflected in the United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea, and facilitate collaboration, including in maritime security, to meet challenges to rules-based maritime order in the East and South China Seas.

Epilogue

From a realist perspective, geopolitics is much about establishing spheres of influence; therefore, Indo-Pacific as a geopolitical construct will necessarily involve such competition. While the U.S. seeks to maintain its influence in the region in face of Chinese challenges, it also seeks to boost India‘s influence eastwards of Malacca Straits, and Japan‘s influence in the Indian Ocean. The underlying motivations, levels of engagement and views of Quad as a possible instrument to balance against strengthening Chinese role in the Indo-Pacific region vary for each of the grouping’s members. Despite converging interests among Quad’s members, unsteady normative foundations of the grouping are factors preventing the serious revival of Quad. China’s strategic initiatives in the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean make it imperative to include more countries like Indonesia and the Philippines into security architecture for the region. Quad needs to shift its focus from its novel form of dialogue toward joint functional action by the group on the most pressing priorities that others in the region now face. If other countries in Asia view Quad as little more than a talk shop to discuss looming risks posed by China’s rise while occasionally holding joint military exercises, it is unlikely that other countries will see its utility or view it as a model for their own choices and conduct. Quad countries must demonstrate in action that they are making major contributions to solving larger economic, transnational and environmental challenges that affect others in Indo-Pacific. If it does so successfully, Quad can comprise the firm core of an elastic regional architecture. Priority should not be on countering China for its own sake but on increasing areas of alignment and cohesion with a larger community of potential problem-solving partners. That is the best path for advancing the interests of Quad countries, preserving security and promoting development in the Indo-Pacific.

References

1. Abe, S. (2007). Confluence of two seas. Address to the Indian Parliament, 22 January 2007, http://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/pmv0708/speech-2.html

2. Abe, S. (2012). Asia’s Democratic Security Diamond.Project Syndicate, December 27, 2012, http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/a-strategic-alliance-for-japan-and-india-by-shinzo-abe#5R2zcYPpL6wLTzTF.99.

3. Aso, T. (2006). Arc of Freedom and Prosperity: Japan’s Expanding Diplomatic Horizons.Speech on the Occasion of the Japan Institute of International Affairs Seminar, November 30, 2006, https:// www.mofa.go.jp/announce/fm/aso/speech0611.html.

4. Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) (2017). Australia-India-Japan-United States Consultations on the Indo-Pacific. media release, November 12, 2017,

5. Bajpai, K. (2018). Modi’s Foreign Policy No Better and No Worse than Predecessors. India Seminar 2018,http://www.india-seminar.com/2018/701/701_kanti_bajpai.htm

6. Bhatia, R. K., and Sakhuja, V. (2014). Indo PacificRegion: Political and Strategic Prospects. Vij BooksIndia Pvt. Ltd.

7. Dhar, B. (2018). India’s Free Trade Woes. East Asia Forum, 9thOctober, 2018, http://www.eastasiaforum.org/2018/10/09/indias-free-trade-woes/

8. Envall, H. D. P. (2015). Community Building in Asia? Trilateral Cooperation in Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief.In Yuki Tatsumi (ed.), US-Japan-Australia Security Cooperation: Prospects and Challenges (Washington, DC: Stimson Center), pp. 51–59.

9. Envall, H. D. P. (2018). The ‘Abe Doctrine’: Japan’s New Regional Realism.International Relations of the Asia-Pacific, pp. 1–29, doi:10.1093/irap/lcy014

10. Envall, H. D. P. (2019). The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue: Towards an Indo – Pacific Order? Policy Report. S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

11. Envall, H.D.P. and Ian Hall (2016). Are India and Japan Potential Members of the Great Power Club? In Joanne Wallis and Andrew Carr (eds.), Asia-Pacific Security: An Introduction Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 63–81.

12. Feigenbaum, E.A. & Schwemlein, J. (2021). How Biden Can Make the Quad Endure. 11th March 2021, Carnegie Endowment.https://carnegieendowment.org/2021/03/11/how-biden-can-make-quad-endure-pub-84046

13. Graham, E. (2018). The Quad Deserves its Second Chance.In Andrew Carr (ed.), Debating the Quad, Centre of Gravity series paper 39 (Canberra: Strategic and Defence Studies Centre, ANU, pp. 4–7.

14. Grossman, M. (2005). The Tsunami Core Group: A Step toward a Transformed Diplomacy in Asia and Beyond, Security Challenges,Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 11–14.

15. Hall, I. (2017). Advancing the Quad through Diversification.Lowy Interpreter, 30thNovember, 2017, https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/advancing-quad-through-diversification

16. Jain, B.M. (2017). India’s Security Concerns in the Indian Ocean Region: A Critical Analysis.Future Directions, 4th April 2017.

17. Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2016). Japan-India Joint Statement. 11thNovember, 2016. https://www.mofa.go.jp/files/000202950.pdf.

18. Madan, T. (2017). The Rise, Fall, and Rebirth of the ‘Quad.War On the Rocks, 16th November 2017, available at https://warontherocks.com/2017/11/rise-fall-rebirth-quad/

19. Medcalf, R. (2017). An Indo-Pacific Quad is the Right Response to Beijing.Australian Financial Review, 8thNovember, 2017, https://www.afr.com/news/economy/an-indopacific-quad-is-the-right-response-to-beijing-20171108-gzh3c7

20. Nelson, L. (2017). In Asia, Trump Keeps Talking about Indo-Pacific. Politico, 7thNovember 2017, https://www.politico.com/story/2017/11/07/trump-asia-indo-pacific-244657

21. Nicholson, B. (2007). China Warns Canberra on Security Pact. Age, June 15, 2007, https://www.theage.com.au/national/china-warns-canberra-on-security-pact-20070615-ge54v5.html?page=fullpage#contentSwap1

22. Panda, A. (2018). India, the Quad, and the China Question.Asia Global Online, 12th April 2018.https://www.asiaglobalonline.hku.hk/india-china-quad/

23. Raja Mohan C. (2017). India and the Resurrection of the Quad. ISAS Brief No. 525, 17th November 2017. Institute of South Asian Studies, Singapore.

24. Sajjanhar, A. (2016). 2 Years On, Has Modi’s ‘Act East’ Policy Made a Differencefor India? The Diplomat, 3rdJune 2016.

25. Sandhu, J. (2018). India and the Quad: BalancingNational Interests and Regional RealitiesCanadian Naval Review Vol. 13, No. 4.

26. Smith, J. (2018). The Return of Indo-Pacific Quad. The National Interest, 26th July 2018. https://nationalinterest.org/feature/return-indo-pacific-quad-26891

27. Smith, S. (2008). Joint Press Conference with Chinese Foreign Minister. February 5, 2008,https://foreignminister.gov.au/transcripts/2008/080205_jpc.html.

28. StraitsTimes(2018). US-backed ‘Quad’ Quietly Gains Steam as Way to Balance China. November15, 2018, https://www.straitstimes.com/asia/east-asia/us-backed-quad-quietly-gains-steam-as-way-to-balance-china.

29. Tillerson, R. (2017). Defining our relationship with India for the next century. Washington DC, 18 October 2017; https://www.state.gov/secretary/remarks/2017/10/274913.htm

30. Wadhwa, A. (2018). The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue: An Alignment of Policies for Common Benefit, Vivekananda International Foundation, Quad-Plus Dialogue Tokyo, Japan March 4-6, 2018.

31. http://thf_media.s3.amazonaws.com/Quad%20Plus/2018%20Conference%20Papers/Wadhwa,%20Anil%20-%20The%20Quadrilateral%20Security%20Dialogue%20an%20Alignment%20of%20Policies%20for%20Common%20Benefit_JLedit.pdf

32. White, H. (2016). The Indo-Pacific: Talking About It Doesn’t Make It Real.Strategist, 22ndNovember, 2016, https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/indo-pacific-talking-doesnt-make-real/

33. White, H. (2017). Why the US is No Match for China in Asia, and Trump Should Have Stayed at Home and Played Golf. South China Morning Post, 15th November, 2017, https://www.scmp.com/comment/insight-opinion/article/2120010/why-us-no-match-china-asia-and-trump-should-have-stayed-home;