Abstract:

The advent of air power significantly changed the use of force bringing a wide range of options for deterrence and imposing punitive measures. The Indian Air Force (IAF) is the primary and most potent repository of Indian air power. It remains our principal deterrent against a combative China. However, in the Indian national security discourse, air power has been generally downplayed and not understood well by the strategic community. China, India’s primary threat, has methodically built its air power, causing a serious disparity in force levels, upsetting the India-China air power balance and eroding our deterrence. This article examines the present state of Indian and Chinese air power and a decade hence. The emerging pattern is not an optimistic one for India unless serious and strong steps are taken in a ‘mission mode.’ The article suggests steps to reverse the precipitous decline in Indian air power as well as enhance its awareness, understanding and stature in the national security calculus, strategic community and academia.

Introduction

War and the use of force have historically been the most important and arguably effective instruments of power projection. This was true even before the Westphalian system was adopted by much of the West. Strife, violence and force to impose the will of one entity over another has continued unabated even after the Treaty of Westphalia, numerous regional and the two world wars. The misery, suffering, death and destruction caused by the world wars gave rise to ‘peace’ movements worldwide. However, every entity, including nation-states, realised that to attain peace, they were required to possess powerful armies and navies. Thus, the term ‘hard power’ as we know it today manifested through military power assumed great importance. Military power till the twentieth century comprised armies and navies. The first human flight in 1903 and the subsequent ‘weaponisation’ of an aeroplane gave birth to the third and most impactful dimension of hard power in the form of air power. Just eight years after the flight by the Orville brothers, offensive use of air power came to the fore in the Turkish-Italian War of 1911. This was the first instance when a bomb was dropped from the air. It was also the beginning of a new era in warfighting that soon witnessed air power's increasing potency and influence on national security and international relations. Even before World War I (WW I), such was the fear of being attacked from the air that the Church in England banned the overflight of aircraft and gliders! Early proponents of air power, such as Billy Mitchell, Lord Trenchard, and GulioDouhet, propounded theories on air power. These generated considerable debate and disbelief from the predominantly land and maritime-centric defence establishments. However, the role of air power in World War II (WW II), through the Cold War and thereafter, is evidence of air power maturing into a unique and distinct yet complementary domain to the traditional ones of land and maritime.

Although the British created the Indian Air Force (IAF) in 1932 for their own needs, India was fortunate to have an independent air force even before many other countries, including the U.S. The crucial and valiant role of the IAF in WW II earned it the title of ‘Royal’ in 1945, and it became the Royal Indian Air Force (RIAF). The RIAF was put into action within two months of independence, and its action of airlifting troops into Srinagar ensured Kashmir remained a part of India. In the nearly 79 years of our independent existence, Indian air power has grown and evolved considerably. Globally, air power trends have been significantly influenced by technology, adding to its lethality and versatility. No wonder air power is often the first option nations look to in a crisis and often one that brings timely, decisive results.

Understanding Air Power

Before proceeding further, it is extremely important to understand what air power is. In simple terms, air power can be understood as the total ability of a nation to use/exploit the medium of air for its interests. Constituents of a nation's air power include a dedicated (and independent) Air Force, the air arms of the Navy, Army and Coast Guard, and civil air resources (civil airlines and operators registered in India). An Air Force can employ air power to prosecute all the air and surface operations, differentiating it from the other services' air arms. This unique ability of the Air Force is reflected in its structure, technology, organisation, training and infrastructure(1). A widely prevalent myth is that air power is essentially fighter aircraft. Nothing is further than the truth. The platforms undertaking offensive missions are not just limited to fighter aircraft. Historically, the IAF has employed transport aircraft and helicopters in offensive roles. Mi-4 helicopters in the Indo-Pak war of 1965, An-12 transport aircraft in the 1971 Indo-Pak war and Mi-17 helicopters in the Kargil conflict are some notable examples. However, fighter aircraft's reach, speed and weapon-carrying capability make it the platform of choice for offensive missions.

Another myth arose, especially after the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict and the Russia-Ukraine war. Citing the examples of these wars, in which Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS) and Surface-to-Air Guided Weapons (SAGW) have garnered headlines, some analysts have written the obituary of manned aerial combat. Elon Musk created a stir when he said, “The fighter jet era has passed” at a USAF Air Warfare symposium(2). Historically and doctrinally, it is proven that a balanced air force requires adequate fighter aircraft, a good airlift capability manifested through transport aircraft, and a ubiquitous ability through helicopters. The successful conduct of air operations requires ‘enablers.’ These combat enablers are platforms such as Flight Refueling Aircraft (FRA), Airborne Warning and Control Systems (AWACS), Electronic Warfare (EW) aircraft and special operations aircraft. Professional air forces realise the need for an offence-defence balance. Hence, they also invest in a robust, redundant, resilient Air Defence (AD) system. Constituents of such a system include a network of radars, a reliable communication system and weapons such as AD fighter aircraft and SAGW. Missile technology, delivery, and accuracy improvements have seen nations augmenting their offensive strike capability through ballistic, cruise and hypersonic missiles. Lately, there has been an effort towards developing a Ballistic Missile Defence (BMD) as part of the overall AD system. Simultaneously, developments in aircraft technology have birthed stealth aircraft. The ‘cat and mouse’ game thus continues. At the same time, there is no denying that UAS have added a new dimension to the air war. But to write the obituary of manned fighters, as Elon Musk remarked, is not just incorrect but outrightly dangerous.

Air power is highly dependent and influenced by technology, requiring good, well-educated, skilled, and competent human capital to absorb technology. Air power also requires an innovative, competitive, adaptable industry that can scale up production if the situation demands it. The characteristics of air power, such as flexibility, lethality, responsiveness and trans-domain capability, offer multiple options. Still, these depend upon secure bases from which platforms can operate and be maintained. This demands considerable investment in infrastructure such as airfields, Hardened Aircraft Shelters (HAS), and Command, Control and Communications (C3) networks and their maintenance. The ‘front-end’ of air power showcased primarily in its flying platforms has to be ably supported by the ‘back-end’, i.e. maintenance and administration, to ensure its effectiveness.

Present Composition of Indian Air Power

The article will now focus on the military component of Indian air power. As the largest repository of air power, the focus will primarily be on IAF. For the sake of brevity, only major weapon platforms and systems will be analysed. There has been considerable discussion in the media about the shortage of fighter squadrons in the IAF. In 2000, the IAF presented a Vision 2020 to the Government of India (GoI), recommending 55 fighter squadrons. In 2012, GoI accorded sanction for 42 fighter squadrons to be raised by the end of the Thirteenth Plan period, i.e. 2027(3). Between 2008 and 2013, the IAF fighter squadron strength was approx. 37(4). However, ever since, it has been a precipitous decline, and the present number stands at 31. Typically, a fighter squadron has 18 aircraft, of which two are trainer versions. Hence, as against a sanction of approximately 750 aircraft, the IAF has to make do with approx. 550. The mix of fighter aircraft varies from the obsolescent Mig-21 to the modern Rafale. Around half the aircraft are of the 4th generation (or Gen 4). These comprise the Su-30 MKI, Tejas and Rafale (Gen 4.5).

The IAF transport (airlift) fleet is in a reasonably sound state thanks to the visionary decisions taken in 2008 and 2011 to purchase the C-130J and C-17, respectively. The C-130J induction in 2011 was followed by the C-17 in 2013. Today, almost a dozen each of these worthy platforms adorn the IAF colours and continue to earn accolades all over the globe, be it for Humanitarian Assistance & Disaster Relief (HADR) or aerial diplomacy. The older fleet of IL-76 aircraft was inducted in the 80s, and after a limited mid-life upgrade, their service was extended till 2035. A report has suggested that the IAF has approached Russia to extend the life of these aircraft till 2050(5). In the FRA category, the present number of six IL-78 is inadequate and beset with serviceability challenges. A Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) report in 2017 observed that the average serviceability of this fleet from 2010 to 2016 was just 48.51 percent(6). While the present status is unknown, the dependency on spares from Russia continues. The persistent efforts of the IAF to procure the Airbus A-330 Multi-Role Tanker Transport (MRTT) have twice failed due to lack of govt. sanction. Hence, it would be fair to assume that challenges in FRA persist. The backbone of the medium-lift fleet remains the 100-odd An-32 aircraft procured in the 80s. These, too, would require replacements in the coming decade. The oldest transport aircraft in our inventory is the Avro, procured in the 60s. Albeit delayed, its replacement by the C-295 is underway. The light transport fleet comprises the Do-228.

The helicopter fleet has been recently bolstered with the induction of Apache attack helicopters and Chinook heavy-lift ones. The Light Combat Helicopter (LCH) ‘Prachand’ induction has commenced and will add to the attack capability, especially in high-altitude areas. The Light Utility Helicopter (LUH) is delayed; hence, the aged Chetak and Cheetah helicopters continue to provide yeoman service. The Mi-17 and Dhruv form the backbone of the medium-lift capability.

In the SAGW segment, the IAF has a mix of short-range (Igla), medium-range (Akash, Pechora, OSA-AK) and long-range (MRSAM, S-400) missiles. The Pechora and OSA-AK are obsolescent and require replacement. IAF has networked and integrated its radars through the Integrated Air Command and Control System (IACCS) to provide seamless coverage. The present fleet of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) comprises a mix of Medium Altitude Long Endurance (MALE) and High-Altitude Long Endurance (HALE). However, increasing numbers are called for given the airspace required to be put under surveillance.

The Indian Navy (IN) possesses two aircraft carriers. It has about 40 Mig-29K as the carrier-borne fighter. However, this strength is woefully inadequate for the envisaged tasks at sea. The Navy’s interim requirement for 57 fighters to be purchased ‘off the shelf’ has been curtailed to 26. Approval by the Cabinet Cabinet on Security (CCS) was accorded only in March 2024. The Rafale-M has been chosen, and contractual details, including pricing, are being worked upon. Another glaring deficiency at sea is the lack of a carrier-borne fixed-wing Airborne Early Warning (AEW) aircraft. The induction of P-8 I aircraft for maritime reconnaissance has greatly boosted the surveillance and anti-submarine capability at sea. However, the helicopter fleet is largely old, comprising Chetak, Ka-28, Ka-31 and Sea King helicopters. The only recent additions are Dhruv and MH-60R, but in limited quantity.

China’s Air Power: Current State and Future Trends

The ascendancy of Xi Jinping as President of China has witnessed a rise in China’s aggressiveness on the military and diplomatic front. The People's Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) too, increased its undesirable acts in the air, especially since the outbreak of the COVID pandemic. A total of 2840 PLAN and PLAAF aircraft intruded into Taiwan’s Air Defence Identification Zone (ADIZ) since 2020 and up to December 2022 (7). Last year, a total of 1674 aircraft violated Taiwan’s ADIZ (8). Malaysia was a victim of Chinese aggressiveness when its airspace was violated by 16 PLAAF aircraft on 02 June 2021 (9). According to a report by the Pentagon, between the fall of 2021 and the fall of 2023, over 180 incidents of dangerous air intercepts against U.S. aircraft were recorded (10). These exceeded the total number of such instances in the previous decade. Chinese actions were not limited to the U.S. PLAAF indulged in around 100 episodes of intimidating and hazardous manoeuvres against U.S. Allies and partners in the same two-year period (11). On 04 May this year, a Royal Australian Navy (RAN) MH-60R helicopter operating over international waters in the Yellow Sea was intercepted by a fighter aircraft of the PLAAF. In a dangerous and blatantly illegal act, the PLAAF aircraft released flares across the flight path of the RAN helicopter, endangering the safety of the helicopter and its occupants (12). Between 01 and 12 June this year, Taiwan reported 132 violations of its airspace by PLAAF aircraft (13). A decade ago, such acts by PLAAF were sporadic. China’s belligerence, mainly confined to land and the maritime spheres, has increasingly been displayed in the air.This aggressive behaviour is due to Beijing’s growing confidence in its air power capabilities. Importantly, it is a recognition in the Chinese leadership of the multifarious options that air power brings to the table in situations of ‘No War No Peace’ (NWNP).

The PLAAF and PLA Navy (PLAN) Aviation constitute the largest aviation forces in the Indo-Pacific and the third largest globally, with over 3,150 total aircraft (excluding trainers) (14). While opacity marks Chinese force levels, various estimates place the number of fighter aircraft in the PLAAF at about 2000. Of these, close to 1400 are of the Gen. 4 or above. Unlike the IAF, the PLAAF has long-range bombers in its inventory. These comprise the H-6 family and its variants. These bombers have been equipped with Land Attack Cruise Missiles (LACM), Anti-Ship Cruise Missiles (ASCM) and Air-Launched Ballistic Missiles (ALBM), giving them good stand-off strike capability. In the AWACS/AEW category, China flies the KJ-2000, KJ-500 and KJ-200 aircraft. Five years ago, the PLAAF publicly debuted the Y-9 electronic warfare aircraft (GX-11), whose role is to upset an opponent’s battlespace awareness (15). The PLAAF is rapidly inducting the Y-20 (made from stolen designs of the C-17) heavy-lift aircraft and the world’s largest seaplane, the AG 600. The PLAAF had built a force of 50 Y-20 and 20 IL-76 by the end of end-2022 with more of the former being produced through 2023 and possibly 2024 (16).

China’s emphasis on UAS continues, and recent developments include the unveiling of Xianglong jet-powered UAS, supersonic WZ-8 and a redesigned version of the GJ-11 stealth Unmanned Combat Air Vehicle (UCAV). Efforts continue to develop and refine concepts in autonomous, teaming and swarm capabilities. Any future conflict will surely involve numerous ‘intelligentized’ UAS from the Chinese side. The PLAAF has a large SAGW mix comprising the S-300, S-400 and HQ-9 (and its variants). The indigenous CH-AB-X-02 (HQ-19) will likely have a BMD capability. Developing a kinetic-kill vehicle technology to field a mid-course interceptor to comprise the upper layer of multi-tiered missile defence is underway.

China’s domestic aircraft industry has made significant headway. It can now produce all its Gen. 4 and above fighter aircraft indigenously. China has produced two fifth generation (Gen. 5) fighters- the J-20 and the FC-31 (intended for export). It is possible that the J-35 carrier-borne aircraft could also be in the Gen. 5 category (17). Noteworthy advancement has been observed in developing a sixth generation (Gen. 6) fighter aircraft for the PLAAF, which could be inducted by 2035 (18).

The India-China Air Power Balance

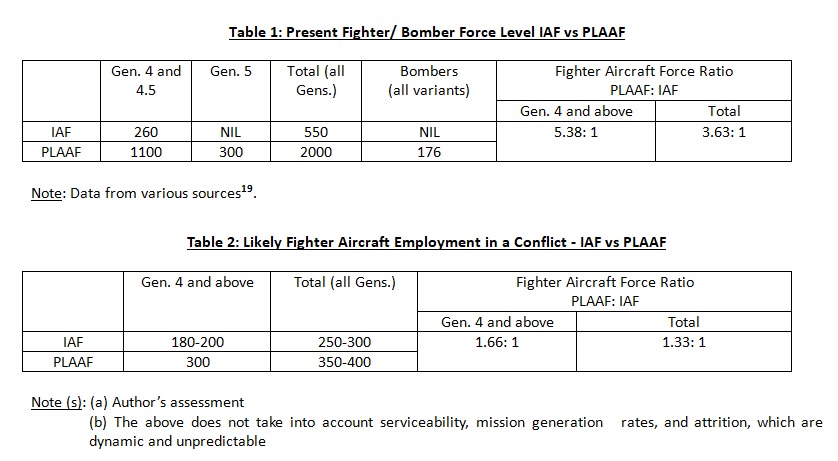

There is a general tendency to resort to bean counting in assessing the power or potential of militaries. Force-level or military hardware gives an idea of a nation’s military strength but is only one measure of its effectiveness. Military power and effectiveness include intangible factors like material/diplomatic support from friendly countries, national strategy, leadership, training, and morale. Even in the tangible factors such as platforms, the quality and quantity vary, as well as their performance in simulated/ actual combat. Another crucial aspect in air operations is the sortie generation rate. It is defined as the number of mission-capable sorties an aircraft can launch in a span of 24 hours. The serviceability of aircraft and the ability to undertake quick repair, replenishment, refueling and rearming decides the sortie generation rate. As explained earlier, the quality and availability of suitable infrastructure, technology and importance given to air power in the national security calculus are important factors. Neither the IAF nor PLAAF can deploy their entire air power capability against each other, given that both have adversaries on other fronts. The tables below depict the present force level and estimate the likely numbers lined up against each other at the outbreak of hostilities.

From the data in the tables above, it is abundantly clear that the PLAAF enjoys a significant numerical advantage over the IAF in fighter/bombers. Except for the two squadrons of Tejas, the rest of IAF’s Gen. 4 and above fighters are imported. Despite the Su-30 being license-produced in India, it is known that India depends upon Russia for many of its components and spares, including aero-engines. The Indo-Russian friendship and past relations cannot guarantee Russia’s dependability to supply spares in an India-China conflict. The geopolitical reality is that Russia and China have a “no limits” partnership. Even expecting Russia’s neutrality in a conflict with China is a tall order, especially since Russia needs China more than it needs India. Since the beginning of the Chinese incursions in Ladakh in the summer of 2020 and India’s riposte, the Chinese have rapidly built and upgraded the airfield infrastructure in Tibet and Xinjiang. It has developed heliports, air defence missile complexes, storage facilities and hardened aircraft shelters. They have also deployed the J-20 in Tibet. These steps have almost neutralised the earlier advantage the IAF enjoyed over the PLAAF. A dense network of radars and missiles has come up opposite India, creating complications for the IAF. Although the payload capability of PLAAF fighters from Tibet is low, the extended runways, a proliferation of airfields (both civil and military), air-to-air refuelling, and the H-6 bombers with long-range stand-off capability aided by adequate enablers/ force multipliers such as AWACS/ AEW makes it a formidable challenge for the IAF to overcome. Adding to the IAF’s challenges is a sub-optimal domestic R&D capability, a weak defence supply chain from Russia and a questionable ability of domestic defence PSUs to ensure timely delivery. Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) can manufacture only eight Tejas annually. It intends to increase production to 24 aircraft by 2026-27 (20). On the contrary, China has been able to produce 300 Gen. 4 and Gen. 5 aircraft like J-10C, J-16 and J-20 annually (21). The IAF will find it increasingly difficult to replace combat losses, while the PLAAF has ever-expanding numbers to replace their losses. Thus, the longer a conflict, the force ratio will increasingly become adverse for the IAF. To avoid such an undesirable state, logistic sustenance, timely weapons replenishment, adequacy of platforms, and war reserves become sine qua non.

IAF Fighter Fleet: A Decade Hence

In all fairness, the IAF has regularly highlighted the worrisome decline in fighter squadrons. The IAF proposal for 126 Rafale was curtailed to a mere 36. The induction of Tejas has been excruciatingly slow and the IAF has only two squadrons of the Mark 1 type. The IAF ordered 83 Tejas Mk 1A (73 fighters plus 10 trainers) in 2021. HAL was required to deliver the first aircraft to the IAF by 31 March 2024 (22). However, it barely managed to ensure the first flight of this aircraft on 28 March 2024, indicating delivery delays. Even if HAL manages to produce 16 aircraft per year from FY 2024-25, it can only complete these deliveries by the end of FY 2028-29. The IAF intends to replace its fleet of Jaguar, Mirage-2000 and Mig-29 fighters with the Tejas Mk 2. HAL has commenced preliminary work on the Tejas Mk 2 and aims to launch its first flight in 2026 and deliveries to the IAF commencing by end-2029 (23). This seems highly optimistic and realistically, it may take a decade to develop and produce it. India's hunt for a fifth-generation fighter is centred on the Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft (AMCA) project. The Cabinet Committee on Security (CCS) accorded its ‘go-ahead’ for this project only in March. If all goes smoothly, AMCA will enter service around 2035-36.Even if all inductions were to occur as scheduled, the IAF chief has unequivocally stated that the IAF will have only 35 to 36 fighter squadrons (approximately 630 to 640 aircraft) by 2035 (24). This is also the year when the Chinese 6th generation fighter would enter service and the PLAAF would have 1000 J-20 5th generation aircraft (25)!

Risk Mitigation and Overcoming Shortages

From the foregoing part, the air power picture is becoming more disadvantageous for India. In the last five decades, Indian air power demonstrated by the IAF has been the primary deterrent against China. This was evident during the Ladakh stand-off and has remained so (26). The Chinese respect power and India’s air power generated awe and respect for India from a numerically larger adversary. Even though the IAF retains the edge in training and tactics, the PLAAF is trying to catch up fast. India’s continental obsession, inability to appreciate the strategic nature of air power in furthering national interests, a land-centric doctrine dominated by the largest service, and over-reliance on diplomacy to ‘manage’ China have eroded our deterrence and emboldened China. This puts our aspirations of becoming a significant power at immense risk and makes it easy for China to dominate Asia. Retaining our air power deterrence and overcoming shortages requires a creative approach. Generating credible capability in air power is not cheap and is time-consuming. A former IAF officer has calculated that the IAF would require approximately US $ 100 billion to reach a 42-squadron force by 2035 @ US $ 9 billion for two squadrons (27). Extrapolating it to a practical figure of 35 squadrons will cost US $ 63 billion to induct 14 new squadrons (including ten that would need replacement). In this regard, it is instructive to examine the path taken by some other nations.

To overcome gaps in development funding, synergise technical efforts and accelerate R&D, the U.K. and Italy have partnered with Japan in the Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP) to co-develop a sixth-generation stealth fighter aircraft (28). The initiative envisages amalgamating futuristic technologies involving over 1,000 manufacturers from these countries and integrating leading technologists, processes, and domain technology from each. The aircraft is slated to enter operational service by 2035. France, Germany, and Spain are collaborating on the Future Combat Air System (FCAS), which is on similar lines. The FCAS is expected to take to the skies in 2028 and enter service by 2040 (29). The nations in the GCAP and FCAS have unanimously emphasised the importance of these programmes in retaining their strategic autonomy, improving deterrence and ensuring regional stability.

India should leverage its good relations with nations that constitute the GCAP and FCAS and join either of the two programmes. This could be a game-changer for multiple reasons. First, it would catapult our technological capability. Secondly, as a stakeholder, the Indian industry would gain immensely through technology absorption, job creation and joining supply chains. Sharing costs makes sound economic sense, especially in a developing India. Beyond these, there are two more strategic benefits. One is that it would convey a credible strategic message to China that we are serious about countering its ‘powerplay.’ The other benefit would add to our credibility and capability of being a ‘preferred security partner’ in the Indo-Pacific. India will be seen as a nation that speaks softly but is unhesitant to wield the stick against a revisionist, belligerent and irrational China. While the solutions mentioned above, if implemented, will fructify only beyond 2035, the interim period remains critical. Hence, India must procure at least 100 additional Rafale (F4.2 standard) on a ‘fast-track’ basis for the IAF. Simultaneously, the growing Chinese presence in the Indian Ocean region (IOR) makes it imperative for the Indian Navy to have 60 Rafale-M. Our air power at sea requires a boost, and large aircraft carriers are the most potent repository of air power in the oceans. The government should urgently approve the construction of a larger aircraft carrier in the 65000 to 75000 tons category, capable of embarking more fighters and fixed-wing AEW aircraft. India should explore collaborating with France in the construction of this aircraft carrier. A combination of good economic growth and reducing wasteful and unnecessary public expenditure will greatly assist in funding such acquisitions.

Conclusion

It may be argued that the recommendation to import aircraft contradicts our quest for self-reliance. Self-reliance is indeed a noble endeavour and must be supported. However, stricter accountability must be enforced on DRDO and the DPSUs. A level playing field must be created for the private sector.Competitiveness requires encouragement, and the policy of nominating DPSUs for a project should be discontinued. Moreover, history has repeatedly proven that wars start when deterrence fails. Creating deterrence through capability development is a continuous process. Sacrificing deterrence while waiting endlessly to be self-reliant is the surest and fastest way to compromise national interests. It must be realised that enforcing peace with China can only be done from a position of strength. If deterrence fails, the ability to inflict decisive punitive punishment on China is centred on India’s air power. Whether terrestrially or over maritime spaces, Indian air power can cause China to lose face in a conflict. India needs to give this aspect adequate attention and sow this belief in the Chinese mind that it is best not to provoke the IAF into ‘firing in anger (30).’

A robust, reliable and resilient air power ‘eco-system’ demands adequate funding, a good technology base, private sector involvement, innovativeness, fruitful international collaborations and mastering niche technologies. The IAF has internalised air power education and lessons from various air campaigns. However, it has not ‘externalised’ these amongst the strategic community (including large segments of the other services), academia and the public. Resultantly, awareness and education about air power is abysmally low. This glaring lacuna in our national security discourse must be remedied. Air power should be introduced as an elective in undergraduate and post-graduate courses. An adequate pool of qualified, competent air power practitioners empowered with credible qualifications exists in the air veteran community. Colleges and universities can tap into this valuable human resource.

The multi-domain threat from China is a reality and cannot be tackled only by diplomacy and recourse to ‘civilisational ties.’ As witnessed in the Ladakh stand-off and incidents along the Indo-Tiber border in Arunachal Pradesh, China increasingly employs ‘grey-zone’ warfare against India on land. As the capabilities of PLAAF and PLAN grow, they will not hesitate to use such tactics against India in the air and maritime domain. China’s emphasis on air power intends to ensure a decisive victory at the least cost. Till now, Indian air power has steadfastly resisted them. However, the relative air power balance is perilously eroding. India has no option but to arrest it and reverse it. Otherwise, Viksit Bharat 2047 and ensuring national security will both remain pipedreams.

Endnotes

1. Doctrine of the Indian Air Force, IAP 2000-22, p 11

2. Rachel S. Cohen, ‘The Fighter Jet Era Has Passed’ available at https://www.airandspaceforces.com/article/the-fighter-jet-era-has-passed/ accessed on 12 June 2024

3. Air Marshal Ramesh Rai, ‘IAF: Structuring the Right Mix of Platforms and Technology’, South Asia Defence and Strategic Review, Vol 13 Issue 4, Sep/Oct 2019, pp 16-25

4. Anchit Gupta, ‘IAF’s Combat Fleet: The 80-Year Journey to 42 Squadrons’, 09 July 2023, available at https://iafhistory.in/2023/07/09/iafs-combat-fleet-the-80-year-journey-to-42-squadrons/ accessed on 12 June 2024

5. Vijay Mohan, ‘IAF approaches Russia to examine feasibility of life extension for IL-76 heavy-lift aircraft’, The Tribune, Chandigarh, 14 March 2024

6. Report of the CAG for the year ending March 2016, Union Govt. Defence Services (Air Force) Report No. 24 of 2017, p 36

7. Figures based on Ministry of National Defence, Taiwan, available at https://www.nids.mod.go.jp/english/publication/security/pdf/2024/08.pdf accessed on 14 June 2024. Also, see https://chinapower.csis.org/analysis/2022-adiz-violations-china-dials-up-pressure-on-taiwan/ accessed on 15 June 2024

8. https://www.flightglobal.com/defence/fighters-asw-aircraft-dominate-chinas-2023-aerial-incursions-against-taiwan/156344.article accessed on 15 June 2024

9. ‘South China Sea Dispute: Malaysia Accuses China of Breaching Airspace,’ BBC News, 01 June, 2021available at https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-57328868, accessed on 14 June 2024

10. U.S DoD. ‘Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2023’ available at https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/24041720/2023-military-and-security-developments-involving-the-peoples-republic-of-china.pdf accessed on 13 June 2024

11. Ibid

12. Govt. of Australia, ‘Statement on unsafe and unprofessional interaction with PLA-Air Force’ 06 May 2024, available at https://www.defence.gov.au/news-events/releases/2024-05-06/statement-unsafe-and-unprofessional-interaction-pla-air-force accessed on 13 June 2024

13. Sakshi Tiwari, ‘Taiwan Reports 241 Incidents Of Chinese Incursions In June; Comes After Ex-Navy Captain ‘Tests’ Its Defenses’, The Eurasian Times, 13 June 2024 available at https://www.eurasiantimes.com/taiwan-reports-241-incident-of-chinese-incursions/ accessed on 13 June 2024

14. U.S DoD. ‘Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2023’

15. Ibid

16. https://www.iiss.org/en/online-analysis/military-balance/2023/02/chinas-air-force-modernisation-gaining-pace/ accessed on 14 June 2024

17. Rick Joe, The Diplomat, 11 June 2024 available at https://thediplomat.com/2024/06/chinas-6th-generation-and-upcoming-combat-aircraft-2024-update/ accessed on 13 June 2024

18. Ibid

19. Group Captain Praveer Purohit (retd), ‘Overcoming Shortages’, Millennium Post, New Delhi, 17 May 2024. Also, see https://www.eurasiantimes.com/armed-with-1200-warplanes-indian-air-force-in-a-tight-spot-against-chinese-plaaf-over-the-himalayas/ and https://www.sps-aviation.com/story/?id=2988&h=PLAAFs-Growing-Threat-%E2%80%93-Challenge-for-the-IAF

20. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com//news/defence/hindustan-aeronautics-aims-to-raise-annual-light-combat-aircraft-production-threefold-in-3-years/articleshow/105537535 accessed on 14 June 2024

21. https://www.iiss.org/en/online-analysis/military-balance/2023/02/chinas-air-force-modernisation-gaining-pace/ accessed on 14 June 2024

22. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/indian-air-force-likely-to-get-its-first-tejas-mk-1a-aircraft-in-july-101715873144459.html accessed on 14 June 2024

23. Raunuk Kunde, ‘Tejas Mk 2 deliveries to IAF expected by 2029, HAL Chief Confirms’, 23 April 2024, available at https://idrw.org/tejas-mk2-deliveries-to-iaf-expected-by-2029-hal-chief-confirms/ accessed on 06 May 2024

24. Snehesh Alex Philip, ‘Mirages, MiG 29s, Jaguars to be phased out by 2035, IAF seeks more aircraft’, The Print 04 October 2022 available at https://theprint.in/defence/indias-fighter-squadron-strength-falls-to-29-iaf-seeks-more-aircraft/1154121/ accessed on 05 May 2024

25. Ritu Sharma, ‘China Aims At 1000 J-20 Fighters By 2035 When India Gets 5th-Gen AMCA; Can IAF Narrow The Gap With PLAAF’, The Eurasian Times, 11 June 2024 available at https://www.eurasiantimes.com/china-aims-at-1000-j-20-fighters-by-2035/ accessed on 14 June 2024

26. Praveer Purohit, ‘Three years of stand-off: Air power remains the key deterrent against China’, Financial Express, 10 May 2023, available at https://www.financialexpress.com/business/defence-three-years-of-stand-off-air-power-remains-the-key-deterrent-against-china-3081757/ accessed on 10 May 2023

27. Air Marshal Anil Chopra (retd), ‘IAF Modernization – Challenges Ahead’, South Asia Defence and Strategic Review, Vol 13 Issue 3 Jul/Aug 2019, pp 34-39

28. Takeshi Sakade, ‘The GCAP will see Japan’s fighter jet ambitions soar’, East Asia Forum, 20 May 2023, available at https://eastasiaforum.org/2023/05/20/the-gcap-will-see-japans-fighter-jet-ambitions-soar/ accessed on 20 April 2024

29. https://www.bundeswehr.de/en/the-fcas-nations-are-consolidating-their-cooperation-5765642 accessed on 14 June 2024

30. ‘Firing in anger’ means to shoot for a purpose in war. It is a military term used to signify the kinetic use of a weapon.