Abstract:

Maritime cyber security involves action plans for national governments for governing the terrain of cyber space with necessary tools, policies, agencies, threat and risk management plans, technologies, intelligence, and everything else that a government deems fit and advocates to protect the ocean property regime of the nation to maximise the yield towards integrated national security. The government will need specific agencies for it. This paper briefly examines the subject and advocates capable coast guards to be entrusted with the task based on their charter for maritime law enforcement and services in addition to other tasks in the national interests. In this attempt the paper begins with a few imaginary scenarios to highlight the seriousness of the problem at international and national level. It concludes with an affirmation recommending coast guards as the prime agencies for integrated maritime cyber security for consideration by national governments unless there are other competent agencies identified according to strategic national security.

Key words: National security, maritime security, cyber security

Preamble:

Imagine scenario #1. A cruise liner entering a busy harbour at night. Two mandatory harbour pilots on board alongside ship’s Captain standing alert with the crew on ship’s bridge. Entire crew on watch at various stations around the ship on alert for precision manoeuvre under a traffic laden bridge. Suddenly the ship loses power turning ‘not under command (NUC)’. The vessel moves uncontrollably as if guided towards one of the pillars of the bridge and collidesunder tremendous force of momentum. The entire bridge collapses in seconds into the water. Could it be a typical case of targeted attack, where ship’s power systems were first beset, subsequently controlling steerageway using cyber tools to head on to the nearest supporting pillar of the bridge using the massive ‘extended yards-per-knot momentum’? Is it possible when a ship’s systems are highly integrated, but poorly defended?

Imagine scenario #2. Port operations come to a standstill without warning. Authorities are in total bedlam as their commitments towards shippers and vessel operators get stalled abruptly. Port is closed for traffic. Investigations reveal cyber-attack on the port’s web system spread into the internal computer systems. On the third day the port gets a demand for ransom lest the attackers should release sensitive stolen data on the dark net or pass on to those in demand of information leading to information traffic.

Imagine scenario #3. A classification society finds ransomware attack on its software. 30 percent of its fleet operating around the world get affected. Its network is knocked off-line.

Imagine scenario #4. The entire cyber server of an authority located undersea for better cooling, safety and security gets heated up by induced thermal flux by dark hackers. Data is the target. The man-in-the-middle (MITM) attack disrupts communication between the server operator and the user besides burning off ‘server data.’ Impact is on cryptosecurity. The cryptographic protocol is breached. The cryptographic client-server parameters are compromised. Over and above, corrective action for physical protection of the underwater server array gets delayed by spatial limitations and absence of response plans.

Imagine scenario #5. The shipping world is seriously negotiating induction of autonomous ships for considered and acceptable reasons. The question, what if they fall prey to maritime pirates cannot be answered at this stage as they could be targets for conventional as well as cyber piracy attacks at the same time. The need for automating for physical protection of the ship and cargo will require equal importance for techno-regulatory feasibility along with all other operational phases. It is not feasible today but can be automated in course of time on a priority track.

Introduction

National security is the prime objective of national governance. Hence, an ever-changing concept as human systems evolve. The concept has evolved from mere physical security of a nation towards maximising by optimisation of human well-being by governance. The turn around came when a group of undergraduates in Yale University expressed economic factors in addition to military factors as the second element of national security governance in 1789(2). Today the concept of national security stands for more elements according to practitioners and researchers as appreciated by them.

The elements of national security are mutually inclusive. The job of governments today is to optimise them to maximise human well-being. Optimising the elements of national security alone will not suffice. Today’s governments will have to operate on different terrains, beyond the land, which is the home ground for humans. Some are physical and some non-physical. There are eight such terrains as identified by the author by research(3). Maritime cyber security, where cyber security is an element of national security, operates on two terrains: the ocean, a physical terrain, and cyberspace, a virtual terrain. They have to be integrated mutually and, thereafter, with the overall national security primary terrain for the land based human system governance. A mathematical model for developing national security policies related to ocean and cyber space for integrating with national security will place such demand in front of any government. The elements and terrains independently as well as mutually do not stand alone in national security strategy. They are mutually inclusive. It is within this template a nation has to examine its national security strategy under strategic national security principles and govern as it deems fit.

Defining maritime cyber security

It is important to examine the overall strategic national security policy of a government for defining maritime cyber security. There are many definitions for national security. They can still change. Accordingly elemental and terrain specific definitions too can change. The author defines national security as the measurable state of the capability of a nation to overcome the multidimensional threats to the apparent well-being of its people and its survival as a nation state at any given time, by balancing all instruments of state policy through governance, that can be indexed by computation, empirically or otherwise, and is extendable to global security by variables external to it(4).

The definition of maritime security thus stands corollary to the definition of national security as the all-encompassing complementary faction of national security of a maritime nation from an ocean specific terrain assessment applicable to that nation(5). For this, every nation in the world is considered a maritime nation by virtue of the ocean belonging to the global commons barring specified limitations under the Law of the Sea Treaty commonly called the UNCLOS (United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea). Every nation is affected by the World Ocean.

Cyber security is the 14th identified element of national security in the chronological hierarchy of 16 elements (Paleri, 2022)6. It is about managing and governing the cyber space, the sixth terrain of national security, to the best advantage of the people. It is not strictly cyber system security, but a whole element of national security in the cyber space related to information that needs governance in tandem with other elements for maximising national security.

Maritime cyber security, therefore, can be defined as the cyber security that impact maritime security in the overall governance by national security (GBNS) of a nation or similar geostrategic entity(7). The definition can change based on the proponents’ perceptions. Basically, in this paper, it leads us to examine the ocean-based interests of a nation that are to be integrated and safeguarded by national interests. These interests can be consolidated under the concept of ocean property, (Paleri, 2002), with its four constituent elements and modelled for governance as desired by the government.

Ocean property

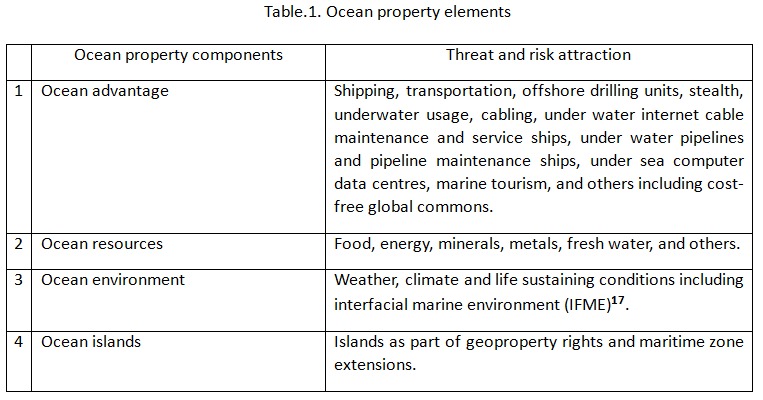

Global ocean is a unitary entity. It has been divided into various divisions for convenience of governance. As brought out earlier, the World Ocean is a global common barring the property rights under international law that are limited compared to the expanse of the ocean that is ever changing. But the fact remains ocean is an extension of land under water that has identified and accepted characteristics(8). Every nation, whether landlocked, coastland, or island(9), (Paleri, 2017) is a maritime nation that can claim ocean property(10) similar togeopropertyrights(11). Every nation as a maritime nation can enhance its net worth by adding the ocean entitlement, the ocean property available to it, which in earlier times was roughly estimated and termed as ocean wealth(12). The ocean property of any country comprises four components as identified in varying gradations that add to its net worth and can be mapped for quantum modelling:

1. Ocean advantage.

2. Ocean resources.

3. Ocean environment.

4. Ocean islands.

The elements of ocean property are also interconnected and not isolated in maritime security modelling. Hence optimising ocean property is inclusive of the overall governance by national security. The four components of ocean property can be modelled by linear programming (operations research) and other methods for developing overall integrated national security strategy. Threats to ocean property of a maritime nation can affect its national security. Maximising ocean property by optimising the components is the objective of the maritime security governance of a nation. The quantum of ocean property will vary for each nation. The objective is maximum gain out of ocean property. One of the threats to ocean property and all that associated with it comes from the cyber space. This is where maritime cyber security encounters and clears a significant way point in the fast-evolving global system. It is a serious matter.

Cyber security impact on ocean property

Strategic national security(13) demands high level research in all relevant fields associated with the elements of national security and its terrain specificity. In maritime cyber security, it can be separated prior to integration into the ocean property regime. In this process the charters of the coast guards or the appropriate national maritime agencies are limited to the respective national interests unless called for information sharing with interactive agencies. Coast guard is just one of the agencies in the maritime domain. There are 129 coast guards as identified by the author in a study in 200914. While the charter of the coast guards of the world are more or less uniform as law enforcement and services, and other duties in the respective national interests, they perform them under country specific motives in varying degrees. They support the policies of their respective countries and assume structural characteristics accordingly. The primary job of any government is rule of law (ROL) under domestic and international laws.

Optimisation of ocean property rights for maximisation of national security, therefore, will be in national interest of respective governments. Accordingly, the cyber security aspects under ocean property regime will be based on demands of each component of ocean property as mapped and appreciated periodically. The cyber security norms in the maritime space have to be shored up by the appropriate agency of a nation. It is the choice of the concerned nation. But the coast guards, being accountable to the charter for law enforcements and services, could be leading a nation in maritime cyber security since it is applied to rule of law in maritime space. The functional charter of the coast guards on the rule of law and the good order and discipline of the ocean is the closest to ocean property and ocean property regime of a nation. The coast guards may, therefore, develop strategic plans of action for maritime cybersecurity. That is the ideal situation. But many coast guards will not have the capacity and capability for leading maritime cyber security. It is a choice for them and their governments. The earlier, it will be better. Otherwise, they will find it difficult to catch up when the situation demands as it is a highly evolving and demanding discipline. The scenarios highlighted in the beginning of the papers are indicative.

There are already specific agencies in various nations for cyber security. The mission of the United States Coast Guard Command is to defend the coast guard cyber space, enable coast guard operations in all select terrains—land, ocean, air space, outer space and cyber space—and protect maritime transportation systems. The Maritime Transportation Security Act (MTSA), 2002 requires the US Coast Guard (USCG) to regulate and enforce physical security across ports, facilities and vessels. US coast guard being the agency for marine safety in relation to shipping could lead the way towards the ultimate cyber secure maritime transportation system (CSMTS),

(Maheshwari, 2023)(15).China has recently launched (19 April 2024) the Information Support Force (ISF) as a new wing of Peoples’ Liberation Army (PLA); it is reported(16). The ISF is considered to be the revised version of PLA’s Strategic Support Force (SSF) since 2015 in informationised wars. It is not exclusively for the maritime terrain but will function as per the prevailing PLA doctrine in which the Chinese Coast Guard is an active participant. Most of the countries have much to catch up in the quest for maritime cyber security.

The command centres are primarily based on national interests as envisaged by respective countries. None of them use the conceptualised ocean property regime but its variants as felt appropriate by the respective governments. Nations in general when focusing on maritime cyber security may find it effective if the ocean property elements are considered for threat and risk elimination through cyber security operational strategies. The ocean property related threats can be challenging in both ocean governance and establishing rule of law at and from the sea if the governments map and assess the elements periodically to know the exact net worth of their maritime terrain. Each component of ocean property comprises various factors; some more may evolve further (Table 1).

Coast guard perspective

Nations that have effective coast guards could be a good choice for governments to consider as coast effective lead agencies for maritime cyber security. Coast guards are generally considered non-adversarial. They are meant to establish rule of law at and from the sea besides providing services such as search and rescue, environmental protection, scientific assistance, etc. under their charter. The ocean property elements are also supportive for maritime crimes and other unlawful activities at and from the sea. Hence it is more important that maritime cyber security authority is delegated to the national coast guards or similar maritime law enforcement agencies where they exist.

The coast guards, if designated as cyber security enforcement agencies in the maritime terrain, should develop dedicated and overarching cyber strategy for supporting national security interests. They should have the capacity to work with national cybersecurity system and agencies. They should be accountable to the respective national governments for maritime cyber security. The coast guards authorised as national agencies for maritime cybersecurity should be able to work in close contact and rapport with port facilities, vessel operators, other agencies such as customs, shipping authorities, fisheries, military, intelligence, marine environmental agencies, forensic investigators, and a host of others nationally and internationally. They must plan cyber security strategies and ensure cyber hygiene in the concerned maritime fields. More than anything, the coast guards should be ready to accept the task and jump start as for most of the coast guards it will be the beginning of a new task though very much within their legal charter.

In this effort the coast guards will have to find new partners and familiarise with them in a collective and participatory role. They are used to collective and joint operations. Jointness is an advantage the coast guards have. They have to work with all stakeholders in cyber security in relation to the maritime terrains. Their numbers will increase in course of time.

The threats and risks associated with cyber-attacks towards national and global infrastructure are grave. It impacts on all components of ocean property in establishing comprehensive maritime security and its integration with national security. Protecting national interests in its ocean property, needs competent organisations and national agencies including those dealing in maritime intelligence, regulatory norms and adjudications systems. Frontliner coast guards could be made effective maritime cyber security agencies by their charter by forward thinking governments.

Conclusions

The maritime scenario under the concept of integrated national security is fast changing. Within the strategic space available for national governments, cyber security poses significant challenge to ocean property governance. There should be appropriate agencies to handle such a challenge. The coast guards, if capable, are ideal agencies for rule of law and services in the maritime terrain for any government. National security conscious nations may focus on coast guards and make them capable of working with all stakeholders under their maritime charter. This will call for high magnitude efforts in strategic planning on the part of the coast guards on maritime cyber security. It may even change their public image in the evolving world in deterring cybercrime and other unlawful activities in the ocean terrain. In this task they should also be acceptable to all stakeholders as an agency that can deny latent cyber attackers. It is also an imperative that the coast guards in addition to capacity building, strengthen their intelligence gathering capabilities for decision advantage against possible cyber adversaries.

End Notes:

2. Romm, J.J. (1993). Defining national security—non-military aspects. Council of foreign relations press. P.15.

3. Paleri, P. (2022). Revisiting national security: prospecting governance for human well-being. Springer.

4. Paleri, P. (2002). ‘The concept of national security and a maritime model for India.’ Multidisciplinary Doctoral dissertation. Department of defence and strategic studies, University of Madras, India.

5. Ibid.

6. Paleri, n.2.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. Paleri, P. (2014). Integrated maritime security: governing the ghost protocol. Vij Books.

10. Paleri. n.3.

11. Demarest, G. (1998). Geoproperty: foreign affairs, national security and property rights. Frank Cass.

12. A parallel (though time impacted) can be drawn with reference to the ancient Indian term Samudra manthana (churning the ocean) (also called sagaramanthana, kshirasagaramanthana, and amrita manthana depicted in the text Vishnu Purana (date contested). The text mentions about the value of the ocean, its yield and rights of all on the yield when churned together. Ocean property is about the rights of a nation associated with its ocean that a government can maximise for integrated national security while governing by national security (GBNS).

13. Paleri. n.2.

14. Paleri, P. (2009). Coast guards of the world and emerging maritime threats. Ocean policy research foundation, Tokyo. The study showed 127 coast guards in 2009. The present Sri Lanaka coast guard was inaugurated on 4 March 2010 and Kenyan coast guard (Linda Tufaulu) in 2018.

15. Maheshwari, R. Cyber threats in maritime transportation. Research dissertation for the award of LL.M. in coastal and maritime security law and governance, School of Integrated Maritime and Security Studies, Rashtriya Raksha University, Lavad, June, 2023.

16. ‘President Xi launches information support force for Chinese military, a new wing to fight cyber wars.’ https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/president-xi-launches-information-support-force-for-chinese-military-a-new-wing-to-fight-cyber-wars/articleshow/109441027.cms?from=mdr. Accessed 20 April 2024.

17. Paleri, P. (2009). Marine environment and peoples’ participation. Knowledge World International.

References:

Kesseler, G.C., & Shepard, S.D. (2022). Maritime cybersecurity: a guide for leaders and managers. (2nd ed.).

Roberts, F.S., & Drumhiller, N.K. & DiRenzo III. J. (Eds.). (2017). Issues in maritime cyber security. Westphalia Press.

Singh, P.K. (Ed.). (2018). Combating cyber threat. Vij Books.

Akpan, F.: Bendiab, G.: Shiaeles, S.; Karemperidis, S.; Michaloliakos, M. Cyber security challenges in the maritime sector. Network 2022, 2, 123-138, https//doi.org.10.3390/ network2010009. Accessed 11 April 2024.