Introduction

The post-Soviet world order has leaned towards multipolarity after being unipolar in favour of the United States during the initial years. This changed nature of geopolitical dynamics allowed various states to carve a niche for themselves at the global level. While Russia and Israel along with the United States maintained their supremacy over arms and ammunition, South Asian countries like Vietnam, Taiwan, Singapore, South Korea, and Japan made a significant impact on the electronics manufacturing industry. Despite this, none of these countries could challenge the ‘superpower’ status of the United States which held the potent weapon of being a global leader in defence, technology, and trade alike.

However, China significantly challenged the undisputed status of the United States on all three of these fronts. It is to be noted that this tussle between China and the United States, while premised upon a strong economic and geopolitical strife, also has an ideological overtone to it that resembles the re-emergence of the nature of Cold War politics. However, unlike the Soviet Union, China has invested heavily in contrasting its Communist regime by bolstering economic development within and beyond its territory. China has also focused on making significant territorial gains in its neighbourhood, especially those complementing its commercial and financial strategies. China’s focus on annexing Taiwan and Hong Kong by the end of this decade points toward its seriousness in fulfilling those objectives. (Amonson & Egli, 2023, 40)

Neutralising India’s rise in the three sectors mentioned above is essential for the fulfilment of China’s ambitious objectives, which rely upon its ability to impose itself as the sole superpower among the South, Southeast Asian, and Oceanic states, such as to have a command to authorise and control the use of maritime routes for trade and defence in this region. Because of this, China has taken strategic initiatives to weaken India’s claim in the area.

Indo-Sino relations under the current geopolitical dynamics are a combination of using development as a soft power and other states in the region to not only build cordial ties but also advance self-interests through development and trade. This fierce competition between the two Asian giants has transcended the realm of trade and commerce. Essentially, trade and commerce have become a mere subset of the geopolitical superstructures that both the states envision and counter. This paper evaluates an element of India’s prospects in the Indian Ocean region, focusing on China’s alleged String of Pearls strategy and emphasising the threat it puts to India’s trade and political interests.

Nature of Indo-Sino Conflict

India established diplomatic ties with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on April 1st, 1950, becoming the first non-communist/socialist state in Asia. The formation of the PRC was only after a conflict wherein the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) defeated the incumbent ruling party of the Republic of China. Despite this political instability, the Indian government led by Jawaharlal Nehru deemed it important to establish cordial ties with China to cater to its policy of non-alignment and peaceful neighbourhoods.

The same intentions were reflected in the Five Principles of Peaceful Co-existence (Panchsheel) which was agreed upon by both parties in the Agreement on Trade and Intercourse between the Tibet region of China and India signed on April 29, 1954. (External Publicity Division Ministry of External Affairs Government Of India, n.d.)

However, this promise of peace and cooperation was broken swiftly by China as the Indo-China war broke out in 1962. Chinese Chairman Mao Zedong engaged in virtue signalling during the 1970s, hinting at a rekindling of ties between the two countries. This approach did not actuate as the Indo-Pak war broke out during the 1970s, with the Soviet Union backing India. This came at a time when Beijing was in a border conflict with Moscow. This was a matter of discomfort for China, which was reflected in Mao deeming India as an appendage state. This marked a divergence in bilateral ties that would never mend ways. China subsequently began engaging with Pakistan diplomatically and in trade and defence sectors, advancing its geopolitical and economic interests.(Gokhale, 2022)

Moreover, it is to be noted that the Indo-Sino strife is restricted not only to bilateral disputes but also to contending interests globally, especially in the South and Southeast Asian region. It is alleged that China drags the border conflict with India to force the latter to devote its resources to the region, while the former has effectively used its military and financial prowess to play an influential role in the Indian subcontinent, South Asia and Oceania.

It is thus imperative to understand the role played by other states in this region and its impact on India’s policy towards China.

String of Pearls: India’s primary geopolitical threat

Historically, waterways connected the Western world with the East. The same waterways acted as a medium for the entry of colonial powers in the east and also acted as a tool for trade and related embargos in the evolving nature of geopolitics. Restrictions on access to these trade routes can disrupt the commerce within a state. This makes it all the more important to delve into the criticality of these routes and the political manoeuvring around them. From a Chinese perspective, it is a recall of its ancient strategic culture.

Modern Chinese defence policy traces its origin in Sun Tzu’s ‘Art of War’, which emphasises using psychological and strategic combat to expand territorial and political influence. In the last three decades, China has focused extensively on strategically advancing its position globally by using hard, soft and economic power. The hegemony of Beijing and its intentions can be analysed effectively through the String of Pearls theory.

The term ‘String of Pearls’ was coined by Booz Allen in 2005. In his report titled ‘Energy Futures in Asia’, he projected China’s expansion of its naval power in the Indian Ocean Region. The String of Pearls strategy emphasizes China’s economic, military, diplomatic and political stature in the region. (Ashraf, 2017, 169) Explicitly, this project reflects China’s geopolitical ambitions and diplomacy. However, its impact on India is implicit and intended. Every location or ‘pearl’ in this string has been strategically curated and cultured by China to serve these dual objectives. This paper will discuss each of these pearls, analysing their importance from a trade and geopolitical perspective alike.

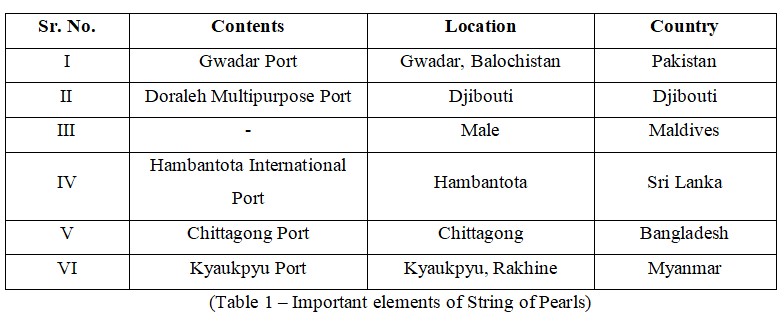

China’s active role in the Indian Ocean Region is apparent, with at least 17 projects in the region pointing to Beijing’s involvement. Out of these, 13 projects have seen direct Chinese involvement. (Faridi, 2021) Among the multiple speculated projects, this paper will focus on 6 such maritime projects, evaluating them based on the following criteria:

I. Chinese investment and involvement in the project

II. Geographical importance of the project

III. Potential threats to India due to the project

IV. India’s strategy to neutralize Chinese advances

Gwadar Port and CPEC

The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is a mere subset of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), that will be discussed later in this paper. CPEC Memorandum of Understanding was signed in 2015 with the Chinese government and banks pledging to infuse a fund of $45.6 Billion to Chinese companies for developing energy projects and infrastructure in Pakistan. (Khan & Khan, 2019, 70)

The deal also includes a mention of the Karakoram highway which passes through India’s Gilgit Baltistan – a region occupied by Pakistan. Gilgit Baltistan shares its border with Ladakh and Jammu and Kashmir which are parts of Indian-administrated Kashmir. Thus, incremental Chinese access to these regions through the highway is a matter of national security and sovereignty for India.

Politically and economically, one of the largest Chinese investments under CPEC has been for the Gwadar port. China has been affiliated with the project since 2002, having provided $248 Million for its construction. It is to be noted that the management of this port is granted to the Chinese Overseas Port Holding Company (COPHC) till February 2055. While both countries categorically deny speculations of using this port for military purposes, Takreem alleges that China is planning a naval base in this region. (Khan & Khan, 2019, 79)

The Gwadar port is geographically important as it is located at the junction of the Strait of Hormuz and the Arabian Sea. The Strait of Hormuz forms a chokepoint between the Arabian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman. One-third of Liquified Natural Gas and One-sixth of oil produced globally passes through this narrow strait which makes it an important trade route. China’s unchecked control over a strategically located deep seaport in this region gives it an advantage in controlling the fuel supplies to the Indian subcontinent. (Baabood, 2023)

India’s policy of neutralising this Chinese involvement includes adapting a similar mode of operation as used by China – investing in ports and other similar projects. Thus, to counter China’s advantage in the Gulf of Oman, India has been proactive in striking a deal with Iran. New Delhi and Tehran signed a Long-Term Main Contract in May 2024, awarding the India Port Global Limited (IPGL) a 10-year contract for the development of the Shahid Beheshti Port Terminal in Chabahar. This is also one of the India-Iran Flagship Projects. (Press Information Bureau, 2024)

Suez Canal, Djibouti and Oman

From the case of Gwadar and Chabahar ports, it is established that ports are not only acting as crucial commercial harbours but also as tools of geopolitical manoeuvring, military control and most importantly – controlling the trade waters. In the same context, the Suez Canal holds the utmost importance.

Suez Canal is responsible for about 12% of global trade, including about 30% of the world’s container traffic. It also acts as a route for about 7-10% of the world’s oil and 8% of Liquified natural gas trade. Also, the quickest sea route from Europe to Asia, it witnesses transit of goods amounting close to $1 Trillion annually. (The Importance of the Suez Canal to Global Trade - 18 April 2021, 2021)

The Suez Canal saw a temporary blockage starting on 28 March 2021. BBC News reported that German insurer Allianz analysed that the blockage could take the global trade to a deficit of $6-10 Billion a week and reduce annual trade growth by 0.2-0.4%. While this blockage was not intentional, it goes on to show how sabotaging trade on this route could affect economies worldwide. Thus, the possibility of any such Chinese action cannot be ruled out, given its alleged involvement in bloodless economic coups – destabilising a rival state’s economy or making it a subsidiary by engaging them in debt traps through its cheque diplomacy policy.

The premise for the same has already been set up by China’s investment in the Gulf of Aden. Beijing has successfully established cordial ties with Djibouti, which is a keen participant in China’s Belt and Road initiative. A Chinese company has already invested $350 Million to develop Port De Djibouti into a global commercial hub. Other Chinese investments have focused on intra-state transport including airports and railways. (Saxena et al., 2021)

It is a growing matter of concern as the Chinese modus operandi in Djibouti is similar to that in Pakistan – making a much smaller economy reliant on Beijing by facilitating irreversible investments in inter as well as intra-state infrastructure, thus making it a vassal state by orchestrating the breakdown of its economic sovereignty – a hallmark of China’s cheque diplomacy.

While India attempted to trump China in the case of Gwadar by its advancement in Chabahar port, any such possibility in the Gulf of Aden looks bleak. The pirate-friendly waters of south-bound Somalia and conflict-ridden Yemen to the north leave no credible alternatives for India. The best bet for New Delhi in the southern Indian Ocean is the Assumption Islands of Seychelles, which is still over 1800 kilometres away from the mouth of the Gulf of Aden that opens into the Indian Ocean. Back in Seychelles, the possibility of an Indian base stands on weak ground. Thus, India needs to recalibrate its approach against China in the context of the Suez Canal.

Pushing things south: Challenges in Maldives and Sri Lanka

The junction of the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean is a potential flashpoint in Indo-Sino relations. While both states have given significant importance to establishing their presence near the Gulf of Aden and Strait of Hormuz, any such activity will be futile should they fail to replicate the same in this junction. Even after bypassing Aden and Hormuz, trade shipments have to travel a long distance via the Strait of Malacca to reach the Chinese land. Meanwhile, the shipments bound for India’s eastern coast will have to pass through the proximity of its neighbouring states Maldives and Sri Lanka. At this juncture, the String of Pearls, which up until now would seem like a disjointed collection of diplomatic tactics starts taking shape, tightening itself around India. This has been possible due to China’s successful advances in these two states.

In Maldives, Mohamed Muizzu won the 2023 elections on the ‘India Out’ campaign and has turned in favour of China since the election to office. While Chinese ships, allegedly research vessels have been frequent to hit the shores of the island country, recent speculations state otherwise. It is alleged that China is secretly building a military base on Feydhoo Finolhu Island, which has been leased to China till 2066. Meanwhile, the island has also seen a massive increase in size to 1,00,000 sq. km., as opposed to the earlier 38,000 sq. km., coupled with rapid infrastructure development. (Srivastava, 2020)

About this, India has already tapped into its territory and waters. Indian Navy’s Naval Detachment Minicoy was commissioned as INS Jatayu. Before this, India had already commissioned INS Dweeprakshak in Kavaratti. India thus plans to secure its borders by installing its maritime forces at the neck of the ocean. (Press Release: Press Information Bureau, 2024)

Unlike Maldives, China’s intentions in Sri Lanka are an open secret. The biggest groundbreaking development in this sector was the deal of the Hambantota port, which was handed over to China in December 2017 on a 99-year lease. Along with this project, China is also actively involved in the development of another mega project, known as the Colombo Port City in the Sri Lankan capital, a large part of which has been leased out to a Chinese state-owned enterprise. (Tonchev, 2018, 1)

India has been swift to persuade Sri Lanka to balance out its priorities in handing over port contracts. The Adani Group of India signed a $700 Million deal with the Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA) in October 2021 to build a new terminal right next to a Chinese-run jetty in Colombo. Adani conglomerate’s Adani Green Energy is also planning to $442 Million to develop wind power stations in Pooneryn and Mannar. Sri Lanka also jointly awarded the contract for the management of Mattala Rajapaksa International Airport to India and Russia. Interestingly, this airport was built with Chinese funding. (Mushtaq, 2024)

Visibly, the Chinese advances threaten India’s security and trade opportunities on multiple fronts, every time China possibly gains ground (or water in this case) over India. China has always been early to establish its control in the sea while India has followed with a counterstrategy, which has been effective but inefficient. India’s approach has also involved chasing the Chinese route and making its presence felt near the Chinese establishments. However, as these trade routes move towards the east, we see a clear divergence. While China emphasized gaining strategic advances in Bangladesh and Myanmar, India made strategic moves in the Strait of Malacca, another key regional chokepoint, especially for Chinese trade.

The Bay of Conflict: Challenges in Bangladesh and Myanmar

China in addition to existing overseas naval bases has also invested in the Kyaukpyu Port in the Rakhine state of Myanmar, a deal worth $7.3 Billion wherein a Chinese company will build and manage this deep sea port for 50 years starting in 2016. Apart from its strategic location, the town is also a gateway for a flourishing oil pipeline worth $1.5 Billion and an additional pipeline running to China’s Yunnan province. (Poling, 2018, 5)

A favourable Sri Lanka with access to the Kyaukpyu Port in Myanmar solves a much larger problem for China – because it can then transport its oil and other shipments to China without passing through the Strait of Malacca, which has been a location of dispute and deadlock. In this regard, China has already financed the construction of an oil pipeline in Myanmar which connects to China and started operations in 2017. This pipeline reportedly can carry 22 million barrels of oil annually, which would then account for 6% of China’s yearlong oil demands as of 2016. (Poling, 2018, 5)

While a conflict lurks in the Bay of Bengal, Bangladesh naturally becomes an important player. Dhaka under the Sheikh Hasina regime had adopted a conciliatory, diplomatic approach in dealing with New Delhi and Beijing. Its approach towards leading the diplomatic negotiations in the case of the Chittagong port exemplifies the same.

China emphasized on infrastructure development in Bangladesh, overtaking India as its largest trade partner in 2015. A rumoured Chinese assistance worth $8.7 Billion for the development of the Chittagong port as a deep sea port dates as back as 2010. China also plans to develop the Dhaka-Chittagong High-Speed Railway and a 220-kilometre pipeline that would facilitate offloading of imported oil at the Chittagong refinery – instrumental for Chinese objectives. (Bose, 2022)

Conclusion: The road ahead for India

China’s systematic acquisition, control and militarisation of ports on foreign soil as discussed in this paper is merely a subset of China’s grand strategy of dominance in the subcontinent. In fact, the String of Pearls theory also does not give a complete picture of China’s strategy and its implications on trade and commerce.

Essentially, it can be deduced that all the major powers of the world and India were late in understanding this Chinese strategy and are left catching up. While India achieved a tactical victory by challenging China in the Strait of Malacca and strengthening its position using Singapore’s Changi Naval base, China’s policy of reducing its dependency on that chokepoint is also taking shape.

Additionally, China’s ambitious New Silk Road and Belt and Road Initiative, if and when completed, holds the potential to eliminate arm-twisting in the Indian Ocean Region, as it would gain access to the Global markets by road alone. This would leave India in a difficult position, given that the majority of trade is still carried out via water. On the other hand, India has actively rallied for the International North-South Transport Corridor, that would India to Russia via Iran and Central Asia. This, however, does not eliminate the possibility of the threats posed to India’s trade interests.

China has significant advancement in strategic locations at the Strait of Hormuz, Gulf of Aden and thus essentially the Suez Canal. Beijing’s further involvement in the maritime centres of India’s neighbouring countries like Sri Lanka, Maldives and Myanmar acts a significant threat to India’s National Security. Every such addition by China strengthens its ability to wage a multifront maritime war against India, not to mention the already existing border conflict in Ladakh, Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh. This, however, only covers the facets of an operative war. With this series of multiple projects, it also developed the ability to trap India in a geopolitical trade war, restricting its access to global trade routes.

This paper argued earlier that Bangladesh is one of the formidable allies for India with it attempting to balance out between Beijing and New Delhi. However, the ongoing political instability in Bangladesh has potentially hurt those dynamics. The Chief Advisor of the Interim Government of Bangladesh – Muhammad Yunus had cordial ties with Beijing much before he entered into the political spectrum. This also includes his role in establishing ‘Grameen China’ based on his ‘Grameen Bank’ model for which he won the Nobel Prize in 2006. On the other hand, with Sheikh Hasina’s exit from Bangladesh, there is a visible political vacuum in the state, which could be potentially filled by the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and its leader Khaleda Zia – which have resorted to anti-India rhetoric in the past.

In conclusion, India’s bilateral ties with China have a very significant impact on trade and commerce across the world, including but not restricted to its geopolitical implications and economic ramifications. Similar to the ‘String of Pearls’ theory, the intelligentsia has been keen on devising a ‘Necklace of Diamonds’ theory and a ‘Double Fishhook strategy’. However, without any substantial progress on those lines, these strategies shall remain merely on paper. Moving forward, New Delhi’s strategy in the sea would be essential in determining her security, sovereignty and the fate of her trade and commercial activities – as India plans to bolster itself on becoming a Global Manufacturing Hub with a $5 Trillion GDP and the world’s third-largest economy.

References

Amonson, M. K., & Egli, C. D. (2023, March - April). The Ambitious Dragon: Beijing’s Calculus for Invading Taiwan by 2030. Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs, 6(3), 37-53. https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/JIPA/Display/Article/3371474/the-ambitious-dragon-beijings-calculus-for-invading-taiwan-by-2030/

Ashraf, J. (2017, Winter). String of Pearls and China’s Emerging Strategic Culture. Strategic Studies, 37(4), 166-181. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48537578

Baabood, A. (2023, May 24). Why China Is Emerging as a Main Promoter of Stability in the Strait of Hormuz. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/res earch/2023/06/why-china-is-emerging-as-a-main-promoter-of-stability-in-the-strait-of-hormuz?lang=en¢er=middle-east

Bose, S. (2022, May 17). The Chittagong Port: Bangladesh’s trump card in its diplomacy of Balance. In Expert Speak - Raisina Debates. Observer Research Foundation. https://www.orfonline.org /expert-speak/bangladeshs-trump-card-in-its-diplomacy-of-balance

External Publicity Division Ministry of External Affairs Government Of India, www.meaindia.nic.in. (n.d.). Ministry of External Affairs. Retrieved June 19, 2024, from https://www. mea.gov.in/Uploads/PublicationDocs/191_panchsheel.pdf

Faridi, S. (2021, August 19). China's ports in the Indian Ocean. Gateway House. https://ww w.gatewayhouse.in/chinas-ports-in-the-indian-ocean-region/

Gokhale, V. (2022, December 13). A Historical Evaluation of China's India Policy: Lessons for India-China Relations. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/r esearch/2022/12/a-historical-evaluation-of-chinas-india-policy-lessons-for-india-china-relations?lang=en

The Importance of the Suez Canal to Global Trade - 18 April 2021. (2021, April 18). New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. https://www.mfat.govt.nz/en/trade/mfat-market-reports/the-importance-of-the-suez-canal-to-global-trade-18-april-2021

Khan, M. Z. U., & Khan, M. M. (2019, Summer). China-Pakistan Economic Corridor: Opportunities and Challenges. Strategic Studies, 39(2), 67-82. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48544300

Mushtaq, M. (2024, May 9). Sri Lanka turns to India as counterbalance to Chinese presence. Nikkei Asia. https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Sri-Lanka-turns-to-India-as-coun terbalance-to-Chinese-presence2

Press Information Bureau. (2024, May 13). PIB. https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePa ge.aspx?PRID=2020454

Press Release:Press Information Bureau. (2024, March 2). PIB. https://pib.gov.in/Press ReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2010884

Saxena, D. I., Dabaly, R. U., & Singh, A. (2021, August 4). China's Military and Economic Prowess in Djibouti. Defense.gov. https://media.defense.gov/2021/Nov/17/2002894852/-1/-1/1/JIPA%20-%20SAXENA%20-%20AFRICA.PDF

Srivastava, A. (2020, May 15). Chinese Military Base In The Indian Ocean Near Maldives To Complete 'String Of Pearls' Around India? EurAsian Times. https://www.eurasiantimes.com/chinese-military-base-in-the-indian-ocean-maldives/

Tonchev, P. (2018, April 1). Along the road: Sri Lanka’s tale of two ports. European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS), 4, 1-4. https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep2147