Abstract

India-Malaysia relations date back several centuries. The wave of interactions between India and Southeast Asia remained unhinged till the advent of the European powers into Asian waters. The structural and political constraints inflicted by the cold war superpower rivalry on the international system left any scope for the growth of India-Malaysia relations. India's initiation of the "look east" policy in 1992 and emerging post-cold war dynamics facilitated the rapid growth in the relations between India and Malaysia and India-ASEAN in general. The recent divergence of perspectives on the emerging Indo-Pacific construct and political differences between these two maritime neighbours has left a gap in the discourse of India-Malaysia maritime relations. This paper explores the possibilities that the Indo-Pacific era, notably an era of re-emerging great power rivalry and strategic uncertainty, has to offer to complement the maritime relations between India and Malaysia, enhancing their partnership and role in sustaining the emerging regional architecture open and stable. The paper first provides an introduction to the study followed by the themes: 1) India-Malaysia Maritime Connections: A Historical view, 2) India-Malaysia Relations During the Cold War Period (1945-1992), 3) India's Look East Policy, 4) "Look East" and India-Malaysia Maritime Relations, and 5) India-Malaysia Dynamics In The Indo-Pacific.

Keywords: India-Malaysia, ASEAN, Maritime relations, the Indo-Pacific

Introduction

India and Malaysia have trade and cultural links dating back over two millennia. India's cultural influence had been predominant in the South East Asian region, including Malaysia, between the 9th Century to 13th Century AD through the imperial advent of the Chola empire of South India. Both the nations are Indian Ocean littorals and became independent from colonial rule post World War 2, India in 1947, and Malaysia in 1957. India and Malaysia established diplomatic relations in 1957, and the two nations commemorate the 65th anniversary of their diplomatic relationship in 2022. Malaysia had only seven international links when it gained independence in 1957, with India being one of them. Malaysia had strong political affinities with India during the early relations between the two countries. Malaysia fiercely condemned China's conquest of Tibet in 1959 and established a "Save Democracy Fund" when the Sino-Indian war broke out, as it believed that China's unwarranted action against India stirred the crisis.

In fact, during the 1965 Indo-Pak war, Malaysia supported India, and both countries supported their positions in the Commonwealth. There was a convergence of perspectives on specific international issues, including apartheid in South Africa, decolonization, the non-aligned movement (NAM) formation, reform of the global economic order, and South empowerment. Malaysia's usually pro-Western posture, particularly during the Vietnam War (1954–1975) and the Cambodian conflict (1978–1991), prevented any deeper cooperation with India, which took a more pro-Soviet and pro-Hanoi stance during those trying years (K.S. Nathan, 2013). India's Look East Policy (LEP) has unfolded many opportunities to build stronger economic and political ties with East Asian nations leading to the second phase of the LEP that enhanced "security cooperation, including joint operations to protect sea lanes and pooling resources in the war against terrorism" (Dhanda & Kumar, 2012). India-Malaysia relations gained momentum in the last two decades, culminating in the nations signing the 'Enhanced Strategic Partnership' in 2015. Even though bilateral relations have generally been amicable, former Malaysian President Mahathir Mohamad criticized India's policies, such as revoking Article 370 of Jammu & Kashmir and the Citizenship Amendment Act, which stirred distraught between the two countries. However, there are sufficient historical precedents for a broader and deeper engagement of India and Malaysia, especially in maritime-related issues, given the 21st Century geopolitical and economic dynamics in the Eastern Indian Ocean Region (EIOR), the South China Sea, and the larger Indo-Pacific region.

India-Malaysia Maritime Connections: A Historical View

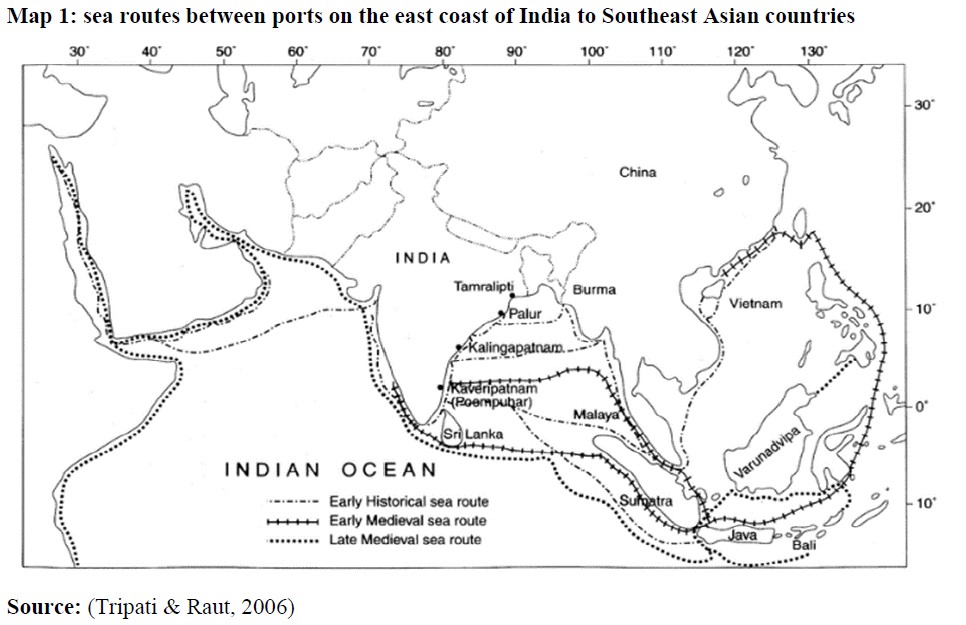

India and Malaysia have been interconnected for several millennia through high-seas trade and cultural interactions continuing to the present day. Many ancient Indian texts, including the Vedas and Mahabharata, refer to long-distance voyages between India and South East Asia (SEA), and Ramayana has specific reference to Yaradvipa (Java Island) and Suvarnadvipa (Sumatra and the Malay peninsula) (Sikri, 2013, as cited in, Krishnan, 2015). Since the reign of Raja Chola in the 11th Century CE, trade activities between India and Malaysia have been significant, leading to many Indian traders settling in the major Malaysian ports. Later the Gujarati communities emerged as prominent traders and travellers to SEA due to their vast knowledge of shipbuilding and seafaring. The ships heading East from India docked at the western coast of the Malaysian peninsula and places like Panang, Malacca, and Johor, while ships heading westward from SEA called in at the Indian ports such as Nagapatnam, Masulipatnam, Calicut, Cambay, and Goa. The Malays had strong open-sailing knowledge, and their familiarity with wind circulation helped them 'ride the monsoon winds' throughout the year. A Malay-speaking community Orang Laut (sea people), emerged as protectors of the sea from pirates in SEA by the end of the 15th Century, facilitating maritime interactions in the region, including India's trade activities (Krishnan, 2015, 47-48).

The Portuguese touched down on the East coast of India in the late 15th Century with the motivation of 'God, Glory, and Gold.' They were amazed by the region's abundance of spices and soon imagined trading in spices rather than gold. The successive advent of other European powers, the British, the French, and the Danish, challenged the domination of Indian merchants in the EIOR, disrupted the free-trading accord, and turned the region into a battlefield for competition to establish a political and economic monopoly. By the mid-16th Century, the Portuguese flew their flags at several ports across the Indian Ocean, such as Colombo (1505), Socotra (1507), Goa (1510), Malacca (1511), Hormuz (1515), and Diu (1535). The Portuguese foothold in Malacca, the Entrepot of the EIOR, and the imposition of taxation under the cartaz-armada-qalifa system, impacted 'the overall balance of power of trading networks at the EIOR' (Krishnan, 2015, 60). However, the maritime bonds between Malaya and India remained intact. By the 18th Century, the Portuguese lost their hold of Malacca to the Dutch. The Dutch took over the textile trade of Bengal, especially cotton and raw silk, and tried and failed to overshadow the influence of Indian merchants in the EIOR due to the latter's closer bonds with the Malay royalty, with some even obtaining administrative positions in the Malay Sultanate.

The British opened the Panang port in 1786 in rivalry with Malacca, marking its rise in the Malay world. Indian merchants preferred trading through Panang due to the free trade policy of the British, and soon Panang threatened the Entrepot title of Malacca. The Dutch succumbed to the British pressure and gave up Malacca diverting their attention to inner Malay. The British also established another entrepot Singapore in 1867. Though the trade volume between Malay and India reduced during British control, the maritime interactions between the two regions remained robust.

India-Malaysia Relations During the Cold War Period (1945-1990)

After World War 2, India and Malaysia, as newly independent countries, focused on nation-building and economic development and avoided Cold war politics. Both nations perceived threats from their land borders, and territorial integrity became an imperative of their policies. While India inherited Royal Indian Navy (RIN), which relied on British Royal Navy (BRN) till the mid-1960s and lacked an independent structure, Malaysia had only one army division without an Air force or any other force. However, India envisioned building blue-water naval capabilities to defend its vast coastlines and protect trade routes, but the economic constraints and the necessity of vesting more on land forces scaled down the country's maritime ambitions. Malaysia focused on territorial defence from communist insurgencies, for which it sought help from the British. India also looked to the British and Soviet Union for military assistance, as Pakistan's membership of SEATO and CENTO meant naval supremacy in the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal.

India avoided alliances and acted as a leading force behind the non-alignment movement (NAM) that advocated the eradication of colonialism, imperialism, and neo-colonialism and emphasized territorial integrity, sovereignty, and independent foreign policy. Unlike India, Malaysia viewed the western ideology as deterrence against communism. It signed a bilateral defence agreement with the United Kingdom, the Anglo-Malaysian Defence Agreement (AMDA), in 1957, which was later replaced by the Five Power Defence Agreement (FPDA) in 1971, consisting of five commonwealth countries, the UK, Malaysia, Singapore, Australia, and New Zealand. Being a newly independent nation, Malaysia held the sentiment of neutrality, anti-colonialism, territorial integrity, and sovereignty and attended the 1970 Lusaka summit announcing its adoption of the NAM approach in shaping its foreign policy. Though the summit brought India and Malaysia closer, the latter's signing of FPDA became an irritant in their bilateral relations. India and Malaysia also played an essential role in establishing the Indian Ocean as a zone of peace through the NAM and the UN to ensure the region is free from nuclear proliferation, weapons of mass destruction (WMDs), and great power military build-up. NAM adopted the declaration of the Indian Ocean as a zone of peace in the 1973 Algiers summit and welcomed the setting up of an ad-hoc committee by the UN to consider the measures aimed at implementing the declaration (Fourth Summit Conference of Heads of State, Non-Aligned Movement, 1973). The member countries stressed implementing the Zone of Peace, Freedom, and Neutrality (ZOPFAN) in the IOR in the subsequent NAM summits and UNGA meetings, and Malaysia expressed its intention to expand ZOPFAN into Southeast Asia (SEA).

India's "Look East" Policy: A progressive Step in Indian Foreign Policy Towards its East

The disintegration of the USSR and the end of the Cold War allowed the countries worldwide to manoeuvre in the new world order freely without the preponderance of cold war fractions. India's relations with the SEA countries remained negligible throughout the Cold War due to its preoccupation with the security threats in its region. The state-controlled economic model did not allow India to forge economic ties with the East Asian countries already experiencing rapid economic growth. The collapse of India's major economic and defence partner, the Soviet Union, the severe internal financial crisis that followed, and the logic of globalization compelled India to embark on economic reforms, leaving it past its inward-looking economic orientation. In 1992, Indian Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao launched the "Look East" policy underscoring the significance of the SEA for India in the changing international environment. The Look East policy initially placed economic engagement as the central tenet in India-SEA relations. However, the SEA regional countries did not take India's Eastward orientation seriously until the turn of the 21st Century (Sikri, 2009).

In 1992, India joined as a "sectoral dialogue" partner of ASEAN on trade, investment, tourism, science, and technology. The ASEAN members elevated India's position from a "sectoral dialogue" partner to a "full dialogue" partner in 1996, "allowing for cooperation on political and security issues" (Osius & Raja Mohan, 2013). India subsequently participated in ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) in 1996. India's integration with SEA has steadily evolved ever since. India played a prominent cooperative role in establishing the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-sectoral Scientific Technological and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) in 1997, along with several South and Southeast Asian nations.

India's "dialogue partner" status was upgraded to a summit-level partner in 2002 at the first India-ASEAN summit, in which leaders of both parties affirmed their resolve to advance cooperation "to promote peace, stability, and development in the Asia-Pacific region and the world" (Ministry of External Affairs, 2002). The 2nd India-ASEAN summit held in 2003 resulted in the leaders signing three important accords: 1) the ASEAN-India Framework Agreement on Comprehensive Economic Cooperation that laid the basis for establishing an ASEAN-India Free Trade Area (FTA), 2) an agreement on India's accession to Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia (TAC) to ensure peace, stability, and development in SEA 3) a joint Declaration for Cooperation in Combatting International Terrorism. At the 3rd India-ASEAN summit 2004, the members signed the ASEAN-India Partnership for Peace, Progress, and Shared Prosperity, through which members expressed their commitment to cooperate in several domains, including sustainable growth, poverty alleviation, strengthening the UN system, cooperating in other multilateral fora, addressing the common security challenges including food, human and energy security, combatting international terrorism and other transnational crimes such as drug trafficking, human trafficking, cybercrimes and economic crimes, regional infrastructure development, cooperation in science and technology and human resource development, and promoting people-to-people ties (Association of Southeast Asian Nations, 2004).

ASEAN established the East Asian Summit (EAS) in 2005, with India as a founding member. According to Rajiv Sikri, India's membership in the EAS signifies the "success and credibility of India's "Look East" policy that bridged the gaps between India and SEA in a psychological, political, and strategic sense" (Sikri, 2009). The fifth India-ASEAN summit, 2007, focused on an India-ASEAN free trade agreement (FTA), and the members signed FTA in trade in 2009, which came to effect in 2010. New Delhi hosted the India-ASEAN 20-year commemorative summit in 2012, in which the India-ASEAN members elevated their dialogue partnership to a strategic partnership (Overview of India-ASEAN Relations, 2022). At the 25-year commemorative summit 2018, India and ASEAN agreed to utilize their strategic partnership to build cooperation in the maritime domain. 2022 has been designated as the India-ASEAN friendship year, marking 30 years of their relations (Overview of India-ASEAN Relations, 2022). The economic ties between India and ASEAN have advanced significantly since the "Look East" policy was implemented, with total trade rising from 5.836 billion USD in 1996 to 98.39 billion USD in 2021 (Ministry of Commerce and Industry, GOI, 2022). The "Look East" policy led to the evolution of India-ASEAN relations into a multi-dimensional scope, enhancing political and security ties.

Maritime security cooperation between India and ASEAN is the most significant area that has drawn attention from the beginning of the 21st Century. India geared up maritime security cooperation in the Indian Ocean region through multilateral naval exercises such as Milan, launched in 1995, with four countries participating in the first edition. The number of participants grew to 40 in the 11th edition of the exercise conducted in 2022 (Naval Exercise MILAN Concludes in Visakhapatnam, 2022). India also initiated the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS) in 2008 to provide a forum for the countries to discuss regional naval cooperation and confidence building among the Indian Ocean littorals. In 2012, India and ASEAN declared their commitment to "strengthening cooperation to ensure maritime security, freedom of navigation, and safety of sea lanes of communication for unfettered trade movement in accordance with international law, including UNCLOS…, through engagement in the ASEAN Maritime Forum (AMF) and its expanded format, to address common challenges on maritime issues, including sea piracy, search and rescue at sea, maritime environment, maritime security, maritime connectivity, freedom of navigation, fisheries, and other areas of cooperation" (Vision Statement: ASEAN-India Commemorative Summit, 2012). Besides engaging through multilateral fora, India signed bilateral security cooperation agreements with Southeast Asian countries, including Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.

"Look East" and India-Malaysia Maritime Relations

India's "Look East" policy paved the way for the growth of India-Malaysia relations. The trade and economic relations between the two countries increased significantly after implementing the Malaysia-India Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement (MI-CECA) in 2011. The bilateral trade increased 17 times from US $ 0.6 billion in 1992 to US $ 10.3 billion in 2010, and by the end of 2021, the figures reached US $ 16.66 billion (Ministry of Commerce and Industry, 2022). India has emerged as one of the ten largest trading partners for Malaysia, while Malaysia is the 13th largest trading partner for India and the third largest in the ASEAN group (High Commission of India, Kuala Lumpur, 2022).

India-Malaysia defence relations have also grown steadily over the years. India and Malaysia signed an MoU on Defence Cooperation in 1993, considered the cornerstone of defence relations between the countries. This MoU resulted in the setting up of the Indian Air Force (IAF) ground training on MiG-29 aircraft with about 100 personnel of the Royal Malaysian Air Force (RMAF) in 1994 (Chandran, 2014). India-Malaysia navy-to-navy interactions have grown through the biennial LIMA exhibition and MILAN exercises. In 2017 the Royal Malaysian Navy and the Indian Navy conducted the first-ever field training exercise (FTX), Exercise Samudra Laksmana, in the Malacca Strait. There is no doubt that India-Malaysia defence relations have seen an improvement, but the interactions are restricted to the area of training, including courses and seminars, limiting the maturity of the relations (Chandran, 2014). There are great possibilities driven by sufficient precedents and a rationale for a broader and deeper engagement of India and Malaysia, especially in maritime security cooperation, given the 21st Century geopolitical and economic dynamics in the Eastern Indian Ocean Region (EIOR), the South China Sea, and the larger Indo-Pacific region.

India and Malaysia are Indian Ocean littorals and maritime neighbors located at the most strategic point, i.e., the Eastern Indian Ocean that links the Indian and the Pacific Ocean through an entrepot like the Malacca strait and other sea lines. Around 40% of the world's trade transits through the Malacca Strait, making it the most crucial strategic choke point. Both countries are highly dependent on the seas for trade and connectivity and are open to maritime threats from their eastern and western sides. As maritime neighbors, India and Malaysia share similar interests in cooperating to maintain the safety and security of the EIOR, the Malacca strait, and the region where the two seas are confluent.

India-Malaysia Dynamics in the Indo-Pacific

The changing geopolitical scenario in the Indian Ocean and the Western Pacific is a common concern for both nations. India is an ardent supporter of ASEAN centrality and its leadership in shaping the future of the East Asian order. The country is aware of the changing balance of power in favor of China, its de-unifying impact on the ASEAN in addressing issues like maritime territorial conflicts in the South China Sea, and its debilitating effects on the rules-based order in the region.

The economic integration of Asia with itself, the rise of China and its dependence on fossil fuels from West Asia and energy and mineral resources from Africa, and the growing trade and connectivity of India with East Asia have blurred the boundaries between the Indian Ocean and the Pacific Ocean (Osius & Raja Mohan, 2013). The foray of China and India into each other's realms, the western Pacific and the Indian Ocean, respectively, and the intersection of maritime interests of these major powers, including the US, have conjured up a new geographical imagining, the "Indo-Pacific," with a distinctive geopolitical character associated with it. It is in India's interest to collaborate with ASEAN and its members individually to preserve ASEAN centrality in the SEA region. China's naval presence across the Indian Ocean, especially at the crucial choke points, is a concern for India and affects India's power projection in the Indian Ocean. While Malaysia maintains positive relations with China, it is wary of China's dominance and territorial claims in the SCS and its threat to a rules-based order in the region. Hence, maritime cooperation through bilateral naval exercises, training for rescue operations, and disaster management in the EIOR and the South China Sea would be a win-win for India-Malaysia relations.

India intends to advance its cooperation with ASEAN countries by implementing its "Act East" adopted in 2015. India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi, in the 2018 Shangri la dialogue, presented India's vision of the Indo-Pacific and expressed his nation's endeavor for a free, open, and inclusive Indo-Pacific. He stated that the ASEAN is central in the Indo-Pacific, and India seeks to cooperate with ASEAN members for an architecture for peace and security in the region (Ministry of External Affairs, 2018). With ASEAN Centrality as its foundation, India's Act East Policy and Indo-Pacific strategy complement one another. India is attempting to harmonise its Act East Policy with the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific (AOIP) through initiatives such as the Security and Growth for Everyone in the Region (SAGAR) and Indo-Pacific Oceans' Initiative (IPOI) initiatives (MP-IDSA, 2022).

India's PM launched the Indo-Pacific Oceans Initiative (IPOI) during the East Asia Summit on 4 November 2019 in Thailand. The IPOI is a framework for regional cooperation in the Indo-Pacific region, focusing on maritime security, connectivity, and sustainable development. The IPOI aims to bridge the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and its dialogue partners in the Indo-Pacific region and to promote greater coordination among existing institutional structures. ASEAN's centrality and outlook on the Indo-Pacific complement the IPOI, which seeks to promote an inclusive, rules-based order in the region. The IPOI focuses on seven priority areas; (1) Maritime Security; (2) Maritime Ecology; (3) Maritime Resources; (4) Capacity Building and Resource Sharing; (5) Disaster Risk Reduction and Management; (6) Science, Technology and Academic Cooperation; and (7) Trade Connectivity and Maritime Transport (Chauhan et al., 2020). The initiative is not driven by any balance of power considerations in the region and it is open to all the interested parties (Mishra, 2023). Hence, IPOI is seen as a way to promote greater regional cooperation and stability in the Indo-Pacific.

India is also a member of the US-led Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) initiated on 23 May 2022. IPEF has 12 member countries, and it bases on four pillars: fostering high-standard, inclusive, free, and fair trade; building transparent and resilient supply chains; creating resiliency to climate change through the use of technology and clean energy; strengthening tax, anti-money laundering, and anti-bribery regimes to reduce tax evasion and corruption in the region. India was initially reluctant to join the IPEF as it preferred dealing in bilateral trade deals with the US and addressing larger Indo-Pacific issues through the quad mechanism. The flexibility and inclusiveness of the IPEF and its focus on supply chains are the areas that attracted India to this framework. India's Ministry of Commerce & Industry described the IPEF summit as "a meeting to bring together a group of like-minded, rules-based, transparent countries with a shared interest in an open Indo-Pacific region" (Ministry of Commerce & Industry, 2022).

Though Malaysia is strategically located in Southeast Asia at the gateway of the Indo-Pacific region, connecting the Indian Ocean to the Pacific Ocean, it remained silent or rather neutral in adapting the new geospatial nomenclature. ASEAN acknowledged the relevance of the Indo-Pacific construct in ASEAN's Outlook on the Indo-Pacific. The underlying factor that keeps Malaysia absent in the Indo-Pacific discourse is that it views the new geopolitical concept as an external construct, and taking an open and rigid position will increase the chance of entrapping the country in the great power conflict (Kuik, 2020).

Rastam Mohd Isa, the former chairman of the Institute of Strategic and International Studies (ISIS), one of Malaysia's leading think tanks, acknowledged at the 33rd Asia Pacific Roundtable (APR) in 2019 that, while the discussion on the Indo-Pacific is growing, ISIS Malaysia has no plans to rename its signature international conference to the "Indo-Pacific Roundtable." Nonetheless, a panel discussion titled "Asia Pacific vs. Indo-Pacific: Rationale, Contestation, and Implications" was included to kick off a conversation about what the Indo-Pacific concept means for the region's security (Hooi, 2022).

Malaysia expressed its concerns about the recent developments in the Indo-Pacific. For instance, Malaysia is alarmed over the AUKUS (Australia-UK-US) security partnership signed in September 2021. The partnership aims to enhance cooperation in the areas of defense and technology, including the development of nuclear-powered submarines. Malaysia and other ASEAN countries have called for the partnership to be transparent and inclusive, considering the interests of all the regional countries. In a statement, the Malaysian Ministry of Foreign Affairs expressed its hope that the partnership would not lead to an arms race or destabilize the region's security architecture and emphasized the importance of upholding the principles of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and ensuring freedom of navigation in the region (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2021). Malaysia's defense minister, Datuk Seri Ismail Sabri Yaakob, has said that the AUKUS partnership should not affect the existing security arrangements in the region, "Our endgame as always is to ensure the region's stability, regardless of the balance of powers (between) the US or China" (Strangio, 2021).

Nevertheless, Malaysia joined the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF). Mohamed Azmin Ali, Minister of International Trade and Industry, during the virtual IPEF Ministerial Meeting in July 2022, proposed for the IPEF partners to collaborate to set up a centre of excellence to provide a cohesive and structured platform to facilitate seamless and dynamic exchanges of ideas and recommendations (MIDA, 2022). Prime Minister Datuk Seri Ismail Sabri Yaakob speaking at the 27th International Conference on the Future of Asia in Tokyo, stated that Malaysia is confident that the IPEF will strengthen economic cooperation between countries in the Indo-Pacific and the ASEAN region. The PM expressed that Malaysia is ready to discuss relevant issues through the IPEF to ensure the members can optimise the economic and strategic benefits outlined in the framework (Hooi, 2022).

Malaysia's presence in the Indo-Pacific mechanisms signifies that the country is interested in engaging and building a non-political framework and endeavours to address larger regional issues such as trade, infrastructure growth, connectivity, economic security, cyber security, and maritime security. As a potential middle power and a founder member of ASEAN, Malaysia aims to ensure regional stability and cooperation in its immediate region and intends to be a reliable partner in addressing issues of international importance (Noor, 2023). Malaysia has opportunities to play a significant role in the framing of regional architecture by collaborating with regional middle powers, including India and Japan, in what Stephen R. Nagy calls "neo-middle power diplomacy," which includes maritime security, digital economy, and economic cooperation to ensure that the middle power interests are not overridden by the Sino-US rivalry (Nagy, 2022).

Conclusion

India-Malaysia relations have witnessed great heights since the end of the cold war as India initiated its "look east" policy and penetrated the Southeast Asian regional dynamics economically and politically. The return of great power politics in the region by the turn of second decade of the 21st Century, India's reaction to the changing regional environment, its adoption of the new Indo-pacific regional framework, and Malaysia's reluctance to the Indo-Pacific left a void in the discourse of India-Malaysia relations. Malaysia's participation in the IPOI and IPEF shows that the country is not entirely ignoring the Indo-Pacific framework. Instead, it seeks a regional framework that is not exclusive of any regional country, especially China, and one that moves beyond the balancing politics focusing on the other larger regional issues, including trade, connectivity, supply chains, maritime security (maritime piracy, terrorism, cyber-attacks) sustainable growth, and technology sharing. As an active member in the Indo-Pacific mechanisms, India can engage Malaysia more in platforms such as the IPOI and IPEF and other multilateral platforms such as ASEAN to maintain the regional architecture free, open, and inclusive underpinning ASEAN centrality as it envisions. Besides being a realm of maritime uncertainty, the Indo-Pacific offers a lot of possibilities for India-Malaysia in enhancing their maritime relations, which would be of great significance in maintaining the regional order stable and open.

References

Association of Southeast Asian Nations. (2004). ASEAN-India Partnership for Peace, Progress and Shared Prosperity. Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

Chauhan, P., De, P., Parmar, S. S., & Kumarasamy, D. (2020). Indo-Pacific Cooperation: AOIP and IPOI (No. 3).

Dhanda, S., & Kumar, P. (2012). INDIA AND SOUTHEAST ASIA: AN ANALYSIS OF INDIA'S LOOK EAST POLICY. Journal of Global Research & Analysis, 1(2), 18–34.

Fourth Summit Conference of Heads of State or Government of the Non-Aligned Movement, (1973).

High Commission of India, Kuala Lumpur. (2022). High Commission of India, Kuala Lumpur.

Hooi, K. Y. (2022, August 9). Malaysia and the 'Indo-Pacific': Why the Hesitancy? The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2022/08/malaysia-and-the-indo-pacific-why-the-hesitancy/

Krishnan, T. (2015). Emerging Security Paradigm in the Eastern Indian Ocean Region: A Blue Ocean of Malaysia-India Maritime Security Cooperation. King's College.

K.S. Nathan. (2013). INDIA-MALAYSIA DEFENCE RELATIONS. In Ajaya Kumar Das (Ed.), INDIA-ASEAN DEFENCE RELATIONS (pp. 218–235). RSIS.

Kuik, C. C. (2020). Mapping Malaysia in the Evolving Indo-Pacific Construct.

MIDA. (2022, July 27). Malaysia proposes establishment of Indo-Pacific Economic Framework Centre of Excellence. Malaysian Investment Development Authority. https://www.mida.gov.my/mida-news/malaysia-proposes-establishment-of-indo-pacific-economic-framework-centre-of-excellence/

Ministry of Commerce & Industry. (2022, September 10). The Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity. Ministry of Commerce & Industry. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1858243

Ministry of Commerce and Industry. (2022). Foreign Trade (ASEAN). Ministry of Commerce and Industry.

Ministry of External Affairs. (2002). Joint Statement of the First ASEAN-India Summit. Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India.

Ministry of External Affairs. (2018). PM's Keynote Address at Shangri La Dialogue . Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India.

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, M. (2021). ANNOUNCEMENT BY AUSTRALIA, UNITED KINGDOM AND THE UNITED STATES ON ENHANCED TRILATERAL SECURITY PARTNERSHIP – AUKUS . https://www.kln.gov.my/web/guest/-/announcement-by-australia-united-kingdom-and-the-united-states-on-enhanced-trilateral-security-partnership-aukus

Mishra, R. (2023, February 10). Re-imagining Indo-Pacific construct. Institute of Strategic & International Studies. https://www.isis.org.my/2023/02/10/re-imagining-indo-pacific-construct/

MP-IDSA. (2022, April 20). Why does India focus on ASEAN Centrality in its Indo-Pacific strategy? What are the challenges involved in it? MP-IDSA. https://www.idsa.in/askanexpert/india-focus-on-asean-centrality-in-its-indo-pacific-strategy

Nagy, S. R. (2022). Middle-Power Alignment in the Free and Open Indo-Pacific: Securing Agency through Neo-Middle-Power Diplomacy. Asia Policy, 17(3), 161–179.

Naval Exercise MILAN Concludes in Visakhapatnam . (2022). The Hindu.

Noor, F. A. (n.d.). Projecting Malaysia as a Middle Power: How Defence Diplomacy Complements Our Foreign Policy Agenda. Malaysian Institute of Defence Security. Retrieved March 23, 2023, from https://midas.mod.gov.my/gallery/publication/midas-commentaries/77-projecting-malaysia-as-a-middle-power-how-defence-diplomacy-complements-our-foreign-policy-agenda

Osius, T., & Raja Mohan, C. (2013). Enhancing India-ASEAN Connectivity.

Overview of India-ASEAN Relations. (2022). Ministry of External Affairs.

Sikri, R. (2009). India's "Look East" Policy. Asia-Pacific Review, 16(1), 131–145.

Sikri, V. (2013). India and Malaysia: Intertwined Strands. ISEAS.

Strangio, S. (2021, October 13). Malaysian Defense Minister Hoping for ASEAN Consensus on AUKUS. The Diplomat. https://thediplomat.com/2021/10/malaysian-defense-minister-hoping-for-asean-consensus-on-aukus/

Suseela Devi Chandran. (2014). Malaysia and India's Look East Policy (LEP): Hand in Hand Towards Greater Cooperation. Journal Of Administrative Science, 11(1).

Tripati, S., & Raut, L. N. (2006). Monsoon wind and maritime trade: A case study of historical evidence from Orissa, India. Current Science , 864–871.

Vision Statement: ASEAN-India Commemorative Summit. (2012, December). Ministry of External Affairs.