Abstract

Stampede refers to sudden rush of crowd of people, usually resulting in many injuries and death from suffocation and trampling. In stampede, term crowd refers to congregated, active, polarized aggregate of people, which is basically heterogeneous and complex. Incidents of stampedes can occur in numerous socio-cultural situations. Most crowd disasters are man-made, which can be completely prevented with proactive and holistic planning and flawless execution. Majority of crowd disasters in India and developing countries have occurred at religious places while stadia, venues of music concerts, night clubs and shopping malls have been typical places of disasters in developed countries. This paper discusses crowding, stampedes, crowd management techniques to prevent stampedes

Key Words: Crowding, Stampedes, Crowd Management, Mass Gathering

What are Mass Gatherings?

Mass gatherings of persons have been defined by World Health Organization (2008) as ‘more than a specified number of persons at a specific location for a specific purpose for a defined period of time’. Mass gathering is explained as an organised event in defined temporary facilities or open space involving gathering of participants and spectators during which an emergency response may be delayed by virtue of limited access or other challenges (Arbon, Bridgewater and Smith 2001; Milsten, Maguire, Bissel and Seaman, 2002; Arbon, 2007; Lund, Gutman and Turris, 2011).

What is Stampede?

Stampede refers to sudden rush of crowd of people, resulting in many injuries and death from suffocation and trampling. The term crowd here refers to congregated, active, polarized aggregate of people, which is heterogeneous and complex. Stampedes are characterised by surge of individuals in a crowd, in response to perceived danger or loss of physical space.

Causes of Stampedes in Mass Gatherings

Rush and surge of people:People try to enter into special place for better view / participation in functions which results in jostling, suffocation, failure of walls and gates.

Accidents: Collapse of structures, accidents on bridges, vehicle accidents

Natural or human induced hazards:Heavy rain and slippery surfaces, fire, intentional acts.

Rumours:: Spread of rumour about accident, terror attack, stampede or calamity.

Competition for procurement:People rush to obtain a valued material, seat, free gifts.

Sudden notice:Sudden change in venue, platforms, counter.

End-of-event exit surge:Sudden propensity of crowds to exit as fast as possible.

Human stampedes are influenced by number of factors related to biomedical, environmental and

psychological domains (Arbon, 2007).

These stampede incidents provide idea about where stampedes

can occur.

• Entertainment events

• Food distribution

• Processions

• Natural disasters

• Power failure

• Religious events

• Riots

• Sports events

• Weather related

These have been categorised into six categories, namely Structural, Fire / Electricity, Crowd Control, Crowd Behaviour, Security, and Lack of coordination between various stakeholders.

Structural

• Structure collapses / temporary structural collapses

• Barricades / bamboo railings / wire fence / Metal barrier collapse

• Makeshift bridge collapses / collapse of railings of bridge

• Poor guard railings / poorly lit stairwells / narrow stairs

• Narrow and very few entry / exits / absences of emergency exits

• Difficult terrain / sloped gradient / Narrow streets / slippery roads

Fire/Electricity

• Fire in makeshift facility or shop

• Cooking in makeshift facility

• Wooden structure/ quick burning acrylic catching fire / tent catching fire

• Non-availability of fire extinguisher/fire extinguishers not in working condition

• Unauthorised fireworks in enclosed places

• Elevators catching fire, people on higher floors panic, steep stair designs

• Electricity supply failure creating panic and triggering a sudden exodus

• Inappropriate fittings such as Aluminium wires instead of copper wires

• Short circuit from electrical generator

Crowd Control

• Sudden opening of entry door

• No access control

• Closed / locked exit

• Reliance on one major exit route

• Limited holding area before the entrance

• People allowed in excess of holding capacity due to overselling of tickets for an event

• More than anticipated crowd at store / mall / political rallies / examinations / religious gatherings / public celebrations

• Uncontrolled parking and movement of vehicles

Crowd Behaviour

• Mad rush to exit

• Sudden flow of people in reverse direction

• A wild rush to force way towards entrance / exits

• Crowds attempting to enter venue after start / closing time

• A collision between large inward flows and outward flows

• Free distribution of gifts/ food/ alms/ blankets/ cash/ clothes triggering surge and crush

• Rush during distribution of disaster relief supplies

• Sudden mass evacuation because of natural disaster

• Large number of pilgrims trying to board ferry for sacred island site

• Mad rush to leave a school

• Tussle to catching glimpse / autograph of celebrity

• Tussle to touch feet of celebrity / religious leader

• Rumours of landslide caused by rains leading to rush down a narrow stairway

• Angry crowd due to delay in start of event / late trains

• Last minute change in platform for train arrival / departure resulting in lots of movements within short time window

• More than expected crowd gathering / More than capacity gathering

• Rush to get covered / free / unnumbered seats at venue

• Scramble to get event tickets

• Crowds trying to re-enter venue (flows inward / outward flows mixed)

• Unruly and irresponsible crowd behaviour

Security

• Security agency using force leading to panic and stampede

• Ineptitude of police in effectively managing crowd / Crowd forced against sharp metal fencing

• Absence of walkie-talkies for police on duty / Absence of public announcement systems or effective wireless system with police

Lack of Coordination between Stakeholders

• Communication delays

• Coordination gap between agencies

• Inadequate medical assistance, public transport, parking facilities / Poor infrastructure

Multiple deaths and injuries at mass gatherings have occurred consistently, over wide spectrum of events and countries (Hanna, 1994). People die in stampedes mostly due to suffocation under high pressure on their chests generated by push of crowd (Fruin, 1993).

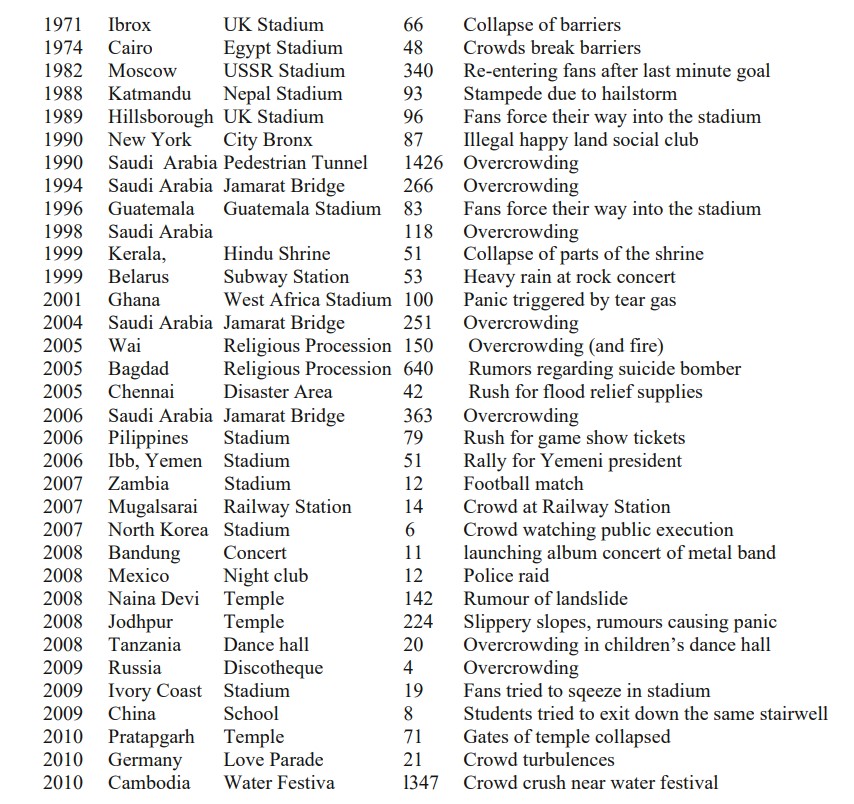

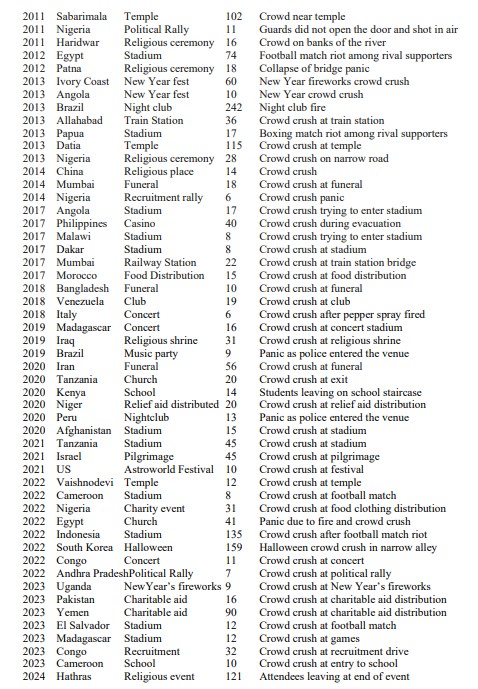

List of some crowd disasters since 1970 to 2024

Air Raid Shelter

In 1943 during World War II, 173 persons died of compressive asphyxia and 92 injured in London Underground air raid shelter after someone fell on lower-level entry stair. Excited by sounds of bombing, people at surface continued to press forward. This resulted in tangled mass of humanity on the stair that took rescuers three hours to unravel (Dunne, 1943).

Funeral Procession

Untold hundreds were killed in Moscow, Russia during massive procession of 3 million people viewing the body of Joseph Stalin after his death in 1953. Army tanks and trucks to control movement of crowd blocked side streets along the route to Stalin's bier. Police and military beat people with clubs to further control crowd, even as people were fatally crushed against building walls, parked tanks and trucks (Pozner, 1990).

Sporting Event Egress

Major crowd incidents in soccer stadia occur with deadly regularity. In 1971, 66 people were killed and many injured at Ibrox Park Stadium in Glasgow, Scotland. Fans began to leave the stadium in last moments of a scoreless match. As game ended, goal was scored. The roar of the crowd caused some to attempt reentry, while mass exited. The resulting conflict caused pile of bodies "about 10 feet high" (Canter et al., 1989). In 1981, 24 Greek soccer fans were killed in Athens stadium as capacity crowd of 45,000 attempted to leave shortly before end of the match. The fans in front ranks found exit gates were locked, but those in rear continued to press forward. In 1982, 340 people were reported killed at match in Moscow's Lenin Stadium.

In 1989, 94 persons were asphyxiated and 174 injured at Hillsborough Stadium in Sheffield, England. A larger than expected group of fans striving to enter the Stadium caused police to open gates to relieve crowd pressures. Instead of relieving pressures, resulting surge of fans into enclosed terraces created critical overcrowding (Hillsborough Stadium Disaster Interim Report, 1989). In 1985, 10 were killed and 30 injured in Mexico City where locked gate blocked hundreds of fans attempting to force their way into the stadium through two tunnels. In 1991, nine persons were asphyxiated in pileup at bottom landing of gymnasium stair at City University of New York. A celebrity basketball game was scheduled in gymnasium and excess of people arrived for the well promoted event. Doors at lower landing entry to gymnasium opened only outward, in compliance with fire codes. People precariously queued on the stair were driven into restricted landing and closed doors by crowd pressures from above (Mollen, 1992).

Riot

In 1985 riot by English and Italian fans in stands at European Cup final at Heysel Stadium in Brussels, precipitated flight of spectators that resulted in 38 deaths by asphyxia and 437 injured.

Weather

In 1988 more than 100 persons died and 700 others were injured at Nepal's National Stadium in Katmandu. A sudden violent hailstorm caused 30,000 spectators to flee open grandstand but found exit gates were locked.

Religious Events

In 1990, 1426 people were killed in crowd crush during annual pilgrimage of 2 million at Mecca, Saudi Arabia. The crush occurred in 500 m long tunnel joining Mecca and Tent City of Mina.

In 1986, 46 pilgrims died in Hardwar, India on crowded bridge across Ganges River where as many as 4 million Hindus gather to bathe in Ganges at Khumb Mela festival.

During 1980 world tour of the Pope, 13 people were killed in two African cities in crowd rushes.

Power Failure

In 1981 45 persons died 27 of them children, in Qutab Minar tower, New Delhi. A blackout, combined with what some witnesses said were cries that tower was falling, triggered sudden exodus of 300 to 400 people.

Food Distribution

In Bangkok, Thailand 19 persons died as crowd of 3,000 assembled to obtain packages of free food. The crowd was attempting to press through a gate approximately 13 ft. wide into meeting hall where food was being distributed.

Entertainment Events

In 1979, 11 young rock music fans were asphyxiated in crowd crush outside Cincinnati, Ohio Coliseum. After 10,000 persons had entered the venue, 8,000 were still waiting to enter general admission event. A warm-up band started playing and fans outside thought concert had begun. Only two doors were opened for entry (Wertheimer, 1980). In 1991, 3 rock music fans died of compressive asphyxia at festival event in Salt Lake City, Utah. Fans standing in open area in front of concert stage pressed forward, causing some to fall, and others to be forced on top of them.

Escalators and Moving Walkways

Passenger conveyors have characteristic of continuously delivering people without regard to outlet conditions. When restrictions at outlet limit discharge rate, pileup will occur (Fruin, 1998). In 1964 one child was killed and 60 children injured at outlet end of Baltimore Maryland Stadium escalator. The escalator was set up for egress day before with one-person wide gate at top. The escalator was reversed for entry next day, but gate was not removed.

Soomaroo and Murray (2012) compiled incidents of mass gathering disasters for period between 1971 and 2011 through search of peer reviewed publications. Hsieh et al. (2009) reviewed human stampede events from 1980 to 2007 and found that 215 stampedes had been reported worldwide with 7069 deaths and more than 14,000 injuries. Developing countries are more vulnerable to stampedes during mass gathering events, with eight-fold higher fatality rate than in rest of the world (Burkle and Hsu, 2011). The deadliest three human stampedes in world over past century include stampede in Baghdad during religious procession in 2005 (965 fatalities), Mina Valley during annual Hajj in 2006 (380 fatalities) and Phnom Penh black Friday shopping stampede in 2010 at Cambodia with 347 fatalities (Hsu, 2013).

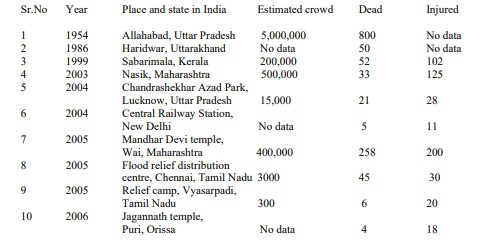

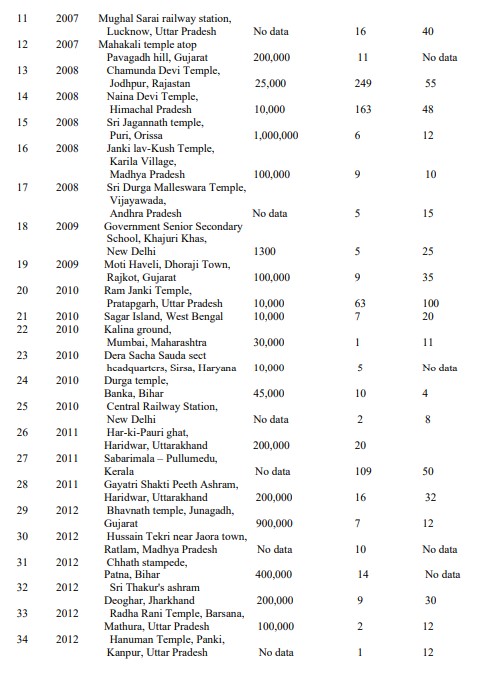

Human stampedes in India

The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), the Information Technology Division of Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India maintains the record of crime and unnatural death in India. NCRB report on ‘Accidental deaths and Suicides in India’ has consolidated the number of stampede deaths since 1996.

List of some crowd disasters since 1970 to 2024

Sample of Recent Crowd Disasters in India (National Disaster Management Authority, 2014)

December 23, 1995: In Dabwali, Haryana, 446 died in fire at school function held in shamiyana (tent)

February 24, 1997: In Baripada, Odisha 206 people died in fire at religious congregation.

June 13, 1997: In Uphaar Cinema, Delhi, 59 people died in trying to come out of smoky cinema hall.

January 15, 1999: 51 Hindus killed and 100 injured in stampede after part of shrine collapsed at hilltop at Pamba, in Kerala where over 1.5 million present for ceremony.

September 28, 2002: In Charbaug Railway Station, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, 19 people died on stairs

January 25, 2005: Hindu pilgrims stampede during Shri Kalubai Yatra Mandhardev temple near Wai, Maharashtra. 265 killed and 100s injured. The stampede was caused by slippery steps leading to the temple.

August 24, 2005: 56 died, hundreds injured in stampede at Vaishnavi Devi temple.

December 2005: Flood relief supplies were handed out to homeless refugees in southern India 42 killed.

August 27, 2003: Nasik, Maharashtra, 29 pilgrims died during Kumbh mela processions

October 3, 2007: Train station in northern India, killing 14.

August 3, 2008: A human stampede at the Hindu temple of Naina Devi occurred on 3 August 2008 in the state of Himachal Pradesh. 162 people died when they were crushed, trampled, or forced over side of ravine by movement of large panicking crowd, after rumours of landslide triggered a stampede.

September 30, 2008: 147 people were killed during the Chamunda Devi stampede at Chamunda Devi temple in Jodhpur, India

March 4, 2010: At least 71 killed and over 200 injured at Ram Janki Temple in Kunda, India

March 4, 2010: Thousands of villagers who came to popular ashram in northern India for free meal on Thursday were caught in stampede, which left more than 60 dead.

January 14, 2011: This took place at Sabarimala in Kerala. It broke out during an annual pilgrimage, killing 106 pilgrims and injuring about 100 more.

November 8, 2011: 20 people died at Har-ki-Pauri at Ganga Ghat in Haridwar, Uttarakhand.

January 14, 2012: At least 10 people, including six women were crushed to death in middle of night when stampede broke out at religious shrine in central India.

February 2012: Human stampede occurred at Bhavnath temple on foothills of Mount Girnar, Gujarat during festive Mahashivrathri day. Approximately 900,000 people gathered on the day for offering prayers. Breakdown of two transport buses on a bridge created crowd disturbances which finally lead to seven deaths with 12 injured.

November 19, 2012: 20 people died as makeshift bridge caved in at Adalat Ghat in Patna.

February 10, 2013: During Hindu festival Kumbh Mela, stampede broke out at train station in Allahabad, Uttar Pradesh, killing 36 people including 26 women and injuring 39.

October 13, 2013: In Ratangarh, Datia, Madhya Pradesh, 121 people died in stampede on a bridge where section of railings broke after more than 150000 people gathered to celebrate Navratri.

October 3. 2014: 30 people died, and 26 others were injured at Gandhi Maidan in Patna

January 14, 2015: A stampede on banks of Godavari River in Rajamundry, Andhra Pradesh, resulted in death of 26 people.

January 1, 2022: Over a dozen died at Mata Vaishno Devi Shrine in Jammu and Kashmir after huge crowd of devotees tried to go into the shrine through its narrow entrance.

July 2, 2024: At least 121 people died in stampede during religious congregation in Hathras district of Uttar Pradesh. Barring seven children and a man, all casualities were women. The victims were part of crowd of thousands that had gathered near Phulrai village in Sikandrarau area for ‘satsang’ by religious preacher Bhole Baba. The stampede took place around 3.30 p.m. when Baba was leaving the venue.

Event Access Points

One key structural element to an event venue is provision of adequate site access, not only for participants but also for emergency medical services.

The Ibrox stadium disaster in 1971 involved fans leaving stadium getting caught up with fans entering stadium at same time, leading to crush and stampede when all fans heard goal being scored (Eliott and Smith, 1993). Further episodes of crowd convergence have occurred at stampede causing death of 1,426 during the Hajj in 1990 where pilgrims spontaneously rushed to leave Mecca via one exit (Ahmed, Arabi and Memish, 2006), and during Love Parade in Germany 2010 where overcrowding led to devastating consequences in tunnel providing only means of entrance and exit to fans of music festival (Garcia, 2011; Ackermann et al., 2012).

To address this, many mass gathering events now have access points solely for entrance or exit at site, promoting unidirectional flow of crowd members and dramatically reducing risk of crowd convergence. Emergency medical services unable to access event sites was found to be major factor in prolonged response time to Ramstein air show disaster, where members of Italian Air Force display team collided and crashed to ground (Martin, 1990). While at traditional festival in Cambodia, no access routes were available for emergency medical services to stampede, severely hindering medical response (Hsu, 2011). It is suggested planning for future events includes provision of easy, unobstructed access for Emergency Medical Service vehicles.

Fire Safety Measures

Fire safety has become increasing part of emergency planning; however, several lessons can still be identified. The stardust fire in Dublin 1981 was thought to have been deliberately started from ignition of newspapers under flammable seats resulting in 48 deaths and 128 injuries (Tribunal of Enquiry Report, 1982). The Bradford City Stadium Disaster is thought to have started by dropped match or cigarette falling through floorboards to rubbish below (Popplewell, 1986). 441 deaths occurred at Indian wedding due to synthetic cloth tent catching fire in large area with no means of emergency exit (Moddie, 2004) and 375 attendees were caught in nightclub fire in Gothenburg, Sweden when venue was only supposed to hold 150 with fire starting in front of emergency exit (Eksborg,1998). Only one of three emergency exits were available during nightclub fire in Volendam, Netherlands (Juffermans and Bierens, 2010).

All fire disasters had similar attributes that emergency planners should consider when planning for mass gathering: Several emergency exits should be made available at any planned event. Emergency exits should be free from obstruction, not blocked and functioning properly, with appropriate signage. Adherence to fire safety protocols is key including prevention of overcrowding of venues. Event employees should be allotted specific duties to be performed in the event of the fire, with regular fire drills held on the premises. Full site fire evacuation plans are essential. These could include signage to evacuation points.

Medical Preparedness

Provision of on-site physician-level medical care at mass gatherings has been shown to significantly reduce number of patients requiring transport to hospital and therefore reducing impact on local ambulance services (Grange, Baumann and Vaezazizi, 2003). The majority of non-disaster injuries and medical complaints at mass gathering can be effectively treated on scene, which reduces number of hospital referrals and patient presentation rates to hospital (Olapade-Olaopa, Along, Amanor-Boadu and Sanusi, 2005).

Following the Hillsborough Stadium disaster 1989, Lord Justice Taylor (1990) made suggestions to improve on-site medical care. On-site medical care has also dramatically improved following several stampedes occurring during annual Islamic pilgrimage of the Hajj (Ahmed, Arabi and Memish, 2006). The most notable event in 2006 resulted in 346 deaths at bottleneck area in Mina Valley. The provision of specially equipped medical care facilities, helipads, electronic surveillance, shading and cooling mists have helped to reduce crowd morbidity and mortality (Ahmed, Arabi and Memish, 2006).

Local hospitals should also be involved with emergency planning in preparation for potential mass gathering disasters. Madzimabuto (2003), in a review of stampede at football match identified following hospital preparedness deficiencies identified as:

a. Emergency department only first aware when injured arrived

b. No major incident plan was prepared

c. A hospital command centre was not set up

d. Staff reinforcements were unable to be contacted

e. Medical teams were not organised to prioritise mass casualty care

f. The media arrived, distracting emergency department personnel

g. Supporting hospitals were not involved in a timely manner

Feliciano, Anderson and Rozucki, (1998) reported that there was extensive pre-Olympics preparation at regional Level 1 trauma centre before Atlanta Games in 1996. In particular pre-hospital training resulted in an excellent hospital-wide response to multi-casualty event following explosion of pipe-bomb in Centennial Park during these 1996 Olympics which resulted in 1 death and 21 injured on scene.

Emergency Response

Many of case reports highlighted poor response time for emergency services but it is unknown if each event reviewed had mass gathering major incident plan available. Poor initial communication with emergency medical services was key finding in not only Ramstein air show disaster (Martin, 1990), but also in stampedes at Miyun Country bridge disaster in China (Zhen, Mao and Yuan, 2008), Akashi firework event in Japan (Takashi et al., 2002) and at religious temple in Uttar Pradesh (Burkle and Hsu, 2010). These highlighted poor triages of casualties. Indeed, in one instance it was triage was initiated approximately 80 minutes after incident occurred (Takashi et al., 2002). One analysis of medical care at mass gatherings by Sanders, Criss and Steck (1986) suggested: Basic first aid within 4 minutes, Advanced Life Support within 8 minutes, Evacuation to medical facility within 30 minutes. Event preplanning using these principles has been described by Ackermann et al. (2011) in relation to 2010 Love Parade in Germany when major medical preparations were put in place. They reported on patient care delivery at this mass gathering, where following a stampede, 21 died and over 510 were injured. Once disaster was called at site, additional emergency healthcare personnel were brought in and extra treatment facilities were created to deal with the situation.

Panic Crowd Dynamics

Most research into panic has been of empirical nature (Elliott and Smith, 1993; Canter, 1990), carried out by social psychologists and others. They are usually distinguished into escape panic (‘stampedes’) and acquisitive panic (‘crazes’) (Miller, 1985). It is often stated that panicking people are obsessed by short-term personal interests uncontrolled by social and cultural constraints (Miller, 1985). This is possibly a result of reduced attention in situations of fear which also causes that options like side exits are mostly ignored (Elliott and Smith, 1993). It is, however, mostly attributed to social contagion (Miller, 1985) This ‘herding behavior’ is in some sense irrational, as it often leads to bad overall results like dangerous overcrowding and slower escape (Elliott and Smith, 1993).

Situations of Panic Crowd Dynamics

Panic stampede is one of most tragic collective behaviors (Miller, 1985) as it often leads to death of people who are either crushed or trampled down by others. While this behavior may be comprehensible in life-threatening situations like fires in crowded buildings (Elliott and Smith, 1993), it is hard to understand in cases of rush for good seats at pop concert (Johnson, 1987). Systematic empirical studies of panic are rare (Miller, 1985) and there is a scarcity of quantitative theories capable of predicting crowd dynamics at extreme densities (Still, 2000). The following features appear to be typical:

1. In situations of escape panic, individuals tend to develop blind actions

2. People try to move considerably faster than normal.

3. Individuals start pushing and interactions among people become physical in nature.

4. Passing of a bottleneck frequently becomes in coordinated.

5. At exits, jams are building up.

6. The physical interactions in jammed crowds can cause dangerous pressures which can bend steel barriers or tear down brick walls.

7. Escape is slowed down by fallen or injured people turning into “obstacles”

8. People tend to show herding behavior.

9. Alternative exits are often overlooked in escape situations

Crowd Disaster Process

When this happens, as explained by Fruin (1993), the FIST circumstances namely crowd Force, Information (false or real) upon which crowd acts, physical Space (seating area, chairs, corridors, ramps, doors, lifts etc.) involved, and Time duration of the incident (rapid ingress/egress) play very important role resulting in either overcrowding (high crowd density: large number of people per unit area) or high desired velocity (accelerated movements). On occasions, this has led to deaths because of crushing, suffocation, and trampling. A mere glance through list of causes of crowd disasters suggests that most of them are manmade, which can be completely prevented with proactive and holistic planning and flawless execution. A thorough assessment of arrangements made at places of mass gathering against above list of potential causes should dramatically reduce chances of a disaster

In last few years, India has witnessed many natural disasters and is at risk to man-made disasters as well. These disasters, natural, man-made or hybrid, typically, result in large number of casualties along with societal agony and huge economic loss. Acknowledging this, India decided (by an act of the parliament: Disaster Management Act, 2005) to move from reactive and response centric disaster management approach to proactive and holistic one.

The Disaster Management Act, 2005 (Chapter 1, Section 2 (e)) defines disaster management as follows:

"Disaster management" means a continuous and integrated process of planning, organizing, coordinating and implementing measures that are necessary or expedient for- prevention of danger or threat of any disaster; mitigation or reduction of risk of any disaster or its severity or consequences; capacity-building; preparedness to deal with any disaster; prompt response to any threatening disaster situation or disaster; assessing the severity or magnitude of effects of any disaster; evacuation, rescue and relief; rehabilitation and reconstruction;

Planning

The important aspects of planning for events/ places of mass gathering include understanding the visitors, various stake holders and their needs; Crowd Management Strategies; Risk Analysis and Preparedness; Information Management and Dissemination; Safety and Security Measures; Facilities and Emergency Planning; and Transportation and Traffic Management.

Know Your Visitors and Stakeholders

The basic element of event / venue planning is to understand visitors. This is largely determined by type of event (religious, youth festival, school / university event, sports event, music concerts, political gathering); season in which it is conducted and type and location of venue (temporary / permanent, open / confined spaces, bus stand, railway station, plain / hilly terrain). Based on this and from prior knowledge and experience, one should attempt to determine type of crowd expected and their estimated numbers. Intelligence has to be gathered about motives of various visitors (social, entertainment, political, religious, economic etc.) and unwanted visitors (theft, disruption, terror etc.). Venue managers must identify various stakeholders and acknowledge their objectives. While planning events, shrine management and security personnel desire high degree of orderliness but local shop owners, priests and their economic interests cannot be ignored. Community stakeholders (NGOs, business associations, schools/colleges, and neighbourhood associations) should be encouraged to take ownership in events.

Crowd Management Strategy and Arrangements

The crowd management strategy and arrangements are required during arrival of crowds, during event and during departure.

The various elements of crowd management strategy are:

a) Capacity Planning

b) Understanding Crowd Behaviour

c) Crowd Control, and

d) Stakeholder approach.

Capacity Planning

In India, religious places have high probability of crowd disasters. Obviously, their locations have also played some role in crowd disasters. A large number of religious sites in India are located atop hills / mountains with difficult terrain and have narrow, winding uphill pathways along steep hillsides where access routes are prone to landslides and other natural dangers. Development of Shrine locality is absolutely necessary in developing infrastructure for Crowd Management, as these places are seeing huge increase in number of visitors

Overall location Development Plan

Staging Points (queue complex): Plan for locations through which each visitor must pass. Each staging point should have sufficient facilities for rest, food, water, hygiene. An effective way of counting / monitoring visitors passing through staging point should be installed to regulate flow.

Multiple routes should be encouraged (normal, express, emergency) with varying route gradient

Understanding Crowd Behaviour

The individuals within a crowd may act differently than if they were on their own. The unlawful actions of few people can result in larger numbers following them. Inappropriate or poorly managed control procedures may precipitate crowd incidents rather than preventing them.

Crowd Control

Crowd Control Staff should be in Uniform and should be in position to communicate with each other and also to the crowd. There should be ample entrances and exits at event and they remain unobstructed.

Managing Demand-Supply Gaps

i) Control crowd inflow ii) Regulate crowd at venue and iii) Control the outflow

Understanding the Demand

Understand historical numbers, crowd arrival patterns, growing popularity, type of visitors. Identify mass arrival time windows creating peaks (season, days of week, time in the day, festivals, holidays etc.). Have knowledge of public transport timetables.

Understanding the Supply

Calculate capacity at venue: seating capacity; worships, offerings or prayers possible per hour etc. Calculate capacity of holding areas/ queue complex. At number of places, demand outstrips supply, leading to overcrowding. Because of this, there is a need for an input control. Restricting number of entries. A mandatory registration process makes this possible. Influencing arrivals. This can be done through: Informing off-peak times. Have priority queues, visitors with advanced/internet booking.

Stakeholder Approach

Organizers / Temple trusts, Law enforcement agencies must rethink crowd control. Community stakeholders (NGOs, Business Associations, Schools / colleges, Neighbourhood associations) should be encouraged to take ownership in events.

Unified Command

A Unified Command allows agencies with different functional authorities, roles, and responsibilities to work together effectively without affecting individual accountability. Under a Unified Command, a single, coordinated Incident Action Plan will direct all activities. The commanders at Incident Response System will supervise a single Command and all stakeholders will seek same purpose in conducting emergency operations.

Risk Analysis and Preparedness

The first aim of any Crowd Management process is to prevent serious situation from developing. Disasters may often be prevented from happening through careful identification of causes / threats and assessing risks posed by them.

Identify threats / causes

Planners can draw upon wealth of existing information to identify range of threats/causes of disasters at given place of mass gathering. The planning team members should share their own knowledge of threats the venue and its surrounding community has faced in past or may face in future and work with SDMA/DDMA to get information regarding potential threats / causes in community that can cause a disaster

Risk Assessment and Planning

Once potential threats/causes of disasters are identified, their risk should be assessed. Assessing risk should involve understanding probability that specific potential threat / cause will occur; its effects and their severity; time visitors need to be warned about threat; and how long threat may last. A site assessment may include review of site access / exit; structural integrity of buildings; compliance with applicable architectural standards for access; emergency vehicle access.

Information Management and Dissemination

The review of past disasters indicates that in absence of necessary information, people may slow down / panic; change their direction during their movements leading to undesired flows and / or undesirable behaviour. While absence or poor information management in itself can be source of crowding, appropriate information and its dissemination can be useful weapon in managing crowds. Communicating with visitors and providing them with correct information is very critical in all situations - normal, disaster / emergency and disaster recovery. Similarly, timely information exchange between various stakeholders viz. event management, government administration, security agencies, NGOs, media and local population will go long way in ensuring that crowd gathering events run smoothly without any untoward incidents

Safety and Security Measures

It is postulated that most of these incidents are avoidable by deploying various safety and security measures.

Emergency Medical Services

Although it is commonly known that immediate medical attention after fatal incident can save lives; presently, there is no official requirement or standard for first aid rooms and on-duty medical personnel at places of mass gatherings. Hence some of event/venue managers avoid/postpone investments in medical services/staffing infrastructure to save their funds. The shortage of medical, paramedical, public health professionals adds to woes of others. As a consequence, medical preparedness is one of weakest links in crowd disaster management. The need is to develop mechanism for awareness creation, ensure availability of trained first-aid staff, kits, ambulances, mobile hospitals/teams, hospital disaster management plans and addressing concerns in public health.

Transportation and Traffic Management

Consideration of available transport facilities, parking and traffic flow is very important in event site selection, crowd control, and also in emergency evacuation. The guiding principles in transportation and traffic management are a) To use public transport as much as possible, b) To minimise impact of undesirable crowd and traffic.

Execution of Plan

Incident Response System (IRS) in General

Efficient functioning of command and control is single most important component of Crowd Management. As per best laid out practices, command and control should have unity and chain of command with built in organisational flexibility, manageable span of control, an integrated information management and communication system, media management and personal accountability.

Analysis of various disasters, including crowd disasters, clearly brings out that there are a number of shortcomings like —

a) Lack of orderly risk assessment and systematic planning process

b) Unclear chain of command and supervision of response activity

c) Lack of proper communication plan and inefficient use of available resources.

d) Lack of predetermined method / system to effectively integrate inter-agency requirements into disaster management structures and planning process.

e) Lack of accountability because of ad-hoc nature of arrangements and no prior training for effective performance by first responders.

f) Lack of coordination between first responders and individuals, professionals and NGOs with specialised skills during response phase

To overcome these deficiencies, especially in response system, NDMA (2010) has come out with Guidelines on Incident Response System (IRS). These guidelines emphasise

a) Systematic and complete planning process

b) Clear cut chain of command

c) System of accountability for incident response team member

d) Well thought out pre-designated roles for each member of response team

e) Effective resource management

f) System for effectively integrating independent agencies into planning and command structure without infringing on independence of concerned agencies

g) Integration of community resources in response effort and

h) Proper and coordinated communications set up.

It is important to acknowledge that all disasters are local events as they take place within boundaries and jurisdiction of local government body and therefore, entire planning and response starts with local capabilities and resources which may later be augmented by community and external resources. Based on magnitude and nature of disaster, Mobile Command Post may be setup in addition to Emergency Operations Centre.

Emergency Operations Centre

The establishment of Emergency Operations Centre, which in a way is nerve center, is mandatory due to likelihood of occurrence of disaster that can take place due to crowding. The main functions are a) data collection and analysis, b) make decisions to save life and property and c) disseminate decisions. This center should be established at prominent location with high visibility so that it can initiate immediate action in case of any eventuality.

Integrated Computer Systems

It is observed that, while computers have been deployed at various route points to control crowd, they currently work as standalone systems. For example, visitor registration slip generated by computer system at entrance of venue may not be read by a) computer connected to bar code scanner at security check post on way to main venue or b) computer system which assigns group number to visitors before their release to main venue. In absence of integrated information system, it is not possible to ascertain whether visitors with particular registration slip have arrived at venue, which could be useful in case of unfortunate catastrophes or for insurance claims. This also prevents organisers from being able to collect vital statistics like average time taken by visitors from registration counter to check post to main venue. Such measurement system is needed to monitor and control crowd movement in efficient and effective way.

Online registration and Registration database:

A lot of places of mass gatherings have started online registration of pilgrims. This registration process could be used to influence arrival pattern. It is desirable to have registration of all visitors. A database system should be deployed to capture demographic details of visitors. The mandatory registration of visitors is an extremely important step in input control in queue management.

Deployment of new age identification tags:

The temple boards / event managers should seriously consider use of bar-coded bands, RFID tags or biometric smart cards instead of traditional paper slips. These tags will carry basic information of visitors. As visitors move through the system, scanners deployed at various locations could be used to keep track of their movements along with timings. This can also help track exact number of visitors at various locations and can further enable better control of traffic flow along the route.

Geographical Information Systems

Geographical Information Systems (GIS), wherever possible, should be deployed in location planning, layout, alignment of roads, structural assessment of parking lots, helipads, laying utility lines etc. It can also be used to determine hazard location, space management, and determination of evacuation paths.

Closed-Circuit Television Camera

Closed-Circuit Television (CCTV) cameras should be deployed for surveillance and early detection of emergency. A central control room should be setup to observe critical hazard points including entry / exit gates, bottlenecks, narrow stretches, parking lots etc. at venue. The typical indicators in crowd monitoring are space between people, number of people in hazard area, Crowd build-up in an area, Crowd behavioural changes. More advanced cameras have motion-detection features which are important from crowd management point of view. The control room should be appropriately staffed by trained personnel. It is also essential to clearly state trigger and action points for various values of crowd density and accelerating movements. A direct communication link should always be available between central control room and security personnel deployed in the vicinity of CCTV cameras.

Image processing

The advances in image processing technology along with CCTV stream are going to see more and more usage in crowd management practices. Systems have been developed by researchers for real time analysis of crowds to detect possible emergency. Typically, these systems have methods to determine crowding situations and corresponding plan of actions. The crowd density and accelerating movements are determined using object characterisation. The complete path network, generated using location plan, positioning of barricades, obstacles, entry/exit points, is then used to determine shortest evacuation plan using GIS. A development of real time crowd monitoring using infrared thermal sequence has also been reported. Forward Looking InfraRed (FLIR) cameras are deployed and software modules developed for determining crowd density.

Crowd Simulation

A number of crowd simulations have been developed recently to a) Evaluate capacity of venue / holding area, b) Evaluate various crowd evacuation strategies, c) Evaluate and compare flow control strategies, d) Estimate evacuation time, e) Estimate crowd density and force at entry / exit gates / barricades.

Crowd Control Science

A typical project involves using off-the-shelf software programs to identify potential bottlenecks in a particular environment, such as stadium or railway station. These models specify entry and exit points at location and then use “routing algorithms” that send people to their destinations.

Public Address System:The Public Address system must be laid out with speakers at all key points along the route. The cabling must be secure and put through conduit properly.

Announcers:Announcers who are well versed with emergency evacuation plans, alternate routes, location of facilities, route map etc. should make announcements in local languages.

Display system (Television):Television must be positioned at various points giving variety of information to people in the crowd.

Base Station with Repeater (Wireless): This system on its own will have range of 2-3 Km only in simplex mode of operation under Line-of-sight conditions. With base repeater station, it will have range of 10-12 km which is desirable and will help contact local police stations / hospitals through wireless on Duplex mode of operation.

These proactive steps will go a long way to save precious human life by preventing Hathras like or similar incidents from occurring.

References:

Ackermann, O., Lahm, A., Pfohl, M., Kother, B., Lian, T.K., Kutzerm, W. M., Marx F, Vogel, T and Hax P-M. (2011) Patient care at the 2010 Love Parade in Duisburg Germany. Deutsch Arztebl int 108, 483-489.

Ahmed, Q.A., Arabi, Y.M. and Memish, Z.A. (2006). Health Risks at the Hajj. The Lancet, 367, 1008- 1015.

Arbon, P. (2007). Mass-gathering medicine: a review of the evidence and future directions for research. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 22, 131–135.

Arbon, P., Bridgewater, F.H., Smith, C. (2001) Mass gathering medicine: a predictive model for patient presentation and transport rates. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 16, 150-158.

Burkle, F.M. Jr and Hsu E.B. (2011). Ram Janki Temple: Understanding human stampedes. The Lancet, 377, 106-107

Deleany, J.S. and Drummond, R. (2002). Mass casualties and triage at a sporting event. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 36, 85-88.

De Lorenzo R.A. (1997) Mass gathering medicine: a review. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine 12, 68- 72

Dunne, L. R. (1943). Report on an Inquiry into the Accident at Bethnal Green Tube Station Shelter on the 3rd. March 1943. Min. Home Security

Elliott, D. and Smith, D. (1993). Football stadia disasters in the United Kingdom: Learning from tragedy? Industrial Environment Crisis Quarterly, 7 (3), 205–229.

Eksborg A-L, Elinder H, Mansfield J, Sigfridsson S-E, Widlund P. (2001). Fire in Gothenburg. 1998 October 29-30. Report RO 2001:02 (o-07/98) by the Swedish Board of Accident Investigation.

Feliciano, D.V., Anderson, G.V. and Rozucki, G.S. (1998). Management of Casualties from the Bombing at the Centennial Olympics. American Journal of Surgery, 176, 538-543.

Fruin JJ (1971) Designing for pedestrians: A level-of-service concept. In: Highway research record, Number 355: Pedestrians. Highway Research Board, Washington DC, 1–15Fruin, J. (1993). The causes and prevention of crowd disasters. In Smith R.A. and Dickie, J.F.(Eds.) Engineering for crowd safety. Dordrecht: Elsevier.

Fruin, J. (1988). Escalator Safety - An Overview. Elevator World, Aug. 42-48.

Garcia, L.M. (2011). Pathological Crowds: Affect and danger in responses to the Love Parade disaster at Duisburg. Dancecult Journal of Electronic Dance Music Culture. p.2; html http://www.dj.dancecult.net/index.php/journal/article/view/66/102.

Grange, J., Baumann, G.W. and Vaezazizi, R.(2003). On-site physicians reduce ambulance transports at mass gatherings. Prehospital Emergency Care, 7; 322-326

Hanna, J.A. (1994). Emergency preparedness guidelines for mass, crowd intensive events. Office of Critical Infrastructure Protection and Emergency Preparedness, Minister of Public Works and Government Services, Government of Canada.

Hsieh, Y., Ngai, K., Burkle, Jr F., Hsu, E.B. (2009). Epidemiological characteristics of human stampedes. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness, 3, 217– 223.

Hsu, E.B. (2011). Human Stampede: An Unexamined Threat. Emergency physicians Monthly 2011. Available from: 〈http://www.epmonthly.com/ features/current-features/human-stampede-anunexamined-threat/〉.

Isobe, M., Helbing, D. and Nagatani, T. (2004). Experiment, theory, and simulation of the evacuation of a room without visibility. Phys Rev E, 69:066132

Johnson, N. R. (1987). Panic at ‘The who concert stampede’: An empirical assessment. Social Problems, 34, 362–373.

Juffermans, J. and Bierens, J. (2010). Recurrent medical response problems during five recent disasters in the Netherlands. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 25 (2), 127-136.

Lovas, G.G. (1998). On the importance of building evacuation system components. IEEE Transport Engineering Management, 45, 181–191.

Lund, A., Gutman, S.J., Turris, S.A. (2011). Mass gathering medicine: a practical means of enhancing disaster preparedness in Canada. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine 13, 231–236.

Martin, T.E. (1990) The Ramstein Airshow Disaster. Journal of Royal Army Medical Corps Vol. 136, pp.19-26

Milsten, A.M., Maguire B.J., Bissell R.A., Seaman K.G. (2002). Mass-Gathering Medical Care: A Review of the Literature. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 17, 151-162.

Miller, D.L. (1985). Introduction to collective behavior. Belmont: Wadsworth.

Mollen, M. (1992). - A Failure of Responsibility - Report to Mayor David N.Dinkins on the December 28, 1991 Tragedy at City College of New York. Jan. 1992. Moddie, M. (2004). Accidents and Missed Lessons. Frontline, 16, 13-14.

National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). Accidental Deaths & Suicides in India—Annual Publication. New Delhi: Ministry of Home Affairs. Government of India. 〈http://ncrb.nic.in/index.htm〉.

National Disaster Management Authority (2014). A Guide for Administrators and Organisers of Events and Venues.

National Disaster Management Authority (2010). National Disaster Management Guidelines—Incident Response System.

Ngoepe Mr Justice B. (2001) Final Report Commission of Inquiry into the Ellis Park Stadium Soccer Disaster of 11 April 2001. http://www.info.gov.za/view/DownloadFileAction?id=70241

Olapade-Olaopa E.O., Along T.O, Amanor-Boadu S.D., Sanusi, A.A., (2005). On-site physicians at a major sporting event in Nigeria. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 21, 40-44.

Popplewell, Mr Justice O. (1986). Committee of Inquiry into Crowd Safety and Control at Sports Grounds. Final Report. Cmnd 9710 Jan. London, HMSO.

Pozner, V. (1990). Parting With Illusions. Atlantic Monthly Press.

Report of the Tribunal of Inquiry on the fire at the Stardust, Artane, Dublin on the 14th of February 1981. By Tribunal of Inquiry on the Fire at the Stardust, Artane, Dublin on the 14th of February 1981 (Ireland) Published in 1982, Published by the Stationary Office (Dublin). http://www.lenus.ie/hse/bitstream/10147/45478/1/7964.pdf

Sanders A., Criss, E, and Steck, l. (1986). An analysis of medical care at mass gatherings. Ann Emergency Medicine, 15, 515-519.

Soomaroo, L. and Murray, V. (2012). Disasters at mass gatherings: lessons from history. PLOS Currents Disasters, 4, RRN1301.

Still, G.K. (1993). New computer system can predict human behaviour response to building fires. Fire, 84,:40–41

Still, G.K. (2000). Crowd dynamics. Ph.D. thesis, University of Warwick

Takashi, Y., Ishiyam, S., Yamada, Y. and Yamauchi, H. (2002). Medical triage and legal protection in Japan. The Lancet 359, 19-49.

Taylor, Lord Justice. (1990). Final Report into the Hillsborough Stadium Disaster, CM 962. London, HMSO. The Hillsborough Stadium Disaster. Interim report Aug. 1989, HM Stationery Office., pp 71.

Weir, I. (2002). Findings and Recommendations by the Coronial Inquest into the Death

Thompson PA, Marchant EW (1993) Modelling techniques for evacuation. In: Smith RA, Dickie JF (eds.) Engineering for crowd safety. Elsevier, Amsterdam, 259–269

Treuille, A., Cooper, S. and Popovic, Z. (2006). Continuum crowds. ACM Trans. Graph. 25 (3), 1160– 1168

Wertheimer, P. (1980). Crowd Management- Report of the Task Force on Crowd Control and Safety. City of Cincinnati, July 1980.

World Health Organisation. (2008). Communicable disease alert and response for mass gatherings: key considerations. Technical Workshop. June. Available from: 〈http://www.who.int/csr/mass_gathering/en/print.html〉.

Zhen, W., Mao, L. and Yuan, Z. (2008). Analysis of trample disaster and case study - Mihong bridge fatality in China in 2004. Safety Science, 46, 1255-1270.